We know the city so well, we wrote a book about it. Be one of the first to see what it looks like here!

The word shipyard is synonymous with Gdańsk, due in the main to the social and political phenomenon that was Solidarity, the trade union movement which exploded out of the shipyard amid the strikes of 1980. Since then, the name Gdańsk for many has conjured up images of masses of striking workers led by a small man with a bushy moustache, while in the background hulked the giant cranes of the shipyard – the Lenin Shipyard. Well it appears that this shipyard is about to change forever and in doing so reflect changes, more than anywhere else in Gdańsk, that it helped bring about over 30 years earlier.

In the spring of 2013 plans were presented to the public showing the future of a large swath of the Gdańsk Shipyard. These plans, as we will see later, propose to revitalise this historic area and to re-connect it to the main city of Gdańsk a short distance away along the Motława River. The new development is to be called Młode Miasto (Young City) and while this name might look like the result of months of work by a high-powered PR agency’s image team, it in fact in recognition of the first organised settlement of the area over 600 years ago.

History – The Teutonic Young City

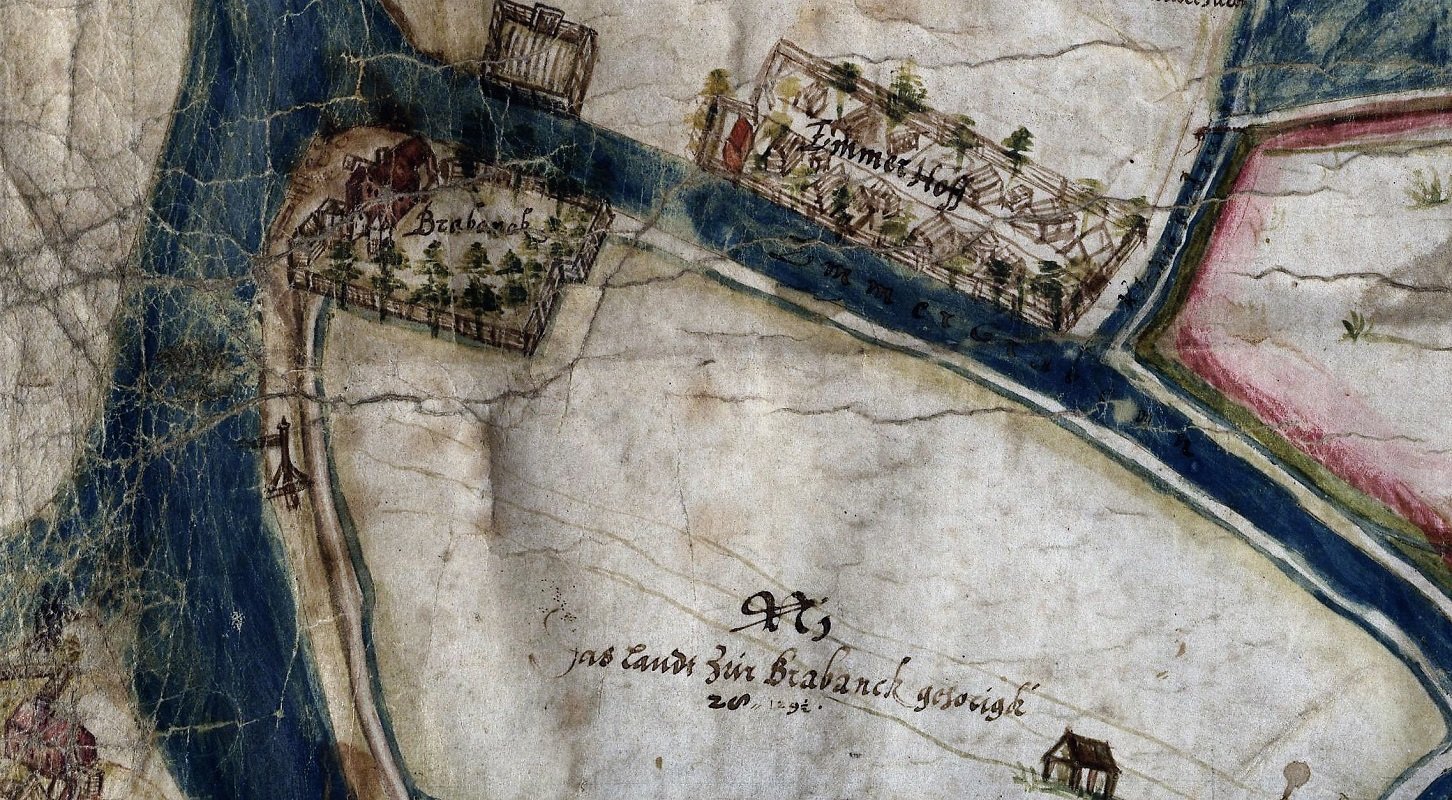

In the near 650-year history of activity and organised settlement on this site, shipbuilding is a relatively new industry here. The area first came to prominence in the times of the Teutonic Knights, who in 1380 developed an area to the north-east of the existing city of Gdańsk to create competition for the powerful Main Town and Old Town. Located at the point where the Motława River joins the Martwa Wisla (Dead Vistula) River, the Knights’ new district couldn’t be called New Town as this was an area already incorporated in the Main Town. They therefore settled on Jungstadt or Young City and began to develop an area which seems to have been close to where the European Solidarity Centre is found today. As they expanded their trade interests, the Knights expanded their settlement adding a market square, church, hospitals and a monastery. At the time in their