Born and bred in Joburg, Gerard Bester is a performer, theatre-maker, art instigator, and teacher with a long history in the dramatic arts. He's also a clown – of the classically French-trained variety, mind you. Equally passionate on and off stage, Bester has an impressive résumé: he was creative director of the Hillbrow Theatre, and has worked with the Soweto Youth Drama Society and Moving into Dance, to name but a few. In 2022, he took up the mantle as head of the Windybrow Arts Centre – a heritage house in Hillbrow dating back to 1896 that's now under the stewardship of the Market Theatre Foundation.

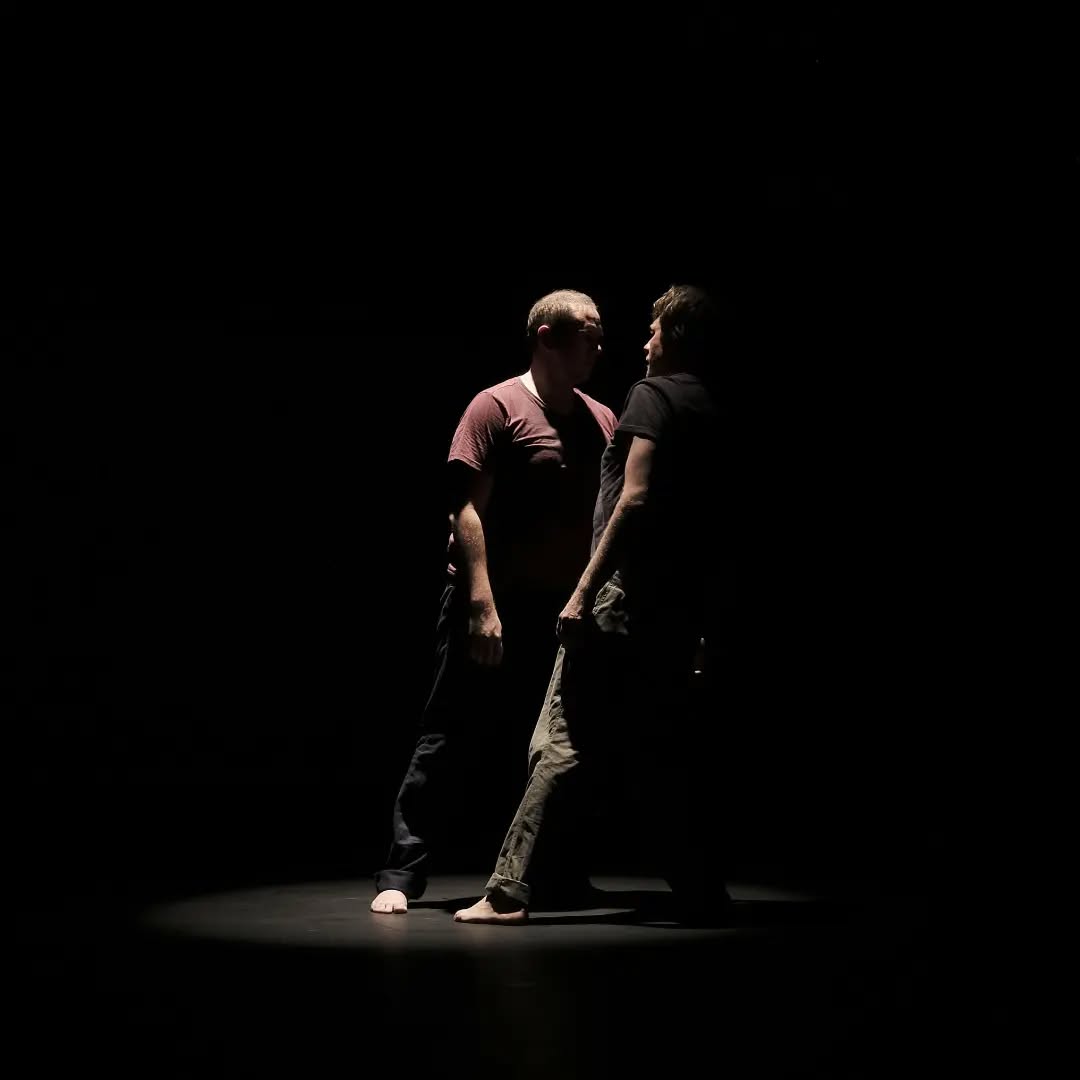

The renowned creatives Bester has collaborated with include composer Nhlanhla Mahlangu, dancers Gregory Maqoma and Athena Mazarakis, and actor Tony Miyambo. Among the awards he's won are a Naledi Award for Best Comedy Performance in 2007 and the STAND Foundation Mohlopi Award in 2024. Beyond this, Bester has certainly found himself in some interesting scenarios over the years. His bio gives us a few snapshots from his colourful life: "He has been seen in the water features of the Louvre in Paris, found hanging from the ceiling in his underwear at the Edinburgh Festival, and has danced naked in a warehouse in Newtown."

Behind the comedy and quirk, however, lies a deep desire to use the arts to transform society. As reviewer Sarah Roberson writes in a review of Bester's play, Sometimes I Have To Lean In, "It's all fun and games until we have to lean in and face the ugly truth." For Bester, the ugly truth is counteracted by the ability of the youth to improvise, and to find inspiration not just in the mundane, but in decay itself. Looking at Joburg through his eyes, we see the potential that lies in destruction, the beauty in ugliness, the safety in danger – and the indispensable job of the clown to bring awe and wonderment back to a world facing an existential crisis.

As far as places go, Bester's connection to Hillbrow runs deep: it was his place of birth, has been the site of many of his professional pursuits, and remains his favourite part of the city. Nearby Yeoville is where he met his husband, saying, "Our eyes met at the Peace March on November 30, 1995." (Read the story he shared with us for our #ValentinesInYourPocket series in 2024, along with other Joburg love tales, here.)

We spoke to Bester about being a student at the University of the Witwatersrand (Wits) in the 1980s, paving the way for Hillbrow's golden era, and the life of a reluctant anti-hero.

"To learn Joburg is to engage multiple stories and histories – nothing is entirely what it seems."

What drew you to drama, dance, and the world of theatre at large?

