If you live in one of the major English-speaking nations of the world, especially if you're in the UK, there's an extremely high chance that you know at least one person with Polish heritage. Whether it's super obvious, like an accent, a surname ending in -ski or -ska, or something that comes up in conversation about World War II or family cooking, it's all part of a fascinating legacy that stretches across the globe from Australia to South Africa and even in obscure locations like Azerbaijan and Brazil. In many ways, it's Polonia - the Polish diaspora, and the idea that 'Poland Is Not Yet Lost, So Long As We Still Live' that has kept the nation-state together at times when things were looking dire!

But 200 years ago, the European magnet for Polonia was not the United Kingdom, as it has been thus far in the 21st Century. In the 19th century, Poles were big on making the move to France! There are many reasons for this. France and the Polish-Lithuanian commonwealth had close ties with each other since the 16th century and there was even a French king of Poland at one stage! France has always been a champion of democracy since its revolution in the late-18th century - around the same time that Poland was being partitioned. In fact, the cause of Polish independence was something that Napoleon was able to use to his advantage; sharing common enemies, he created the short-lived Duchy of Warsaw between 1807 and 1815 and Polish troops served in French Grand Armée in the Russian Campaign. Following the failed November Uprising of 1830, the Polish Government in Exile set-up in the Hôtel Lambert in Paris, one of the first most notable moves during the period known as 'The Great Emigration'. It was in France that these individuals would become the greatest ambassadors that Poland has ever had, aside from their individual achievements in science, technology, literature and music that have since had a lasting impact on the world.

Composer and pianist Fryderyk Chopin moved to France around the time of the November Uprising of 1830. Drawing on his Polish upbringing, the 1830s saw Chopin enjoy an impressively productive spell, composing a series of acclaimed polonaises and mazurkas. Today, Chopin is synonymous with the piano and unforgettable themes such as 'the Funeral March' are synonymous with death, which is exactly what happened to Chopin at the young age of 39!

