Historically, Katowice, and Silesia as a whole, has passed from empire to empire over the centuries since it was first settled. Quartered at the crossroads of Europe with a diverse cultural make-up, perhaps this political tug of war (even resulting in armed conflict at times in the form of 3 uprisings) is hardly surprising, but there's one distinct factor which has always made Silesia a highly coveted territory: the region is rich in coal, known locally as 'black gold.' As a result, the area quickly developed into Central Europe's industrial heartland, with the coal and steel industries flourishing from the start.

Heavy industry across Silesia, and of course the world, has traditionally been seen as the domain of men, with husbands heading off to smelting factories or going down pits to do a dirty and exhaustive day's work, while old societal norms held that their wives stayed at home to tend the children and run the household. The fact is, however, that despite these social conventions, and even European laws explicitly preventing women from working in heavy industry, throughout Upper Silesia’s history disproportionately high numbers of women have worked in its coal and zinc industries. Let’s take a look at the role of women in Silesian industry - both those whose daily labour was down in the hole, and those whose daily work was done in the home and community.

The Role of Women in Silesian Industry

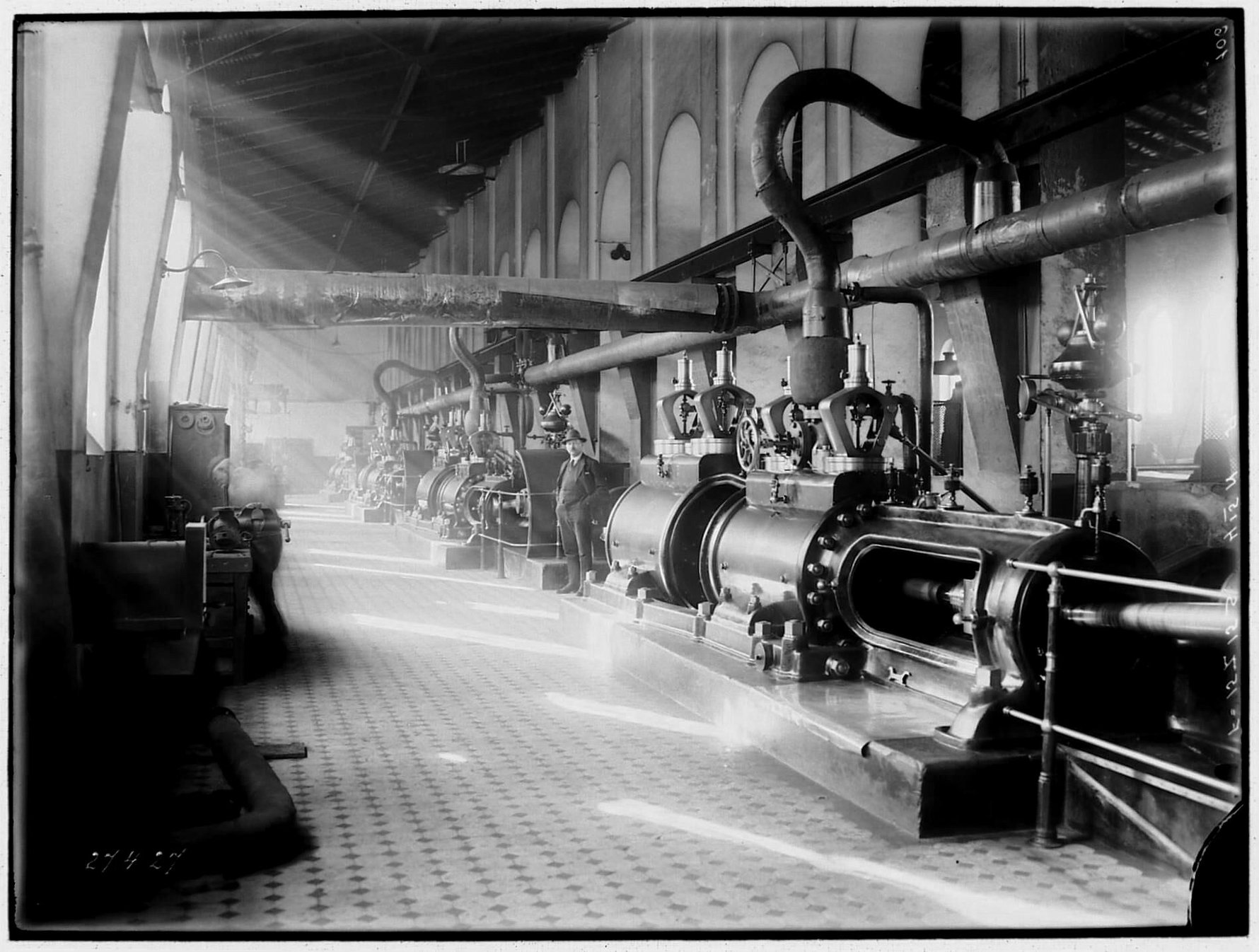

Across Europe in the late 19th-century, legislation reflected the societal and moral belief that children and women should be protected from performing labour over extended periods of time. In Imperial Germany specifically (to which Upper Silesia belonged in the 19th century), women and young girls were forbidden to work underground after 1868, the minimum age for children working in mines was raised to fourteen in 1878, and night work was outlawed for women and minors, with maximum working hours set for both. Despite this, however, the Bundesrat (German Empire 'Union Council') issued a series of edicts exempting Upper Silesian mines and smelters from certain labour restrictions until 1892, and later repeatedly extended the exemptions to 1907, 1912 and then 1922. For this reason, despite the number of women and minors employed in mining and smelting decreasing across Europe, their numbers in Upper Silesia actually increased steadily in the latter part of the 19th century. Thanks to official statistics, we know that Upper Silesian mining and smelting employed 6,800 women in 1875, 8,400 women in 1880, and 12,000 women in 1889.

In 1912, just before the outbreak of World War I, of 117,585 people employed in coal mining in Upper Silesia, 5,835 were under 16 and 5,711 were women (almost all over 16). There were an additional 2,800 females working in ore mining. For comparison, in the same year the Dortmund mining area in western Germany reported a total of 363,879 workers in coal mines, of which only 1,501 were minors and none were women. As often happens in times of war, manpower shortfalls are made up using any means possible, and in the case of both World Wars the shortfall created by men enlisting in the German military was made up by women and minors (then later propped up by slave labour). After Silesia became part of Poland following World War II, it was still not uncommon to see women - many of them recently widowed with families to provide for - doing the same hard physical labour as men.