Ironically for an atheist, it was Godspell, an American musical version of the Passion Play. My uncle, Des Lindberg, played Judas and came through the audience singing a funeral song, carrying the body of Jesus he had just betrayed. Seeing someone close to me transform into 'the betrayer' shook up my concept of identity, self, and the possibility of performance.

My second revelation was seeing Tossie van Tonder in a solo dance work at my aunt and uncle’s soirée evenings on the Houghton Ridge. I was imprinted by the power of the expressive visceral body and the capacity of voice – through breath and guttural sounds – to communicate to an audience. Another memory is performing at the age of seven at The Nunnery at the University of the Witwatersrand in Clara Taub’s production of The Circus Boy. I knew instinctively that this was a world I wanted to be part of.

What were your student days at Wits like?

Wits was the first time stepping out of the white bubble that apartheid enforced and encountered a diversity of other races. I was hearing stories first-hand; narratives of diverse living conditions and the brutality of the apartheid state to black bodies. I had friends who would encounter necklacings on their way to university. This was the 80s and the education I received at university was as much about academia as it was about understanding the political conditions of daily life in our city.

University was also where I first started improvising and realised my unique ability to respond to audiences in the moment, and let those responses inform and form the work. It’s about a willingness to embrace vulnerability but also actively engaging in the act of listening, and the politics of listening and speaking. This fed directly into my interest in clowning but also in precarious inner-city neighbourhoods, where improvisation is daily life. I remember one lecturer saying in my third year that I had perfected the post-modern anti-hero role. And maybe that’s still the best description of me: a lifelong, sometimes reluctant anti-hero.

Clowning forms part of your professional repertoire – we've heard it said that clowns are their own breed. How does this medium speak to you?

The clown emerges out of a dark existential crisis and sees the world with awe and wonderment. There is no certainty in the world, and it is through play and laughter that we sometimes find meaning.

"In Johannesburg, sometimes the ugly is beautiful and the beautiful is ugly."

Some would argue the 'golden days' of Hillbrow are over. What do you say to this? Your history in the area goes way back.

The 'golden days' hark back to a time of extraction and exploitation. Golden for who? Let’s not forget the history of gold in this country. Those days were possible due to certain power structures and conditions. I have worked in Hillbrow for 18 years and remain in awe of the commitment, dedication, resilience, skill, and creativity of young people who find themselves in this difficult and culturally rich city.

