Warsaw has existed for over 1000 years, and the millions of residents that have called the city home have all contributed to the character and history of the city as we know it today. Here are a few names and faces that you will see on numerous streets and monuments of Warsaw.

Syrenka

The origins of the name 'Warszawa', the Polish version of the capital's name, is steeped in mystery. While historians debate whether it is derived from the old Polish word for 'swamp' (warsz), fertile crop production (from the Polish word warzywa, meaning 'vegetables'), or a local tribal leader by the name of Warsz or Wars, locals tend to favour a more romanticised legend that city is named after a mermaid, or Syrenka, called Sawa. She is said to have made her way down the Vistula river from the Baltic and seduced a man called Warsz from his small fishing village (not to mention, the future Polish capital). Other versions say that she used her voice to warn the townsfolk of oncoming raids. Local hostilities was certainly the reason tiny Warszawa was fortified in the 12/13th century, and in the same era that the village gained city rights in the 14th century, Syrenka had become its coat of arms. Her symbolic role as the protector of the city is only too fitting, considering the number of times that Warsaw has had to stand its ground over the centuries. For this reason, Syrenka's mermaid likeness is portrayed bearing a shield and a sword! You can find her iconic statues in Warsaw's Old Town Market Square and on the Vistula Boulevards in the Powiśle district.

Jan III Sobieski

During one such battle in the defense of Warsaw in 1656, a future Polish king would distinguish himself while heroically leading a regiment of Tatar cavalry against the invading forces of the Swedish Empire. He would become known as Jan III Sobieski, and a string of other outstanding military performances would gain him enough popularity to ascend to the Polish throne in 1674. By that stage, the Polish royal court had relocated to Warsaw from Kraków in 1596, partially thanks to the city's growth in the 15th and 16th century.

Tadeusz Kościuszko

In the 18th century, political instability and corruption within the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth was taken advantage of by neighbouring Prussia, Austria and Russia. With its territories being gradually taken over (or 'partitioned') by these foreign powers, patriots such as Tadeusz Kościuszko were strongly in favour of constitutional reforms to maintain Polish sovereignty. Educated at Warsaw's Corps of Cadets in Kazimierz Palace (Krakowskie Przedmieście 26/28) and residing at Szeroki Dunaj 5 in the Old Town area, Kościuszko was devoted to the ideas of the enlightenment, and, after his first stint in Warsaw, he made a name for himself fighting in the Continental Army during the American War of Independence. After hostilities had ceased there, he saw a similar fight that needed to be waged in Poland. Thus, he rejected a comfortable life in the newly-formed United States of America to return back to Poland.

When the landmark constitution of May 3rd 1791 was signed in Warsaw's Royal Castle, Tsarist Russian forces mobilised in response. Kościuszko commanded a Polish division and was successful in holding back a numerically and technologically superior enemy. However, the odds were stacked against the Poles, and more territory would be partitioned in 1793. Kościuszko still had not given up on Polish sovereignty, and he used his national and military status to reform the Polish forces and engage the occupying forces. The 'Kościuszko Uprising' of 1794 culminated in the Battle of Praga in Warsaw's east, where its inhabitants were infamously massacred by the Russians. Following the surrender of Polish forces, the remaining territory of Poland-Lithuania was divided up a third and final time, completely erasing the country from the world map. Kościuszko was ultimately spared by the Russians, and would return to the newly-formed United States of America before living out the rest of his days in Switzerland. He died in 1817.

