During the event, the Red Army made no concerted attempt to help the Poles, while promises of Allied support proved largely empty. As for the Nazi hierarchy, they reacted with blind rage to this stroke of Polish insolence, and what ensued was an epic 63-day struggle during which the Home Army faced the full wrath of Hitler. The most notorious chapter of Warsaw’s history was about to be written.

Outbreak of World War II

At 4:45am on September 1, 1939, shots were fired from German gun emplacements positioned inside the lighthouse at Danzig Neufahrwasser, located near what was then known as the Free City of Danzig (today Gdańsk). The object of the aggression was the military garrison stationed on the Polish-controlled Westerplatte Peninsula, and within minutes the German battleship Schleswig Holstein joined the bombardment, inadvertently kicking off a conflict that would last six years and cost 55 million lives.Approximately an hour after Westerplatte was fired upon, the Polish capital itself came under aerial bombardment; waves of Stuka dive bombers swooped on the capital in what can only be described as one of the world’s first-ever terror bombings – hospitals, schools, and marketplaces were all deemed legitimate targets, while columns of fleeing refugees were strafed from the air. Within a week German land forces had reached the city limits, though any thoughts of a swift lightning victory were quickly rebuffed. An opening tank assault on Ochota was fended off, with the German’s losing 80 tanks from an attacking force of 220. Spurred on by the stirring broadcasts of Warsaw Mayor Stefan Starzynski the defenders dug in for a siege, fighting street by street and inch for inch. A German demand for surrender on September 14th was rejected, and in spite of claims of triumph in the German press the city fought on, civilians and military alike joining together in a desperate attempt to ward off the invaders.

Warsaw’s fate, and indeed Poland’s, was sealed days later on the 17th of September when the Soviets invaded from the east thereby fulfilling their part in the Nazi/Soviet Molotov-Ribbentrop pact. Even so, with the odds stacked against them, the Poles continued the fight on two fronts, with segments of Chopin aired every 30 seconds by radio to let the outside world know that Warsaw was still Polish. However the human cost was starting to mount; the merciless bombardment had claimed the lives of over 50,000 Varsovians, the Royal Castle lay in ruins, and supplies of food, power and water had reached critical levels. With Allied aid not forthcoming, and a humanitarian disaster looming large, the capital finally raised the white flag on September 28th. To bring the Polish heroics into perspective, Paris, defended by the largest standing army in the world, took just nine days to fall.

Nazi Occupation

Hitler arrived in Warsaw for his one and only visit to the Polish capital on October 5th, inspecting a victory parade on Al. Ujazdowskie before scuttling off for a reception at the Belvedere Palace. If his pre-war rants hadn’t been ominous enough, the Polish public was about to learn just what a nutcase this man really was. 'The Fuhrer’s verdict on the Poles is damning,' wrote Goebbels shortly after Hitler’s stopover. 'More like animals than human beings, completely primitive, stupid and amorphous.'

Hitler carved Poland into pieces – parts were annexed into the Reich, other areas – Warsaw included – found themselves under the General Government of Hans Frank, an expert chess player and fanatical Nazi: 'If I had to put up a poster for every seven Poles I shot, the forests of Poland would not be sufficient to manufacture the paper,' he is said to have bragged. His rule was textbook despot, both brutal and bloody, and it was under his suggestion that Ludwig Fischer was appointed governor of Warsaw, a post he would hold right until 1945. Fischer was more bureaucrat than butcher, yet nonetheless it was under his authority that Warsaw became a city of blood.

The racial politics of the Reich were pursued with active intent, with whole swathes of the city set aside for Germans only. The largest Ghetto the world has ever seen was constructed to the north, and Warsaw was marginalised in importance and earmarked as a town whose true purpose would be to soak up refugees expelled from Aryan territories to the west. Chopin disappeared from his plinth, Copernicus and his statue were awarded German identity, and the Polish community alienated from their own city. Daily rations were set to 669 calories (184 for Jews), and it’s estimated that a quarter of the population was only saved from starvation by the appearance of emergency soup kitchens. But worse was to follow; from 1943 the Gestapo was granted carte blanche to shoot people on mere suspicion of wrongdoing, and street roundups and public executions became a daily occurrence. This wasn’t so much a city under occupation as a city under tyranny.

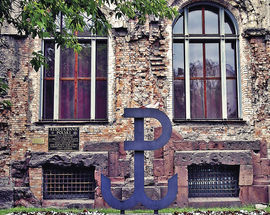

The Uprising

With such a malignant machine in force, it’s little surprise Poland gave birth to Europe’s largest resistance movement. Even still, with the war moving towards its closing stages it was far from obvious that the resistance would abandon its partisan tactics and launch a bona fide military assault on the Nazis. By July 1944 the Red Army led by Marshal Rokossovsky had reached the Wisła, and on July 22 a panicked Fischer ordered the evacuation of German civilians from Warsaw; sensitive papers were torched and destroyed, trains screeched westwards to Berlin and all the signs suggested liberation was but days away. German intelligence was aware that an uprising was possible, yet nothing seemed clear-cut. Fischer’s appeals for 100,000 Poles to present themselves to work on anti-tank defenses were ignored, as were broadcasts reminding the Poles of their heroic battle against Bolshevism in 1919-20. Tensions increased with Red Army leaflet drops urging Varsovians to arms, and were further exacerbated on July 30th with a Soviet radio announcement declaring, 'People of the capital! To arms! Strike at the Germans! May your million-strong population become a million soldiers, who will drive out the German invaders and win freedom.' Still, like boxers prowling the ring, each side appeared locked in a waiting game, so much so that German military despatches on the afternoon of August 1, 1944 concluded with, 'Warschau ist kalm.' Warsaw was anything but.