French revolutionary surrealist Aimé Césaire famously asked, "Is it a small thing to create a world?" And no, it's not a small thing. Yet that’s what happens daily in Hillbrow: people create lives and a world out of nothing, out of decay and deprivation. Every day those worlds are torn down by the brutal economic and social realities of our city. Young people survive and create hope in sometimes impossible situations. They are rebuilding using improvisation, creativity, and the power of community. I would argue this is the beginning of a new path to Hillbrow’s golden era.

Can you share a story or two from your time at Hillbrow Theatre?

Aljoy Chikowo, a Zimbabwean ventriloquist, arrived in South Africa at age 15 and found his way to the Hillbrow Theatre, and was cast in a play. He was a young soccer lover with no theatre experience. He suddenly realised his capacity to move people and make them laugh. During this time at Hillbrow Theatre, he taught himself the art of ventriloquism, made himself a puppet with the help of the Boitumelo Project, and entered SA’s Got Talent, which culminated in a 'golden buzzer'. Suddenly, we had to navigate someone getting acclaim on SA’s Got Talent who wasn’t South African.

I think it's so important to keep asking that: Who belongs? How much talent and creativity do we stand to lose by closing borders? I recently encountered him, as the successful artist he is today. I said, "You look so great." His swift and succinct response was, "Yes, this is what people look like who are out of poverty." What I take away from stories like this is that, as art organisations, sometimes the most powerful role we can play is to provide space for young people to claim and reimagine. He taught himself his skills, but the Hillbrow Theatre provided a context and an environment that made that possible.

"That’s what happens daily in Hillbrow: people create lives and a world out of nothing, out of decay and deprivation."

Tell us more about the work you do at the Windybrow Arts Centre now, and what the vision for this space is.

Every afternoon the heritage home is filled with over 70 children and youth engaging in the arts programmes, and the Literacy and Homework Support Programme. Literacy is a key part of the work at the Centre – be it in developing skills, sharing our passion for reading via our Pan African Reading Rooms (which now has a dedicated librarian and is always full of young curious minds), or via the recent work our Senior Arts Group did in collaboration with Creative Writing at Wits and The Centre for the Less Good Idea, which used surrealist writing techniques to reimagine Hillbrow. It’s also about visual literary and literacy in diverse forms of performance, as well as literacy in reading the city, which allows our participants to re-see and reimagine Hillbrow. The vision is to continue to create spaces for connection, curiosity, and learning for young people to discover who they are and might become, how we interact with each other, and the world we find ourselves in.

You've said that "theatre can turn the other into us". What gives it this uniquely transformative power?

Whether it is a work of theatre, a writing workshop, reading a book, listening to music, or looking at an artwork, all have the power [to have us] see the world through each other's eyes.

The Kwasha! Theatre Company is an excellent opportunity for emerging actors – offering a year's worth of professional development and a stipend, which is rare in South Africa. What have been some of the highlights of your involvement with this project?

The two projects that remain highlights for me are the production of Frantz Fanon's The Drowning Eye, brought to Kwasha! by Tamara Guhrs and Stacy Hardy, and Skin We Are In, based on the children's book by Dr Nina Jablonski and Dr Sindiwe Magona. The Fanon play is a complex and difficult but beautiful and burning text, and I applaud the creators for their bravery in bringing this work to young performers. The joy for me was working with the actors in learning to seize the theatre’s capacity to make meaning out of words in the moment and on the floor of the rehearsal room. With Skin We Are In, I encountered the work by chance on YouTube and somehow trusted my gut instinct that it had the potential to be something special; I then engaged the authors and built an amazing creative team to realise this vision. It was arguably the first time I realised the potential power of the role of the producer.

"Sometimes, what appears to be the safest spaces are the most dangerous, and the dangerous spaces are where we can find true belonging."

What's your advice for young performing artists in South Africa today?

Be curious, learn as much as you can, develop your skills, read, collaborate, face your fears, and always do what scares you; don’t let failure trip you up – nothing is ever a failure because even things that don’t work out are a learning experience. Seize the moment, grab every opportunity, and enter every space with openness and passion.

What makes you stay in Joburg?