history the Knights were probably at the height of their powers but things began to change when their enemies, the Poles and the Lithuanians formed an alliance in 1386 with the marriage of the Polish Queen Jadwiga and the Grand Duke Jogaila of Lithuania. Now as King Władysław II Jagiello of Poland, Jogaila set about putting previous differences with his cousin Vytautas to one side and building the force needed to drive the Knights out of their lands which stretched from Słupsk in the west all the way up to Estonia. Records dating from 1388 indicate that a ship repair yard in a locality called Brabank (where the Radunia Canal meets the Motława River) was in operation. This is the earliest-known link to a shipyard operation in Gdańsk.

This came to a head with the Battle of Grunwald (Battle of Tannenberg in German) in 1410. This defining battle in European history saw the joint Lithuanian-Polish force beat the Knights on the battlefield only to allow the remains of their army to fall back to their fortress city of Malbork. The Knights were broken however and over the following decades their influence and power deserted them. In 1455 King Kazimierz IV Jagiellonczyk ordered the liquidation of Jungstadt and the expulsion of the remaining Knights.

Napoleon to the Kaiser

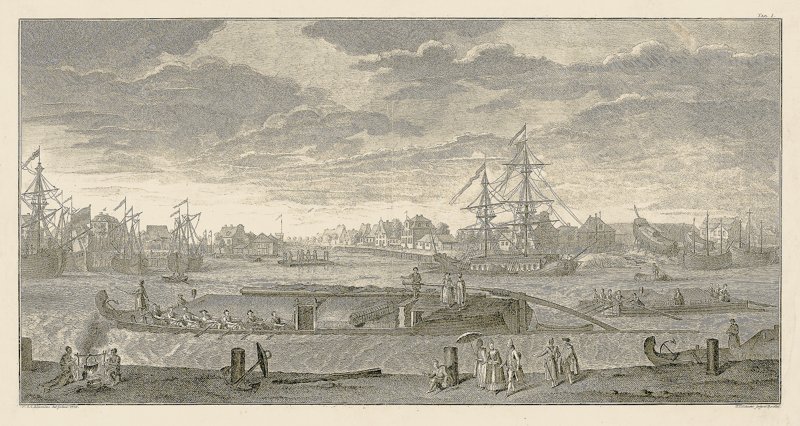

Now outside the city walls of Gdańsk, the area was used for growing timber and warehousing in the following centuries while also forming part of the city’s outer defensive ring with some fortifications built. Poland suffered partitioning by its powerful neighbours Hapsburg Austro-Hungary, Prussia and Russia in the last part of the 18th century and Gdańsk (now Danzig) found itself under Prussian control until 1807 when Napoleon’s army, containing Polish troops, marched east and took it. Napoleon saw Gdańsk as important in his overall strategy and in the same year created a free city state. The city’s fortifications were strengthened and this included new fortifications in Young City. The Free City was besieged by Prussians and Russians in 1813 and after the defeat of Napoleon, the city found itself back under Prussian control following the Congress of Vienna in 1815.