On orders from General Tadeusz ‘Bor’ Komorowski, 5pm signalled W-Hour (Wybuch standing for outbreak), the precise time when some 40,000 members of the Home Army would attack key German positions. Warsaw at the time was held by a garrison of 15,000 Germans, though any numerical supremacy the Poles could count on was offset by a chronic lack of arms and a complete dearth of heavy armor. Nonetheless, the element of surprise caught the Germans off guard, and in spite of heavy losses the Poles captured a string of strategic targets, including the old town, Prudential Tower (then the tallest building in Poland), and the post office. The first day had cost the lives of 2,000 Poles, yet for the first time since occupation, the Polish flag fluttered once more over the capital.

Yet in spite of these initial successes, their remained several concerns. Polish battle groups were spread across the city, and many had failed to link up as planned. Even more concerning, several objectives had been met with disaster – the police district around Al. Szucha remained firmly in German hands, even more importantly, so did the airport. Hitler, meanwhile, was roused out of his torpor, screaming for 'No prisoners to be taken,' and 'Every inhabitant to be shot.'

Within days German reinforcements started pouring in, and on August 5th and 6th Nazi troops rampaged through the western Wola district, massacring over 40,000 men, women and children in what would become one of the most savage episodes of the Uprising. Indeed, it was to prove a mixed first week for the Poles. In liberated areas, behind the barricades, cultural life thrived – over 130 newspapers sprang up, religious services were celebrated and a scout-run postal service introduced. Better still, the first allied airdrops hinted at the support of the west. As it turned out, this was just papering over the cracks. The Germans, under the command of the Erich von dem Bach, replied with heavy artillery, aerial attacks, armoured trains and tanks. Even worse, the practice of using Polish women as human shields was quickly introduced.

The insurgents were a mixed bag, featuring over 4,000 women in their ranks, a unit of Slovaks, scores of Jews liberated from a Warsaw concentration camp, a platoon of deaf and dumb volunteers led by an officer called Yo-Yo, and an escaped English prisoner of war called John. Fantastically ill-equipped, the one thing on their side was an almost suicidal fanaticism and belief. Casualties were almost 20 times as high as those inflicted on the Germans, yet the Poles carried on the fight with stoic self-assurance. Airdrops were vital if the uprising was to succeed, though hopes were scuppered with Stalin’s refusal to allow Allied planes landing rights in Soviet-held airports. Instead, the RAF set up a new route running from the Italian town of Brindisi to Warsaw, though casualty rates proved high with over 16% of aircraft lost, and the drops often inaccurate – one such mission concluding with 960 canisters out of a 1,000 falling into German hands. All hopes, it seemed, rested on the Russians.

After six weeks of inaction, Rokossovsky finally gave the go-ahead for a Polish force under General Berling to cross the river and relieve the insurgents. The operation was a debacle, and with heavy casualties and no headway made the assault was called off. For the Russians, this single attempt at crossing the Wisla was enough; Warsaw was on its own. Already by this time the situation in Warsaw’s Old Town, defended by 8,000 Poles, had become untenable, and a daring escape route was hatched through the sewers running under the city. The Germans were now free to focus on wiping out the remaining outposts of resistance, a task undertaken with glee and armor. Six hundred millimeter shells were landing on the centre every eight minutes, and casualties were rising to alarming rates. Surrender negotiations were initiated in early September, though it wasn’t till the end of the month – by which time all hope had been exhausted – that they took a concrete shape. Abandoned by her allies the Poles were forced to capitulate once more, some 63 days after they had taken on the Reich. 'The battle is finished,' wrote a eulogy in the final edition of the Information Bulletin. 'From the blood that has been shed, from the common toil and misery, from the pains of our bodies and souls, a new Poland will arise – free.'

Aftermath

Having deposited their weaponry at pre-designated sites, 11,668 Polish soldiers marched into German captivity, defeated but proud. The battle had cost up to 200,000 civilian lives, while military casualties between Germans and Poles would add a further 40,000 to the figure. Hitler was ecstatic; with the Uprising out of the way his plan to raze Warsaw could finally be realised. Remaining inhabitants were exiled (though around 2,000 are believed to have seen the liberation by hiding in the ruins), and the Germans set about obliterating what was left of the city. 'No stone can remain standing,' warned Himmler, and what happened next can only be described as the methodical and calculated murder of a city. Buildings were numbered according to their importance to Polish culture before being dynamited by teams of engineers, while less historic areas were simply burned to the ground. Nothing was spared the iconoclasm, not even trees. 'I have seen many towns destroyed,' exclaimed General Eisenhower after the war, 'But nowhere have I been faced with such destruction.'

Modern studies estimate the cost of damage at around 54 billion dollars. In human terms, Poland lost much more. With the Uprising died a golden generation, the very foundation a new post-war Poland could build on. Those veterans who survived were treated with suspicion and disdain by the newly installed communist government, others were persecuted for perceived western sympathies. Post-war Soviet show trials convicted 13 leaders of the Uprising for anti-Soviet actions, and thereafter the Uprising was condemned as a folly to serve the bourgeois ends of the Polish government-in-exile. Today, finally, the event that has come to define the spirit of Warsaw, has been awarded the recognition it deserves.

‘Freedom came out against slavery. The flame of the Uprising remained in people’s hearts and souls. It was passed on by the baton of the generations. The spirit proved indestructible and immortal. Soldiers of the Rising. You did not die in vain.’

-Lech Wałęsa, 1994.

Comments