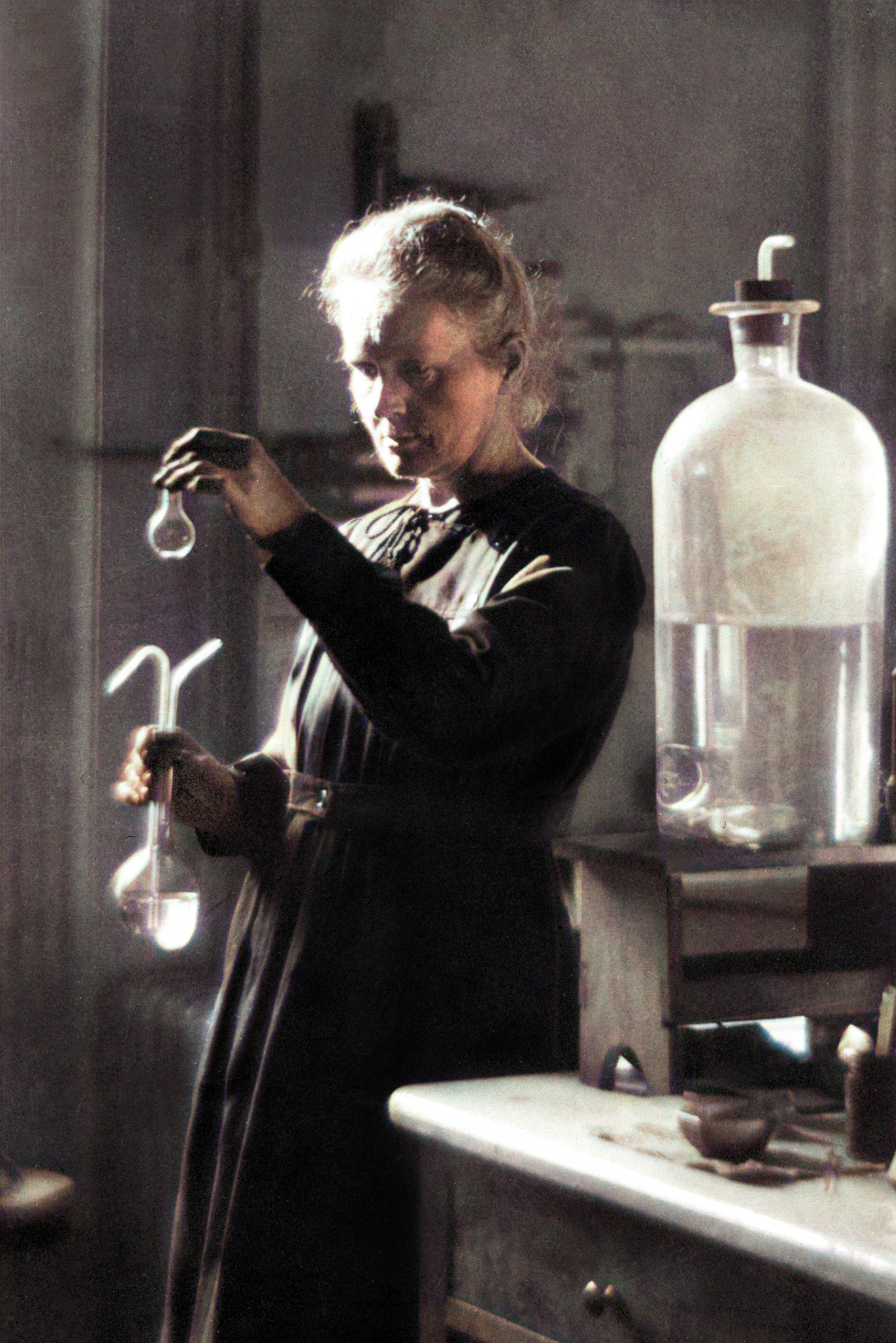

The parents of Maria Skłodowska had been involved in the January Uprising of 1863–65, and lost all of their property and fortune as a result. Skłodowska would also seek out a better life in France, as well as a career in science where she conducted pioneering research in radioactivity. She was married to Pierre Curie, giving her the more widely known French version of her name: Marie Curie. Skłodowska-Curie was such a patriot that she named the radioactive element, Polonium, after her homeland!

The story of Józef Korzeniowski's family is quite similar. Growing up in the Russian Partition of Poland, his father was jailed for being an active revolutionary. With the family fortunes effectively confiscated, he was taken on by his uncle at the request of his mother, who would end up sending him to Marseilles, France to become a merchant marine. Later pursuing a career as a writer in the English language, he is better known by his anglicised name: Joseph Conrad.

Poet Adam Mickiewicz was a member of a Polish independence society whilst studying at the University of Vilnius in the early 19th century. He was arrested by Russian secret police and exiled to central Russia. He would spend time in St. Petersburg and Moscow until 1829 when he began travelling abroad in Western Europe. Settling in Paris around the time that the November Uprising was in full-swing, the event would inspire his most famous work 'Pan Tadeusz'. He is considered one of the three national bards of Poland.

Another one of the national bards, Juliusz Słowacki, worked briefly for the government of the Kingdom of Poland and was a courier for the Polish revolutionary government during the November Uprising. He was sent to Dresden just before the rebellion was officially declared a flop and ultimately made his way to France as a political refugee. He was based in Paris for a good part of his life and literary career and saw himself in competition with Mickiewicz, who he felt was hogging the literary limelight. Amongst his patriotic works, he published Kordian, a romantic drama, illustrating the soul-searching of the Polish people in the aftermath of the failed insurrection.

A lesser-known name on the list, Jan Józef Baranowski, was a bank employee as a young man before the November Uprising of 1830 went down. He took up arms with his fellow Poles, however, upon the failure of the rebellion, he was arrested and thrown in jail for a number of years. Once he got free, he moved to France where he began working for the French railway as an accountant. But he saw that things needed improving and could be done more efficiently. Among his inventions was the ticket printing machine, the ticket stamping machine and the very first railway signalling device. Outside of the railway industry, he also produced the first vote-counting machine and an early version of the gas meter!

Read our article on the Top 10 Polish Inventions!

Comments