The Prussians set about improving their defences and in 1844 the Prussian government bought land around the site of Young City where they built a shipyard for their navy. This was named the Royal Shipyard Danzig (Königliche Werft Danzig) and though shipbuilding had a long tradition in the city this appears to be the point that shipbuilding on a large scale and on this land seems to have begun. Initially planned to be a place for the Prussian Navy to anchor and undergo repairs, very soon the Royal Shipyard was expanded to be able to produce vessels and the first was launched in 1853. Over the next two decades the Royal Shipyard produced a series of battleships and Danzig became a key player in the development of the Prussian Navy changing its name to the Imperial Shipyard (Kaiserliche Werft Danzig) following the creation of the German Empire in 1871. The years that followed saw investment in land, machinery and logistics to facilitate the building of more and bigger warships as Germany attempted to become a naval superpower. This was good news for the Imperial Shipyards which became the city’s largest employer and by the early part of the 20th century was estimated to be employing over 6,000 people.

The Boom Years

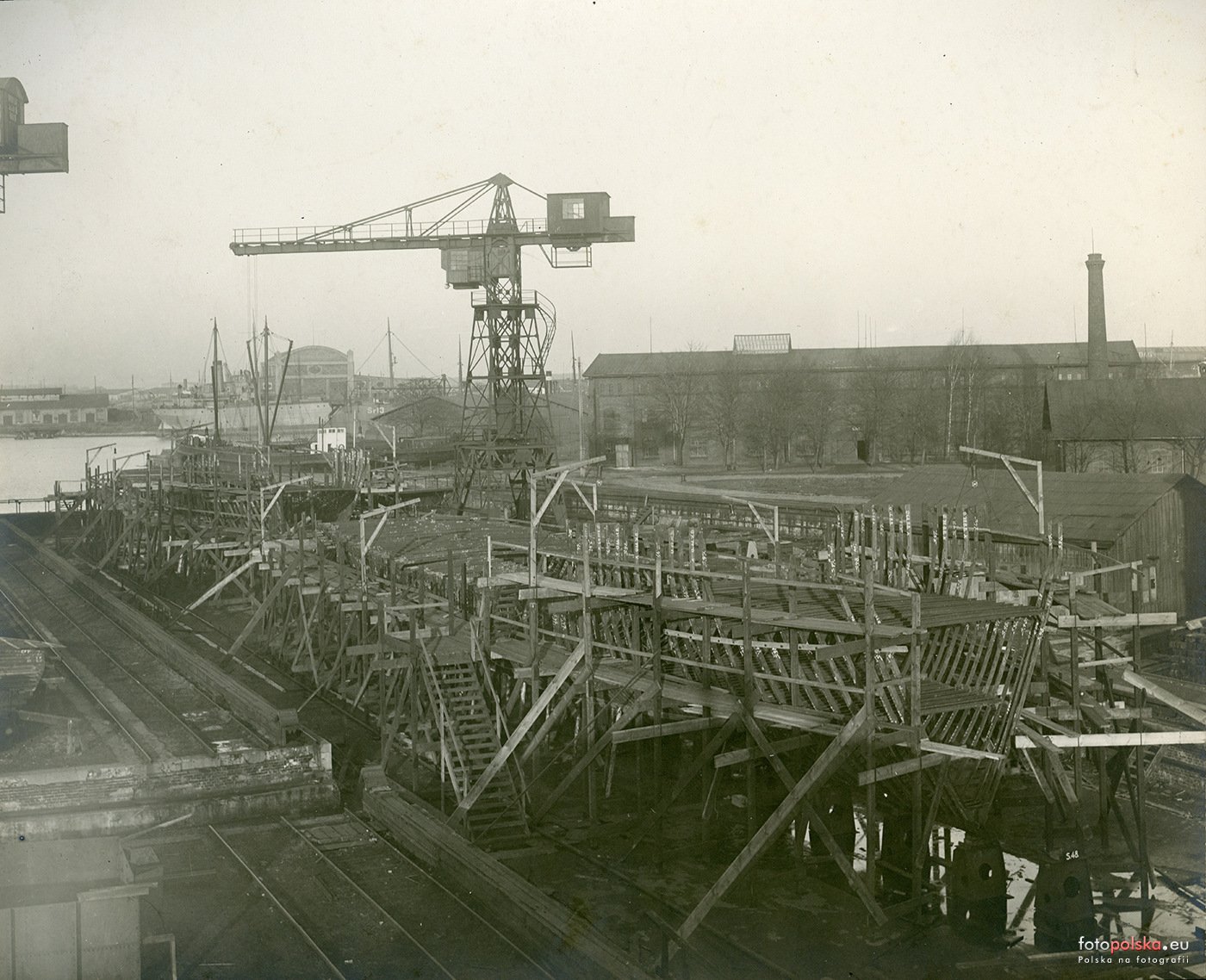

This boom in shipbuilding attracted a man called Ferdinand Schichau, a shipbuilder from the city of what is today Elbląg (Elbing) just to the southeast of Gdańsk. Schichau had also been benefiting from the determination of new German Emperor Wilhelm II to create a navy to match that of the British and spotted an opportunity to expand his operation in Danzig. Schichau negotiated to buy a tract of land and shoreline further along the Dead Vistula (Martwa Wisla), adjacent to the north of the Imperial Shipyard and work started in April 1890. The Navy insisted on authorising much of Schichau’s development but that was just part of his problems. The land he had taken on was wet and required a lot of work to make it suitable for building. But this didn’t hold Ferdinand Schichau back and he went ahead and built six slipways, the longest of which stretched over 200m. The intention was clear. Now that he had access to the sea Schichau was going to build big ships – cruise liners, heavy cruisers and battleships.

The first ship’s keel was laid in 1891 while construction of the yard was still going on and the orders continued to come pouring in. Ferdinand died in 1896 but his heirs found themselves at the head of a very profitable organisation which continued to build not just warships but large passenger vessels. The firm were innovative developing specialist vessels like dredgers and tankers. World War I saw production switched entirely to warships and Schichau again demonstrated their versatility by building submarines and interestingly beginning construction of the first giant Graf Spee.

Read our article on the Imperial Shipyard of Gdańsk | Self-guided Tourist Trail