Despite the unprecedented numbers of Silesian women employed in the industrial sector in the 19th and early 20th centuries, they were still vastly outnumbered by men at every position, of course. During Prussian rule Die Drei K (the 3 Ks) - Kinder, Küche und Kirche (Children, Kitchen and Church) - were the accepted ethos for Silesian women, with strong Catholic sensibilities the bedrock of Silesian society even today. During the communist era, Silesian miners were paid well above the average Polish salary (and still are today), allowing women whose husbands worked in the industrial sector the luxury of not working at all, with many adhering to a more traditional domestic role of raising children. Those that did pursue careers generally did so in sectors traditionally associated with women, like nursing and teaching. With most of the men in the mines and generally removed from cultural and social life, Silesian women rose to prominence and power both at home and within their communities. Although across Europe industrialisation was seen as an almost Dickensian dystopia responsible for destroying families, in Silesia it led to the emancipation of women, who were more educated and sophisticated than their male counterparts. Women organised social club and associations, including the patriotic 'Związek Towarzystw Polek' (Association of Polish Women) that even took part in the Silesian Uprisings, often in the role of nurses.

The statistics for life expectancy in Silesia at the height of industrialisation are shocking and worth noting in the larger context. The average life expectancy of men was 40, whereas women could expect to live to about 70. The reasons were simple – men would forego education to work in mines and provide for their families; many would die in mining accidents, many were sent off to fight in wars, and others would die young due to health complications connected to their vocation, not to mention alcoholism. Most women, on the other hand, did not face the dangers of the mine, their lives instead revolving around education, family and cultural life. Far more women received higher education in Silesia than men, leading to emancipation through education.

Joanna von Schaffgotsch: Industrious Silesian Lady

Going back to the early days of industrialisation in Silesia, one of the more famous names to repeatedly pop up is that of Karl Godulla (1781-1848), a Silesian self-made industrialist who came from modest beginnings. By the time of his death, he owned 80 zinc mines, 4 zinc smelters, 48 coal mines and a whole lot of land. Unmarried and childless, he had adopted a young girl, Joanna Gryzik (1842-1910), from one of his workers, who upon his passing inherited his vast estate at the tender age of six years old. By the age of 16, Friedrich Wilhelm IV of Prussia bestowed upon young Joanna a noble title, making her Gryzik von Schomberg-Godulla. Just one month later she married count Hans Ulrich von Schaffgotsch, taking the name by which we know her today: Joanna von Schaffgotsch. Also known as the ‘Silesian Cinderella,’ she was a female titan of industry who ran her business successfully right up until she split her estate between her children and grandchildren in 1906, just four years before her death.

And what of the industrious Silesian women of today? About 10% of women in Silesia are still employed in the mining industry, however 50% of those work in higher administrative positions, while the other 50% work above ground operating coal refining machinery.

There is a lot to take in with this fascinating subject and we have just scratched the surface here, but if you wish to learn more, we highly recommend visiting the Silesian Museum, and others venues listed below.

Comments