Phoenix from the flames

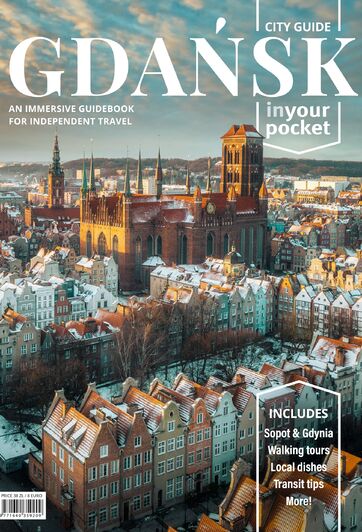

more than a year agoThe small matter of names to one side, what is popularly referred to as the old town is a quite remarkable place particularly when you consider that what looks like an ancient city borne of centuries of development was nothing more than a smoking pile of rubble in 1945 and in some places it is still being rebuilt today. The city’s story in terms of people as well as bricks and mortar is even more remarkable and a testament to the ability of ordinary people to overcome the most devastating setbacks. As covered elsewhere in these pages, many of the major cities in what is today Poland, paid a heavy price in WWII. The country lost over twenty percent of its pre-war population while millions found themselves strangers in their own land thanks to the decisions agreed at the Yalta Conference by Stalin, Roosevelt and Churchill. Pre-war Poland’s borders were moved westward by hundreds of kilometres in some places leaving the residents of cities like Wilno (today Lithuanian Vilnius), Lwow (Ukrainian Lviv) and Grodno (Belarusian Hrodna) forced out of their homes and off their land sometimes brutally.

But not only Poles found themselves being shunted westward – so did surviving Germans. Between World War I and World War II, Gdansk and the surrounding area had been the Free City of Danzig and for most of the previous 125 years part of Prussia and the German Empire. Even for the centuries prior to that when the city had been under Polish rule, it had been home to many ethnic Germans. The situation by 1945 was tragic – Danzig, unlike say Warsaw or Krakow, was seen as an enemy city by the British and American bombers, who did much of the damage and by the Red Army who then engulfed it from the east. The incorporation of Danzig into the Nazi Reich had been the event which effectively started World War II and by 1939 many of the local population had fervently supported Hitler. The collapse of Nazi Germany saw the city return to Polish control and overnight Danzig become Gdansk. Most ethnic Germans who had not been killed fled west by whatever means they could. The city officially fell on March 28 leaving Gdansk derelict and largely deserted. Remaining children cheerfully played with loaded anti-aircraft guns in the deserted Targ Weglowy while their neighbours waited nervously for the rear units of the Red Army to pour into the city and exact their revenge.

Conservative estimates suggest 90% of the city centre lay in total ruin, a nd if that sounds impossible to comprehend then just take a look at the pictures displayed in the Golden Gate at the top of ul. Dluga to get an idea of the Hiroshima style destruction. Only 38 houses in the whole of the city centre are reputed to have survived the siege, with debris mounted up to the height of several metres.

In fact, such was the ferocity of the Soviet advance that fires in the old town were blazing a month after the fighting had ceased. The indefatigable St Mary’s Basilica, a defining mark on Gdansk’s skyline, burned so fiercely that reports claim the bricks and bells in the tower melted, while the granary buildings on Granary Island (Wyspa Spichrzow) took an even harder hit; the inferno there continuing to burn until well into autumn. The material and economic cost was immense, the human cost incalculable. The pre-war population had stood at 400,000, of which 16,000 were registered to be of Polish descent. By the time hostilities ceased that figure was 124,000, of which only approximately 3,200 were Polish. How many of the pre-war population died and how many fled is impossible to compute, but either way Gdansk was a shattered shell of its former self. Reprisals against the remaining German population went unchecked, with murder and theft de rigueur by some drunken bands of Soviet soldiers. But it was rape that was to become the most virulent problem. It’s estimated that two million German women were violated by Red Army troops and the local Danzigers fared worse than most. Having been terrorized at night, the surviving Germans were expected to work next day. On April 25 the Mayor of Gdansk decreed all Germans report for rubble clearing duties every day at 7am. It was backbreaking work, and not without its grisly diversions; six thousand bodies were cleared under the detritus in April alone. But this was only to be a short term measure; verification panels were set up to interview individual German citizens to determine if they could stay in the city of their birth. These were essentially pre-determined kangaroo courts, and within a matter of years all traces of the German population had gone.

