Jugoton

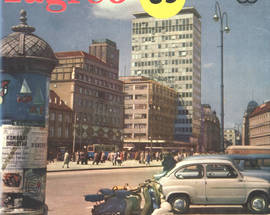

more than a year agoTwenty-five years after the fall of the Berlin Wall, the Cold-War divide still colours our perceptions of cultural history. People in Western Europe had all the sex, drugs and rock and roll; people in the East just gritted their teeth and carried on queuing for sausages. The former Yugoslavia, with its quasi-consumerist version of Communism-Lite, stood somewhere in the middle. But what if we re-drew the continent’s historical geography according to which countries had the biggest record industry, which countries underwent a punk-rock revolution in the late Seventies, or which countries produced the largest proportion of Eighties’ synthesizer bands? By any of these criteria, the Croatian capital Zagreb would have to be moved into the same camp as London, Manchester or Berlin; while large tracts of Mediterranean Europe would find suddenly themselves on the far side of the Urals.

Zagreb folk have long been aware that their city occupies an important niche in the history popular culture. It’s a status eloquently confirmed by East of Eden, an exhibition devoted to the former Yugoslavia’s largest record company, Zagreb-based Jugoton. Through a compelling array of LP sleeves and archive photographs, it reveals just how consumer culture, rock-and-roll rebellion and contemporary design combined to produce a thriving urban scene. It also shows how popular music served as a mirror of a changing society, and makes some attempt to answer the question of just why Yugoslav socialism could boast so much in the way of wop bam boom.

The latters’ long-standing fascination with the history of Jugoton is in part explained by the fact that they started out as record sleeve designers themselves. Their cover for the 1984 Dorian Gray album Sjaj u tami, with its mixture of home-grown new-wave energy and western pop aesthetics, is a typical episode in the Jugoton story.

Yugoslavia’s greatest ever record label began life as Elektroton in late Thirties, before being nationalized and renamed Jugoton in the aftermath of World War II. Its early releases were limited to traditional folk songs and Soviet-style revolutionary marching tunes, but changes on the international political scene soon had a profound impact on the Jugoton repertoire. With Yugoslavia thrown out of the Soviet bloc in 1948 and its leaders seeking a rapprochement with the west, popular culture took immediate advantage. The 1950s saw the rise of a new breed of domestic variety stars, notably Ivo Robić, who were deliberately styled on the western showbiz tradition. Indeed Robić reached number 13 on the US Billboard charts in 1959 with the song Morgen, proving that this cultural exchange was by no means a one-way affair.

Jugoton also began releasing western LPs under license, kicking off with the likes of Tommy Steele and Cliff Richard before taking the definitive plunge into western rock decadence with Elvis’s Golden Records in 1961. Releases by the Beatles and the Rolling Stones came in the years that followed.

In the early days at least, Jugoton’s releases by western bands were so popular that you would have to order them in advance and pay up front. As Sonja Bachrach-Krištofić remembers, customers would wait for the record shop to ring up and tell them when the disk actually arrived in stock. Very often the piece of plastic would be ready for collection before the sleeves had been printed – customers would have to go back to the shop to pick up the album cover later.

The Jugoton shop in central Zagreb (which still survives as the Croatia Records store on Bogovićeva) was itself a bold statement of westernization. Designed by architect Vjenceslav Richter, it was one of Croatia’s first examples of the shop-as-an-exhibition-space, combining minimalist interior and big street-facing windows to create the aura of a fashion boutique.

During the Seventies and Eighties the label served as the prime conduit for the flood of original music coming out of Croatia itself, and the name Jugoton became synonymous with Yugoslav pop culture at its most innovative and authentic. The fact that former Yugoslavia had the most vibrant punk and new wave scene east of the English Channel is often overlooked by western cultural historians, convinced that the communist-ruled half of Europe must have been a no-go zone when it came to safety pins and shredded jeans.

Zagreb punks Prljavo Kazalište released their first single on Jugoton in 1978, its grittily iconic cover photo taken by a young Mario Krištofić. Although Kazalište moved to Suzy Records to record their first album, it was Jugoton who handled the bulk of Yugoslavia’s burgeoning new wave, releasing albums by Zagreb bands Azra, Film and Haustor, alongside Belgrade’s Šarlo Akrobata and Električni Orgazam. It was an extraordinarily talented generation that left a long shadow; most Croats still know the songs of Azra frontman Johnny Stulić by heart; Haustor leader Darko Rundek remains an internationally-acclaimed songwriter and is regarded hereabouts as a national treasure. Synthipop duo Denis i Denis, and the New Romantic-inspired Dorian Gray, pointed Zagreb towards the dressed-up, post-punk Eighties.

Yugoslavia produced a veritable ocean of vinyl in the years between 1960 and 1990. Jugoton was merely the biggest of several powerful record labels, all of which were kept busy pressing the latest releases by western bands. This was in sharp contrast to other, more hardline, countries of Eastern Europe, where western rock and roll was administered in small, harmless doses. Yugoslav kids were able to go out and buy records by Bowie, Blondie, King Crimson, Kraftwerk, the Clash, U2, and many more. What did the Russians get in the 1980s? Uriah Heep.

Jugoton was renamed Croatia Records in 1992, and despite remaining one of the most powerful labels in the region, no longer commands the same mystique. The early Nineties also saw the decline of the vinyl LP and the rise of the CD. The last album produced by Jugoton’s vinyl pressing plant was a disc containing the sermons of Pope John Paul II, released in 1994. And if that’s the kind of record you simply can’t live without, you’ll probably find a near-mint copy in one of Zagreb’s second-hand shops.

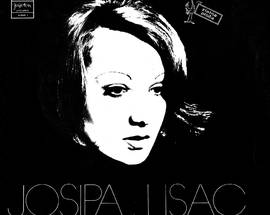

Five iconoc Jugoton album covers

Arsen Dedić Čovjek kao ja (1969) Design: Mihajlo Arsovski. The debut by easy-crooning poet and singer-songwriter Arsen Dedić is given a subtly psychedelic treatment by Arsovski, a prolific poster, magazine and book-cover designer.

Bijelo Dugme Kad bi’ bio bijelo dugme (1974). Design: Dragan S. Stefanović. The kind of politically incorrect album sleeve that would raise eyebrows nowadays, Stefanović’s sleeve defines the hard-rocking, hard-womanizing mythos surrounding this mega-popular Bosnian band.

Jazz Sextet Boško Petrović With Pain I Was Born (1977) Design: Boris Bućan. Contemporary artist Bućan styled this enigmatic cover, conveying both meditative simplicity and high art.

Various Artists. Svi Marš na Ples! (1980). Design: Mirko Ilić. The doyen of contemporary Croatian design, Ilić injected a punky, pop-art sense of fun into this New-Wave compilation album.

Dorian Gray Sjaj u tami (1984). Design: Bachrach & Krištofić. Dorian Gray were Croatia’s answer to David Bowie/Roxy Music-style art-school glam, an aesthetic eloquently summed up by this raw-but-romantic sleeve.

Jonathan Bousfield is the author of the Rough Guide to Croatia

Comments