While Lech Wałęsa came to be the face of the Solidarity movement and all of Poland in the 1980s, there were many activists who it might be argued were as responsible, if not more so, for the birth of Solidarity and the ultimate defeat of Communism in Poland that the movement helped bring about.

As the Solidarity labour movement grew and became more influential, factions began to appear and disagreements about its aims and direction broke out. Many argue to this day that Wałęsa and those around him lost sight of the values upon which the movement was built and in some way betrayed many of the millions who rallied to its flag in the early days of the movement. Others argue that it was only Wałęsa, with his obstinacy and ability to unite different parts of the opposition, aided by his team of advisors, who could have succeeded in not just bringing communism to an end but also bringing about a transition that proved relatively bloodless. But that’s for others to argue elsewhere. One thing is for certain: one of the most important members of the movement at the time of the strike in 1980, was a 50-year-old crane operator, single mother and civil rights activist, whose commitment to workers’ rights and the welfare of others marks her out as a hero of the movement and a quite remarkable character.

Anna Walentynowicz was born in Rivne, in what is now western Ukraine, on August 15, 1929. To say that she had a tough life would be something of an understatement, which makes her concern for others all the more notable. The outbreak of war saw her lose her family; her parents were killed and her brothers shipped east by the Soviet Union. She was taken in by neighbours and moved to near Warsaw. At the end of the war she began work on a farm near Gdańsk and later in a bakery and then margarine factory. In 1950 she began work in the Gdańsk (later Lenin) Shipyards as a welder where she quickly advanced to forewoman and was recognised by the authorities as a ‘Stakhanovite’ (a hero of socialist labour) for her high productivity. She was an active member of the Polish Youth Association and the Women’s League and, as if this weren’t enough, in 1952 she gave birth to a son. Unmarried, she determined to bring the child up by herself.

Walentynowicz was committed to the rights of workers from an early age and this would ultimately bring her into conflict with the very system to which she had been so committed. In 1968 she accused a supervisor of having embezzled money from a workers’ fund, but instead of punishing the supervisor the system turned on Walentynowicz and she became a marked woman. An attempt to have her fired from her job failed, in no small part to the support she received from the rest of her crew, but she was now seen as a vocal troublemaker. Walentynowicz became further disillusioned with the system following the clashes between workers and authorities in the city in 1970 which left over 40 people dead, and in 1971 formed part of a delegation which met to discuss grievances with the newly installed Polish Communist leader Edward Gierek.

But things did not improve and Walentynowicz was held by security services on a couple of occasions during the 1970s for her views. She became increasingly active, organising events to mark the anniversary of the tragedy of 1970, editing a workers’ magazine and becoming a member of the Free Trade Unions of the Coast (a forerunner of Solidarity) in 1978, all activities that would see her repeatedly held on 48-hour detentions by security forces.

It was the sacking of Walentynowicz on August 7, 1980, five months before her retirement, that sparked the unrest in the shipyard that resulted in the strike being called and the subsequent explosion of the Solidarity movement. The workers, now led by Lech Wałęsa, succeeded in having her re-instated and with pay and conditions demands and the strike was called off on August 16. But Walentynowicz (and a second woman Alina Pienkowska) urged workers not to leave the yard and instead to continue the strike to wrestle further concessions from the shipyard management.

Walentynowicz was one of the signatories for the landmark August Accords that were signed in the shipyards on August 31, 1980, which achieved among other things, the first independent trade unions in the Communist world. Walentynowicz continued to take a highly visible role in the movement but from very early on she criticised the leaders of Solidarity and in particular Wałęsa for his leadership and she was removed from the positions she held in the movement in the spring of 1981. It was rumoured that later that year security services attempted to poison her as she met workers in Radom.

This split with the leaders of Solidarity didn’t stop her from facing the same fate when Martial Law was declared in December 1981. She was interned and although released in the summer of 1982, Walentynowicz continued to be targeted by the authorities and repeatedly arrested and held over the next two years.

When the system fell in 1989, Walentynowicz remained outspoken but, unlike most of her former Solidarity colleagues, did not align herself to any of the political parties that were born over the next decade. She was a visible absentee from any Solidarity celebrations and even declined an offer of honorary citizenship of Gdansk in 2000. She did accept the Truman-Reagan Medal of Freedom on behalf of the Solidarity trade union in 2005.