The place of the exiled Germans was filled by those Polish refugees, that had been displaced from the eastern territories that now came under Lithuanian, Belarusian and Ukrainian control. And it was these displaced Poles, as well as the surviving local Polish and Kashubian communities, that rebuilt the city and made it their own.

It’s amazing to think that the Gdansk you see today came within a fine hair of being turned into a grey, concrete forest; the city was being swamped with settlers, and understandably the priority was not to honour history and aesthetic values, but to provide these war weary pioneers with a roof. With people living in squalid, overcrowded conditions it wasn’t long until some began to campaign for a plan which would have seen St Mary’s rebuilt, but the rest of the area surrounded by the Orwellian style blocks you’d nowadays find in Warsaw. Not only was this master plan practical, it also gained support from the patriotic lobby. The argument was straight forward – the Poles didn’t want to rebuild the German city of Danzig. They wanted a new city, one that was indisputably Polish. No-one captured the spirit of this movement more eloquently than Edmund Osmiańczyk, and his fire and brimstone words made it into an issue of the influential Odrodzenie: “We are not going to cry over ashes, we won’t rebuild these reminders of the Teutonic Knights and the power they once wielded. We don’t want to remember. We will build in the Polish style, not that of the Teutonic invaders”.

Unfortunately, this Polish style they spoke of verged on the moronic. Plans that were floated included the construction of a skyscraper between ul. Korzenna and ul. Podwale Grodzkie, as well as a large four storey, 125 metre long concrete carbuncle by the train station (this design, devil be damned, was partially realized). Heated discussion continued over the next couple of years, but nothing was agreed and the job of clearing the city clanked on in the background. Efforts to tidy the town were doubled in 1947, and over 300,000 cubic metres of rubble were cleared in that year – some of which would be used in the production of breezeblocks, the rest dumped unceremoniously in Gdansk’s 48 pre-war cemeteries. Indeed, the organization of the clean-up operation was a fiasco. Chaos reigned, accidents were frequent, and worse still for the workers, bodies were still showing up everywhere – 1948 brought with it the discovery of a particularly nasty mass grave, that of 40 women buried between the Covered Market and St. Nicholas Church.

However, the year also brought with it the long overdue decision with what to do with downtown Gdańsk. The rebuilding commission chose to reconstruct six of the central streets that now form the meat and bones of the old town - ulica Długa, Ogarna, Chlebnicka, Mariacka, Św. Ducha and the Motława Embankment. However, even this was a compromise.

While the structures that sprang up here suggest the buildings were rebuilt to the last detail, that is in actual fact a fallacy. The majority are in effect little more than socialist, utilitarian blocks that have been graced with fancy townhouse facades. Either way, ultimately two major aims were reached: the construction of quick, suitable housing, and the construction of a quarter that retained the atmosphere of a historic town centre. It’s interesting to note that architects did use some semblance of artistic license. Reconstructed burgher houses once adorned with German motifs and mottos were given a Polish language makeover, while historic buildings that hadn’t been alive for hundreds of years were resurrected from the grave, and built once more to the designs detailed in recovered manuscripts and aging watercolours. By the same mark other buildings inexorably linked to German rule were condemned to memory; one such structure was the Danziger Hof on what is now Wały Jagielońskie.

Designed by Karol Gause of Berlin this neo-renaissance masterpiece survives only in postcards, and a damn shame too. Built between 1896 and 1898 the 120-room hotel was the most prestigious in town, its quarters hosting the Tsaristprince Alexei, members of the Vanderbilt dynasty, Kaiser Wilhelm II and even the regional HQ of the British & Polish Trade Bank.But history is a funny animal, and don’t bet on never seeing it again. The reconstruction of Gdansk has continued since that time with large parts of the waterfront only being rebuilt in the 70s and 80s. Even now empty plots can still be seen all over the city, while Granary Island is a permanent reminder of the destruction that was caused. But the city was brought back to life in those post-war years and it’s difficult to guess as you walk along the old town streets that anything so devastating could ever have befallen the city and many of those who now call it home

Comments