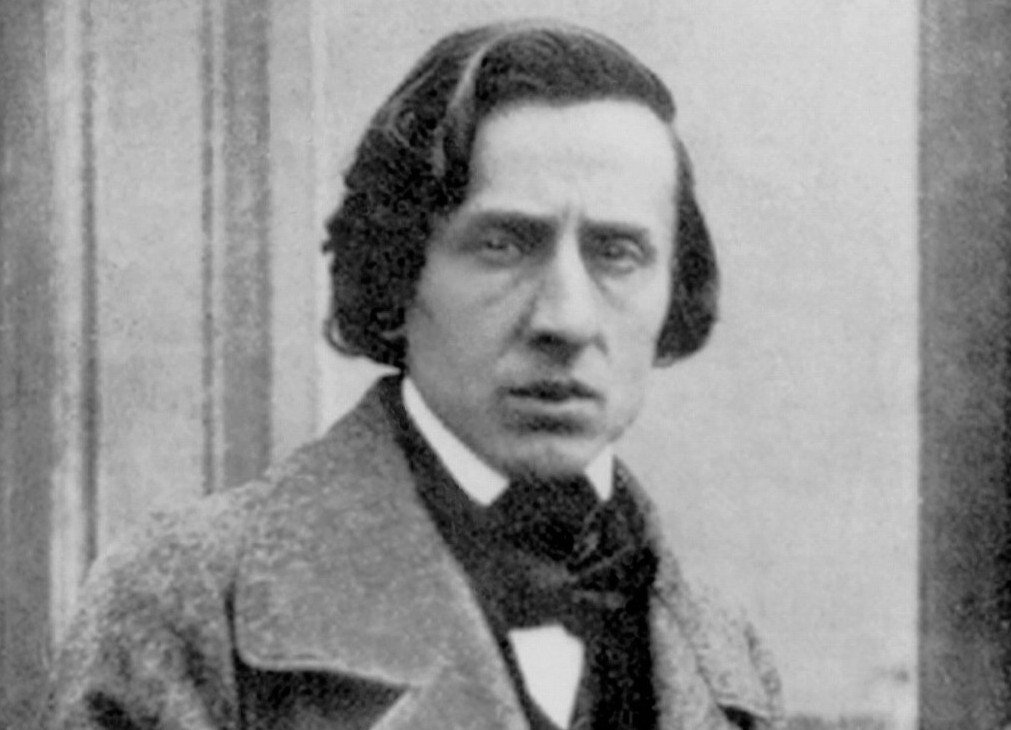

Fryderyk Chopin

In the 19th century, the Polish people living under foreign occupation would make numerous attempts to regain independence. Most notably in Warsaw, the 'November Uprising' of 1830 was brutally crushed, and saw many Poles flee their homeland in a period known as the 'Great Emigration'. One such individual who pursued a life abroad was Fryderyk Chopin, born in 1810 in Żelazowa Wola to a French father and a Polish mother. Years before the November Uprising, his family were teaching residents of the Warsaw Lyceum (later the Saxon Palace). Introduced to the piano by his mother, Chopin later continued his studies at the Warsaw Conservatory (now the Chopin University of Music) and, as a bonified child prodigy, he famously performed for Tsar Alexander I during his visit to the city in 1825.

Maria Skłodowska-Curie AKA Marie Cure

When Maria Skłodowska was born in 1867, Warsaw had been under Russian occupation for more than half a century. The use of the Polish language was forbidden, and women were not allowed to study at university. But Maria was the daughter of two teachers and fierce Polish patriots, and she was encouraged to receive an education in secret. Developing an interest in the sciences, her lack of academic prospects in Warsaw forced her to emigrate to Paris.

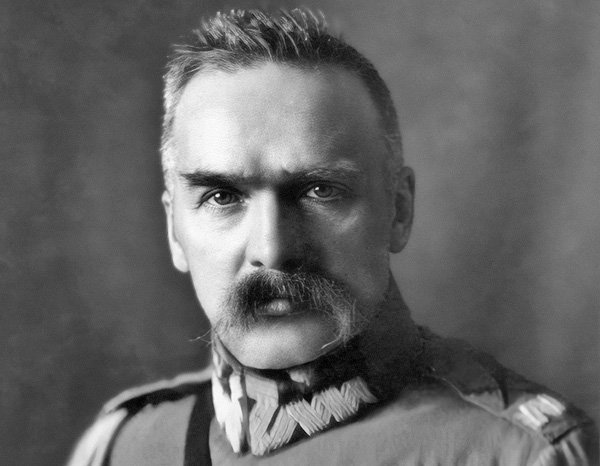

Józef Piłsudski

Another child of Polish patriots, Józef Piłsudski was born in 1867 in Zułów (now modern-day Lithuania), which was part of the Russian Empire at the time. Anti-Tsarist activities would have him imprisoned numerous times, and joined the Polish Socialist Party (PPS) in 1892 with an ulterior motive of achieving Polish independence. Piłsudski coordinated armed resistance against the Russian authorities in Warsaw and other occupied cities between 1904 and 1914. During WWI, he formed the Polish Legions within the Austro-Hungarian army to wage further war on Russia. The Bolshevik revolution would take Russia out of the conflict in 1917, and many elements of the Polish Legions would soon become the framework of a national Polish army, of which Piłsudski would command. After 123 of occupation, Poland finally reappeared on the world map in 1918, with Warsaw now as the official capital.

Independence would not come so easily, however, as Russia would march westward again in the hope of spreading the Communist revolution further into Europe. In August 1920, the outnumbered Polish army made its stand in and around Warsaw, well aware of what would happen if the capital fell to the Russians. However, good luck and determination combined with the brilliant strategy of Piłsudski and his officers saw the Battle of Warsaw repel the enemy in what is now known as Cud Nad Wisłą 'Miracle on the Vistula'. While Piłsudski also served as Chief of State until 1922, his retirement from politics was short-lived. He staged a military coup in 1926 in order to stabilise a fledging Polish government. In the century following his death in 1935, Piłsudski remains a controversial character in Polish history, though modern Poland would've looked much different without him!

Irena Sendler

When Poland was invaded by Nazi Germany in 1939, no one could have forseen just how extensive the Second World War would affect both Poland and its capital. Among other harrowing statistics, 85-90% of the city was completely destroyed, and some 700,000 of the Warsaw’s residents would be killed. Amongst the many tales of wartime bravery is that of Irena Sendler, Warsaw resident and catholic social worker who worked in the Warsaw Ghetto. When the Nazis began liquidating the area in 1942, sending its inhabitants to the death camps, Sendler became a key part of the Ghetto’s escape network, specifically helping to ferry Jewish children to safety. Transporting them in coffins, suitcases, sacks, and via Warsaw’s sewer system, Irena Sendler is credited with saving the lives of some 2,500 Jewish children.

These actions were not without risk, and, In October 1943, she was betrayed and arrested. Though subject to horrific torture – her legs were broken so badly she never walked properly again – she refused to divulge any names. She was sentenced to death, though a bribe from her accomplices allowed her to escape, after which she immediately returned to her work. After the war, Sendler set about reuniting the children she saved with their parents, even though most had perished in the Nazi death camps. In 1965, she was one of the first to be honoured by Yad Vashem, the Holocaust Martyrs’ and Heroes’ Remembrance Authority in Jerusalem (Due to post-war politics, she couldn’t collect the award until 1983. In 2003, she was awarded Poland’s highest honour, the Order of the White Eagle, and was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize in 2007. Irena Sendler passed away at age 98 in 2008. She is buried in Powążki Cemetery and the walkway in front of the POLIN Museum is named in her honour.

Comments