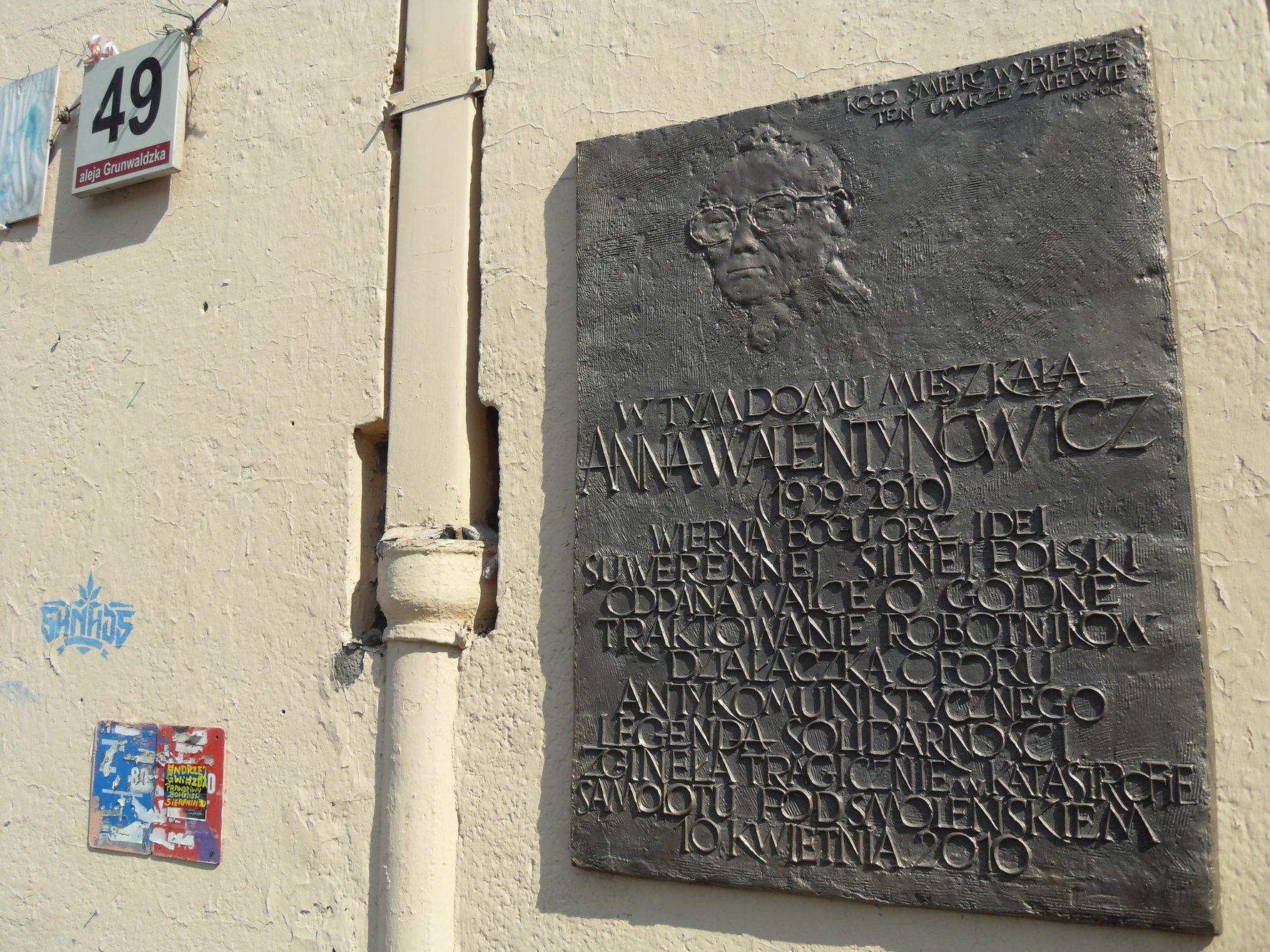

Despite the odds (as well as everything else she had overcome cancer during her thirties) she lived to the age of 85 and might still be here today had she not had the misfortune to be one of the passengers on the doomed flight to Smolensk on April 10, 2010. The plane, which was on its way to honour the dead of the Soviet murder of Polish officers at Katyn in 1940, crashed, killing all 96 people on-board, including the president Lech Kaczynski, his wife and dozens of high profile politicians and military leaders. It is still uncertain where her body is after an exhumation of her grave revealed that it was not Walentynowicz’s body that was buried there. A quite remarkable woman and for many, the unsung hero of August 1980.

Sites related to Anna Walentynowicz in Gdańsk

The Locksmith Building in Stocznia Cesarska, where Walentynowicz worked for an extensive period of time, is a key point on the area's tourist trail.The city of Gdańsk marked her memory by renaming a small piece of land close to her Wrzeszcz home as Anna Walentynowicz Square and on August 15, 2015, on the 86th anniversary of her birth, a statue was unveiled in her honour on that square.

The permanent exhibition at the European Solidarity Centre screens various oral history pieces (you actually sit in a crane-driver's cabin!) where Walentynowicz recounts her career in the Gdansk Shipyards and the events surrounding the Solidarity movement.

Comments