The Bust Years

The end of WWI saw Danzig designated as a free city state and, most importantly for the Imperial and Schichau shipyards, a de-militarised zone. The Imperial Yard, as a German state asset, was possessed and liquidated while the Schichau yard found itself having to turn production away from military craft (the Graf Spee was scrapped). The 1920's saw strikes at the Schichau yard which drastically cut jobs and saw itself fall behind international competitors through a lack of investment in new equipment and technology. The Imperial Yard re-opened following the creation of the International Ship Building and Engineering Company Ltd by British, French, Polish and Danzig investors and the years until the Great Depression saw small vessels built the Schichau yard was forced to start offering cut-price repair work to survive. Eventually the Schichau yard was saved from collapse by the German government who created the F. Schichau GmbH company in 1929.The thirties saw it producing fishing vessels for the Russians, tugs for the British and dredgers for the Chinese, amongst others, but production was generally low. Times were tough for the two formerly successful shipyards.

World War II and the U-Boat

That was to change with war however. In 1939 Nazi Germany invaded Danzig and incorporated the city into the German Reich. No longer handcuffed by the League of Nations insistence that no military equipment could be manufactured in the city and now with the financial and strategic backing of Berlin, the two shipyards went back into military production. The Imperial Yard was officially taken over by the German state in August 1940 and became the Danziger Werft AG (Danzig Shipyard) while the Schichau Yard became a public company with a retired admiral at its head. Production turned to large scale U-Boat production and both yards first turned out type VIIC U-Boats with the Schichau Yard, aided by the forced labour of inmates of the nearby Stutthof Concentration camp, moving onto the new XXI-type later in the war. Danzig was a perfect location for both the building of vessels and the training of the crews that would sail them.

Roger Moorhouse, in his book 'Ship of Fate: The Story of the MV Wilhelm Gustloff', describes the scene:

The eastern Baltic Sea, safely beyond the range of most Allied aircraft, provided the perfect arena both for the construction of submarines and the schooling of submariners. Danzig, for instance, was home to two shipyards –the Danziger Werft and the Schichau –which were central to U-boat production, contributing over 150 of the 700 completed Type VII vessels that were the mainstay of the German wartime U-boat fleet. Nearby Gotenhafen, meanwhile, became home to two U-boat training flotillas –the 22nd and 27th –and was the base port of the two Unterseeboots-Lehrdivision (U-boat training division). The Wilhelm Gustloff served as the division’s floating barracks, home to around 1,000 cadets and staff.

