As demonstrated repeatedly throughout history, Poland loves an uprising. With vast swathes of the former territories of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth under foreign occupation for parts of three consecutive centuries, and Poles steadfastly keeping the cause of independence alive throughout that entire time, it's no surprise that armed insurrections became a theme during the period of the Polish partitions. A mere thirty-two years after the failure of the November Uprising (1830-31), the cycle would repeat in what became known as the January Uprising of 1863-64. Although the January Uprising would ultimately go down as another failed attempt to overthrow Russian rule, the uprising itself was much larger in scale, and would last longer than all previous insurrections during Poland's 123 years of partition. What's more, its impact on Polish society and the Polish psyche would prove to be great, affecting events in Poland well into the 20th century.

Background & Build-up to the 'January Uprising'

Although Poles had never ceased to hope for the restoration of their fatherland, the mood across the former Polish lands began to change in 1860. Russia had recently been defeated by an allied force in the Crimean War (1853-56), which left the imperial power economically and politically weakened. This gave hope to many that in its weakened state, Poles could hope for some form of regained autonomy. There then began a series of religious and patriotic demonstrations, and resistance groups began to form, aiming to restore some form of Polish state. At this stage there was no single unifying group, but two, with opposing ideas on how this reformed state should look. The Whites, made up mostly of landowning intellectuals led by Andrzej Zamoyjski hoped to return to a pre-1830 constitutional status. The Reds, consisting of peasants and workers, followed a more democratic approach, wishing to see a state which favoured their rights.

Rising Tensions & Shots Fired

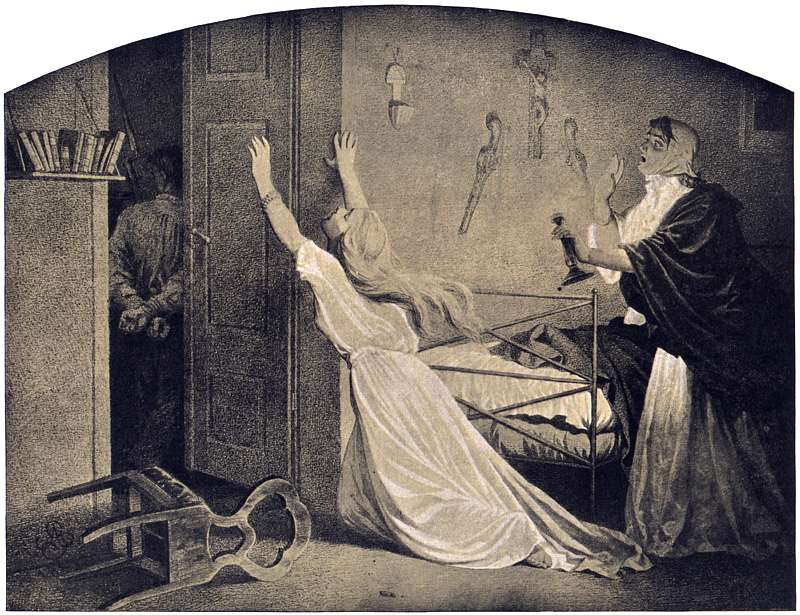

Arguably the first shots of what would be called the 'January Uprising of 1863-64' took place as early as February 1861, when Russian troops opened fire on a Polish crowd gathered on Warsaw's Castle Square to commemorate the anniversary of the 1831 Battle of Olszynka Grochowska (the largest battle of the November Uprising, and a military victory for Poland). Essentially a pro-independence/anti-Russian demonstration, five Poles were killed in the skirmish. Perhaps a little spooked and wishing to quell any further unrest, Russian Tsar Alexander II reluctantly conceded to reforms, including self-governance for small towns and counties, and the creation of a new commission for Religious Observance & Public Education, headed by Aleksander Wielopolski (a renowned Russian sympathiser). Despite this, tensions only rose and the February anniversary proved to be only a portend of things to come. Over the course of 1861, more demonstrations lead to outbreaks of violence, many resulting in deaths, followed by more repressive measures being imposed on the populace, and deportations to Siberia of anyone deemed an 'enemy of Russia.' After a demonstration on April 8, 1831 led to Russian troops killing 200 Poles and wounding 500 more, Martial law was declared in Warsaw.

By 1863, the tension was thick in the air, and plans were set in motion to begin an armed uprising in spring of the same year. Aleksander Wielopolski, fully aware of insurrectionist plans, now acted to quell the rebellion before it could begin. Using his position within the government, Wielopolski imposed forced conscription into the Russian Army, and on the night of the 14th into the 15th of January, Russian soldiers began knocking on doors in Warsaw, taking men of military age away from their families. This action had an effect completely opposite to what Wielopolski intended, with insurgents feeling they now had no option but to launch their insurrection early. And so it transpired that the call to arms went out and another uprising against imperial Russian rule was launched in the heart of winter on January 22, 1863.

Outcome & Influence of the January Uprising

Despite the odds being stacked against the insurgents from the beginning, it's the very nature of the January Uprising and its outcomes which have been remembered. From the outset, the uprising was not simply a Polish endeavour, but a multi-ethnic, multi-national campaign, riding on the back of freedom movements across Europe. Lithuanians, Belarusians, Latvians and Ukrainians all fought against the might of the Russians, joined by further volunteers from France, Hungary, Italy, and even Russia itself.

By April 1864, many of the uprising's commanders, including Traugutt, had been arrested and imprisoned in Warsaw's Citadel, where they were later executed. Severe reprisals by the Russians are what ultimately led to the Uprising's end. During and after the campaign, roughly 80,000 Poles were deported to far flung regions of Russia, which instilled fear in the general populace. Others fled to become the new wave of Polish emigres, many settling in Paris. 396 people were executed for their part in the January Uprising, many at the Warsaw Citadel. The Uprising was well and truly over, and the consequences were dire. Polish institutions were abolished, the Polish language was no longer to be taught in schools, and all Poles in senior administrative roles were replaced by Russians. Serfdom was abolished and many Polish szlachta (gentry) had their lands confiscated, which had a major impact on the already struggling peasantry. Poland was to be no more.

At least that was the intention. The effectiveness of the secret Polish state had created a template for organising cohesive covert resistance, which would prove useful again in later struggles. The result of Russian reprisals led to the growth of the "organic work" movement, aiming to nourish the notion of a Polish State through cultural and economic means. All this of course would help the Polish cause in the future, but then a set of global geopolitical events in the early 20th century led to World War I, whose aftermath resulted in the re-emergence of an independent Poland after 123 years of being absent from the maps of the world. The hopes of the January Uprising, and those rebellions which came before it, were finally realised.

Comments