I was born at the Queen Victoria Hospital on Sam Hancock Street and my first home was in a flat at City Gardens in Joubert Park. I stay for the inspiring and challenging work opportunities that have been given to me in Johannesburg. I have been fortunate to have been mentored by the late Peter Ngwenya (from the Soweto Youth Drama Society), Bryan Slingers (from Volkswagen MusicActive), Sylvia Glasser, Bev Elgie, and Nhlanhla Mahlangu (from Moving into Dance). I was also inspired by the artist facilitators at the Hillbrow Theatre and the Windybrow Arts Centre. I still receive the gift of meeting incredible Johannesburg-based artists who provoke, inspire, challenge, and teach me to see the world with new perspectives.

Home is...

Where you find meaning, connection, and love.

What is a surprising thing people might learn about Joburg by having a conversation with you?

To learn Joburg is to engage multiple stories and histories – nothing is entirely what it seems. Every street corner, every building, every neighborhood, has a flip side and multiple layers of hidden histories and stories. Sometimes, what appears to be the safest spaces are the most dangerous, and the dangerous spaces are where we can find true belonging. In Johannesburg, sometimes the ugly is beautiful and the beautiful is ugly.

Your favourite Joburg suburb, and why do you choose it?

I am still inspired by Hillbrow. My childhood dream was to return to Hillbrow one day and find a flat in the sky.

What three things should a visitor not leave Joburg without seeing or experiencing?

Constitution Hill, the Apartheid Museum, and the Windybrow Arts Centre. I might get into trouble with my boss if I don't say the Market Theatre.

Your favourite Joburg author or favourite Joburg book?

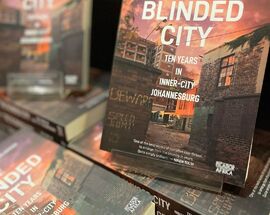

At present, The Blinded City by Matthew Wilhelm-Solomon and Tanya Zack's Wake Up, This is Joburg.

One song on your Joburg soundtrack that either is about Joburg or makes you think about this city?

Panzi Emgodini from the album Sophiatown by Junction Avenue Theatre Company.

The most memorable meal you have eaten in Joburg?

Home-cooked meals remain the best, but eating a hot waffle at Milky Lane after browsing books at Exclusive Books and records at Hillbrow Record Centre in the 70s and 80s remains in the memory.

If you could buy one Joburg building, which would it be?

Johannesburg Art Gallery. I have danced in the Louvre, but I still fantasise about having a sleepover in an art gallery.

"[Joburg] has an enormous capacity to improvise."

If you were Joburg's mayor for one day (average tenure), what would you change?

If I had a magic wand, I'd want to shift the negative perceptions of the inner city of Johannesburg.

Favourite Joburg label, and why?

Yda Walt Studio (although she has moved to Fishhoek), and Dicks Sweets (I always have a stash in my drawer – the taste reminds me of when my mom took my sister and I to their store in Eloff Street).

What makes someone a Joburger?

Someone who has not left.

What do you love most about Joburg?

It has an enormous capacity to improvise. As an improviser, a clown, and an artist, it's this capacity that gives me enormous hope for the city.

What do you least like about Joburg?

The inner city is not the best place for young people.

"There is no certainty in the world and it is through play and laughter that we sometimes find meaning."

Your number one tip for a first-time visitor to Joburg?

Find people to walk the streets with.

Who is one Joburg personality you would honour with the Freedom of the City if you could, and why?

Stacy Hardy for her radical writings, teaching pedagogies, care, and love.

The perfect weekend in Joburg includes...

A walk at Johannesburg Botanical Gardens and Emmarentia Dam, a burger at Zoo Lake Bowls Club, and popping in at Windybrow to be surprised by the centre's hidden life – an improvised jazz lesson in the parking lot and children exploring a new space and finding games and invention – cooking at home, afternoon naps, and reading a good book.

Three words that describe this city.

Tortured, uncertain, vital.

Check out some of our previous #MyJoburg interviews for more insights into the city:

#MyJoburg with Greg Homann, Market Theatre Foundation's artistic director

#MyJoburg: Sthandiwe Kgoroge on acting, vintage love, and being hidden comedy gold

#MyJoburg with Elroy Fillis-Bell, CEO of Joburg Ballet

Comments