Many legends are attached to this period including one which suggests a XXI-type U-Boat left Danzig in March 1945 with the Nazi research for the atom bomb destined for Japan. We’ve yet to find any proof of that but what is clear is that the Allies were very concerned with the production of more U-Boats designed to sink their ships. The area was bombed intensely and while it is commonly believed that Gdańsk suffered so much damage because of the Red Army shelling the city in 1945, it is actually the Allied bombers who caused the majority of the destruction that left Gdańsk a pile of rubble at the end of WWII.

When the Red Army did arrive in March 1945, they discovered the shells of many U-Boats still awaiting completion and while it is rumoured some ended up being shipped up the coast to the conquered city of Konigsberg (which became Kaliningrad, the home of the Soviet Baltic Fleet in the Cold War), some hulls were used in the shipyard for storage and for bunkers. The Red Army plundered the two shipyards, particularly the Schichau Yard, for anything they could lay their hands on. The authorities took control of the two yards renaming them Shipyard No. 1 (Danziger Werft) and Shipyard No. 2 (Schichau Yard) before merging them into one yard in October 1947 under the name Stocznia Gdańska (Gdansk Shipyard).

1945-1980

The shipyards, despite their pitiful state, were vital to post-war Gdańsk. While thousands of Germans had fled west away from the advancing Red Army, the years following the end of the war saw many more thousands of Poles flood into the city. Many had been forcibly moved from territories in the east which had been ceded to neighbouring countries while Poland had been given parts of former Germany effectively moving the whole country to the west. These refugees quickly needed shelter, food and work. Abandoned buildings which remained standing were taken over and new homes built. But aside from the reconstruction of the city, the shipyards offered the main source of employment. Along with shipyards 1 and 2, a third unsurprisingly named Shipyard No. 3 was built further along ul. Jana z Kolna. Production began again in the shipyards as early as July 1945 and the first vessel built by the new state-owned company was the Sołdek, an ore-collier for the Polish Steam Company which was launched on November 6, 1948. Today the Sołdek is maintained as a museum by the Maritime Museum, and located on the Motława River, close to the Crane.

The Gdańsk shipyard became the region’s largest employer and at one point was the direct place of work for nearly 20,000 people. Buses would ship workers in from all over Pomerania and they like workers in heavy industries all over the Soviet bloc, were highly valued by the communist regime. While not all workers enjoyed all the benefits available, many would be considered to have earned better than average wages for the time plus have had access to amongst other things an on-site hospital and sports and social facilities. In the years following the war the shipyard turned out hundreds of ships of various size and function mainly for the Russians. Shipyard No. 3 became the Northern Shipyard in 1950 while the Gdańsk Shipyard became the Lenin Shipyard in 1967.

There had been protests against the authorities, most famously in 1956, but it was the announcement of sharp price rises to essential goods by the Communist Party leader Władysław Gomułka in December 1970 that was to cause the protests that would end in deaths of workers and the birth of what was to become Solidarność (Solidarity).

Solidarity

Although Solidarity was officially christened in 1980, its roots can be traced some ten years earlier. Protesting against plunging living standards workers at the Lenin Shipyards and others in Gdynia, Elblag and Szczecin took to the streets, with the army promptly called in to intervene. Bloody clashes led to the deaths of 45 people, and ultimately forced Władysław Gomułka out of power. Replaced by Edward Gierek, his half-mad economic policies served to create an illusion of prosperity, as well as generating a flush of jobs in Gdansk’s Nowy Port area. But the memory of 1970 did not fade and Gdansk remained a ticking bomb for the authorities. With the seventies drawing to a close tensions started to rise again, with living standards falling and the economy in huge debt built on massive foreign loans.

This time the workers learned from the mistakes of 1970 and did not confront the authorities but instead locked themselves inside the shipyards. Three days later leaders representing workers from over 150 industrial plants met in the shipyards to hammer out 21 demands, including the legalisation of independent trade unions.

Days of tension followed, with tanks and armed units stationed menacingly outside the gates of the shipyards. On August 31 the government backed down, agreeing to meet the 21 demands - thereby marking the first peaceful victory over communism. A month later, on September 22, delegates from 36 regional unions met in Gdansk forming a coalition under the name of Solidarity. Lech Walesa, the unlikely hero of August, was elected as chairman. The next few months marked a golden period for the nation; some ten million people joined the Solidarity movement, and Poland enjoyed a freedom unknown for decades.

