Unlike many of his contemporaries, Bronowski believed in bringing knowledge of the most complicated science to the masses, something he achieved via a remarkable gift of making the complex appear infinitely simple. That was his gift. Michael Parkinson - who interviewed Bronowski in 1973 - would later recall that the meeting had been perhaps the most rewarding and fascinating of his long career.

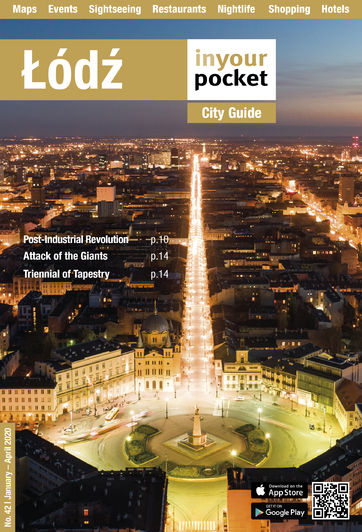

Bronowski - whose friends called him Bruno - finds himself the subject of a major feature in this guide because the man was born right here, in Łódź - then part of the Russian Empire - in 1908. His family were comfortably wealthy haberdashery traders, and his father travelled frequently to England. When the First World War broke out Bronowski’s family ironically fled first to Germany, before settling in England only in 1920. Speaking no English he was nevertheless given a place at the Central Foundation School in London, after which he won a scholarship to Jesus College, Cambridge.

While mathematics was his first love, Bronowski was drawn towards poetry in his early years at Cambridge, and it was while here that he began editing a poetry journal, Experiment. He wrote poetry too, and a promising career beckoned. Yet in the end - though he wrote poetry (when he had the time) until shortly before his death - Bronowski remained faithful to mathematics, staying on at Jesus College until 1935, when he took his doctorate in geometry. Like many idealists of the era Bronowski - who had spent time in Majorca during previous summers - was fascinated by the Spanish Civil War, but never volunteered. He did publish poetry on the subject, however, at war’s end in 1939. By this time he had become an English citizen, and was a research fellow at University College, Hull. He married in 1941, and was called up in 1942, spending most of the war as a researcher, with specific interest in the economic effects of bombing, applying theoretical mathematics to real situations. It was while still serving in the army - late in 1945 - that he visited Hiroshima and Nagasaki, a trip that would mark him for life.

On leaving military service Bronowski joined the National Coal Board as Director of Research, but his experience in Japan had begun to already lead him away from pure statistics towards human biology: specifically, the nature of violence and the relationship between science and dogma. His first major book, The Common Sense of Science, published in 1951, argued that art and science were not incompatible, going as far as to suggest that humanity could not prosper if they were. ‘The human race is not divided into thinkers and feelers,’ Bronowski wrote, ‘and would not long survive the division.'

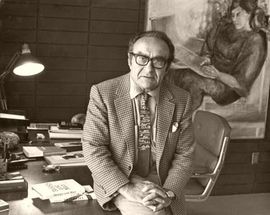

Increasingly high in profile, Bronowksi became one of Britain’s most famous - and popular - scientists thanks not only to his books but to his appearances on the BBC’s radio - and later television - programme The Brain’s Trust. Unashamedly intellectual, the programme’s huge following nevertheless demonstrated that ordinary people could grasp complex matters as easily as university professors, and that there was a public appetite for educational television. Bronowski’s engaging personality was in no small part responsible for the show’s success. His own series, Insight, in which he interviewed leading scientists and investigated the human capacity for knowledge, quickly followed, and was well recieved.

Bronowski’s academic home in the sixties was the Salk Institute for Biological Studies in San Diego, California, an institute of which Jacob Salk - who discovered the cure for polio - was head and Bronowski it’s Director of Biology. After joining the institute full time in 1964 Bronowski was able to devote himself to the study of the biological inheritance of human beings and - specifically - what made them unique. Using the institute as his incubator he toured the world giving a number of lectures based on his findings, and in 1965 a book appeared: The Identity of Man, in which Bronowski argued that not knowledge itself made man, but its pursuit. ‘Science would come to a standstill if every ambiguity were resolved,’ he wrote.

The Ascent of Man

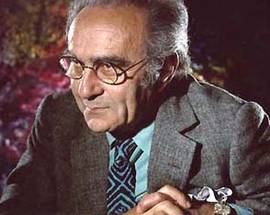

When the BBC wanted to make a scientific counterpart to its Civilisations series which looked at western art, it was the charismatic and familiar Bronowski they approached to do so. His good friend David Attenborough was at the time the BBC’s Director of Television. Initially reluctant - he was unwilling to stop work on research projects he had only just started at the Salk Institute - Bronowski’s desire to bring science to as wide an audience as possible persuaded him to take on the mammoth task. He took a sabbatical from the Salk Institute, and spent the next three years writing and making the The Ascent of Man, which was finally completed late in 1972. Bronowski travelled the world to make the programme, from Easter Island to Auschwitz, the scene of its most poignant and remarkable scene, still one of the most powerful images ever broadcast on television. Explaining how not science but dogma had killed four million people, Bronowski walks into one of the ponds were the ashes of those killed had been dumped and says: ‘We have to cure ourselves of the itch for absolute knowledge and power. We have to close the distance between the push-button order and the human act. We have to touch people.’ At that moment he reaches down and picks up a lump of ash. It is all the more poignant for knowing that large numbers of Bronowski’s Polish relatives (he was a Polish Jew) had been killed at Auschwitz.

A year later, on the Parkinson programme, Bronowski said something equally remarkable:

‘You see, the most awful thing about Auschwitz was that you realised that the people who'd been killed in the gas ovens, they were just dead, they were the fortunate ones. But the people who had shoved another lot of people into the gas ovens the next day - they were characters out of Dante's Inferno, living in endless Hell, because they'd lost all sense of human feeling and were going to repeat tomorrow the unutterable bestiality that they had practised today.’

Broadcast to widespread public and critical acclaim, The Ascent of Man was to be Bronowski’s last major project. He died at the age of 66, in 1974, of a heart attack, shortly after Ascent had first been broadcast. He is buried at Highgate Cemetery in London.

Epilogue

Some 30 years after his death, Bronowski’s daughter, Lisa Jardine - herself an academic of some renown - discovered a load of top secret documents in his study outlining the work he had done for the Allies during the war. As she discovered, her father had used his mathematical skills to develop bombing patterns to maximise death and destruction. He seemed to have issues reconciling his work with what the Nazis had done to members of his own family in Auschwitz: here, it seems, lay the genesis of that moving scene in Ascent, perhaps even of Ascent itself. Living in an era where science was blamed for the tragedies of the time - and was similarly seen as holding both the keys to a brighter future and to future tragedies - it could be argued that Bronowski wanted to demonstrate, particularly with The Ascent of Man, that the pursuit of scientific knowledge and science itself had been a positive thing for the human race and the reason why humans had made such advances. This is what made him such a remarkable Łódz man.

Bronowski’s legacy is therefore twofold. First there is his pure scientific legacy: the work, the theories, the scientific findings and the writings - as well as his poetry; then there is the popular legacy: the notion that science is not the sole property of the intellectual. That science belongs to man as a whole and that everyone is wired to understand it. That there is so much science on television now is something Bronowski contributed to and something of which he would approve. That it has been dumbed down to such a trite level however is something that would not have pleased him.

Comments