Riding the crest of a wave Solidarity continued to lobby for further reforms and free elections, infuriating the Kremlin. With Soviet invasion a looming threat the Polish President, General Wojciech Jaruzelski, declared a state of martial law on December 13, 1981, and tanks once again rolled through the streets. Though Solidarity was officially dissolved, and its leaders imprisoned, it continued to operate underground. When Father Jerzy Popiełuszko, Solidarity’s chaplain, was abducted and murdered by the secret police over a million people attended his funeral.

Renewed labour strikes and a faltering economy forced Jaruzelski into initiating talks with opposition figures in 1988, and the following year Solidarity was once again granted legal status. Participating in Poland’s first post-communist election the party swept to victory, with Wałęsa leading from the front. Lech Walesa became the first freely elected president of Poland in December 1990 and served until 1995 when he lost the following election to Aleksander Kwasniewski, a former communist.

In spite of overseeing Poland’s transition to a market economy, Solidarity gradually found their power being eroded by the emergence of fresher political parties. The 2000 elections for the Sejm (lower parliament) sounded the death knell for the party. Failing to even make the minimum vote to qualify for representation in parliament, the party which changed history found itself out of active politics. In recent years it has once again become the voice of protest as it campaigns against government policies such as job cuts and the raising of the pension age as Poland’s largest trade union.

The Present

The new reality of the post-communist world saw the shipyard converted into a joint stock company part owned by the state treasury and part by the employees. Increasingly difficult market conditions and the economic ‘shock therapy’ the country was facing to turn into a functioning capitalist system saw the new Stocznia Gdanska S.A. go bankrupt in 1997. It was bought the following year by the neighbouring Gdynia Shipyard who sold it to the state-owned Industrial Development Agency in 2006. During this time the shipyard moved away from its traditional home and onto the Ostrow Island on the opposite bank of the Dead Vistula (Martwa Wisla).Production was also diversified and along with ship building companies operating in the shipyards are involved with the manufacture of wind turbines, steel constructions and specialist boat building such as yachts. In addition another yard, Gdansk Remontowa, located further along the banks of the Martwa Wisla past the Northern Shipyard, has seen great success in recent years building, repairing and converting ships from all over the world.

In 2007 a Ukrainian enterprise, the Industrial Union of Donbas bought a majority share of the Stocznia Gdanska from the Industrial Development Agency but in June of 2013 it was reported that a supplier had filed a motion for bankruptcy against the Gdansk Shipyard. Meanwhile in 2012 legendary Polish film director Andrzej Wajda shot much of what is reported to be his final film Walesa in Gdansk Shipyard. Portraying the famous Solidarity leader before and during the strikes of 1980, Wajda organised for the Lenin Shipyard sign to be re-created which brought protests and vandalism from some who criticised him for bringing the sign back.

The Future - Young City Gdańsk

With the terrain of the historic Gdansk Shipyard largely derelict the local government invited developers to make proposals as to how the area could be revitalised. In April 2013, developer BPTO, who has owned 22 ha of the shipyard since 2007, announced its plans to build a combined residential, business, cultural and entertainment complex featuring offices, apartments, bars and restaurants, hotel and conference centre. The area would be reconnected to the main city of Gdansk by waterside walkways while the heritage of the area would be maintained with the renovation of some of the former industrial buildings and the restoration of three of the existing cranes. Neighbouring residential districts, some dating back to the time of the Schichau Shipyard, would be renovated and incorporated into the new development.While there is a long road ahead in turning these plans into reality, work is nearing completion on one of the biggest developments in the area of the shipyard - The European Solidarity Centre. Work is also well under way on creating the transport infrastructure needed for the new development and the Nowa Walowa road extension can also clearly be seen as it snakes its way into the shipyard. The road ahead is clearly a long one but the Gdansk Shipyard once again finds itself changing with the times and on its way back to being at the centre of life in the city.

In the meantime the shipyard is becoming more accessible with new roads being built and local entrepreneurs taking the opportunity to use some of the previously derelict buildings to develop galleries, bars and clubs. For a start you can take a wander around where you can find remains of the shipyards in its various guises from Schihau to Lenin; places of interest relating to both World War II and the Solidarity era plus an increasing number of entertainment venues. The name Mlode Miasto has for years represented an alternative group who have used the post-industrial buildings of the shipyard for concerts, art exhibitions and a club including Wydzial Remontowy, B90 and CSG. While you might not want to be creeping through a deserted industrial area at night in your best bib and tucker, you won't need to here where there is no dress code, just a determination to have fun.

Comments