LUBLIN - AN EASTERN FRONTIER SETTLEMENT IN POLAND

Like with many other booming centres in Europe, Lublin is situated on a major historic trade route that connected the West with countries in the North and South-East of the continent. Archaeologists have identified Arabian coins from the 9th century that were found in nearby Czechów, and the oldest settlement in the area is believed to have been located on Czwartek Hill, just north of the old centre, from around the same period or earlier. However, the first notable semblance of anything that we can relate to in today's Lublin began with the fortifications on Castle Hill, which went up in the 12th century. The Donżon tower was constructed in the mid 13th century and is the oldest stone structure remaining in the city!

While Arabian-dominated trade flowed into Lublin from the east, influences from the west were making their presence known elsewhere in the young Polish state. Social elites, predominantly from the Germanic regions, clashed with Polish ruler Władysław I Łokietek (AKA Ladislaus the Elbow-High) over issues of sovereignty and trade rights. For this reason, Łokietek patronised Lublin, a promising little town in Polish territory, as a loyal subject under his rule. Lublin was also on the very eastern edge of Polish territory and frequent raids by Tatars and pagan Lithuanian tribes probably gave locals an added incentive to embrace the higher influence!

Lublin was granted town rights in 1317, exempt from Poland's tax laws and with its own self-autonomy. This is known as Magdeburg Law, a German economic ruling that had been adopted in Poland and elsewhere in the region, and, as a result, Lublin began to prosper like never before! There was also a welcomed upgrade to its defensive infrastructure, with the iconic Krakowska Gate built in 1341 along with the defensive walls once surrounded Lublin Old Town.

Lublin Old Town's perimeter follows the shape of these fortifications.

By the mid-14th century, Lublin had become a hub of thriving international trade and something of an 'ideological' capital of the Polish Kingdom, characterised by the diversity of its local inhabitants. The Dominican Order had already been in the area since the 1230s and had built a Basillica and Monastery in the centre and later the Eastern Orthodox church, Order of Jesuits and a prominent Jewish community would all call Lublin home by the 16th century. One of the most moving examples of this cross-cultural advent is the Chapel of the Holy Trinity in the castle complex. Lithuanian-born Polish King, Władysław II Jagiełło made a unique decision to commission painters from Ruthenia (now modern-day Ukraine) to create the amazing fresco works in the 1410s. The result is a stunning interior Rutheno-Byzantine artistic style, typical of an Eastern Orthodox church... and yet, most remarkably, this is a Roman Catholic chapel place of worship!

THE UNION OF LUBLIN

Władysław II Jagiełło's decision to adorn this chapel in Lublin was prophetic of the future multicultural political union that his descendants would bring into existence. The Lithuanian King's marriage to the Polish Queen Jadwiga in 1386 was a necessary alliance to save both powers from the impending threat of either one's neighbours. This began a centuries-long love affair that would culminate in the formation of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in 1569, one of the largest powers that ever existed in Europe. As for Lublin, this thriving centre conveniently lay halfway between the old Polish capital of Kraków and the Lithuanian capital of Vilnius, and somehow tied both ends of central Europe together! It's no surprise that the historic convening and treaty, known as the Union of Lublin, was signed here as well. The convergence of bigwigs from both ends of the agreement is believed to have taken place on today's Plac Litweski (Lithuanian Square) before the necessary signatures were laid down in the castle complex, followed by a service in the chapel.

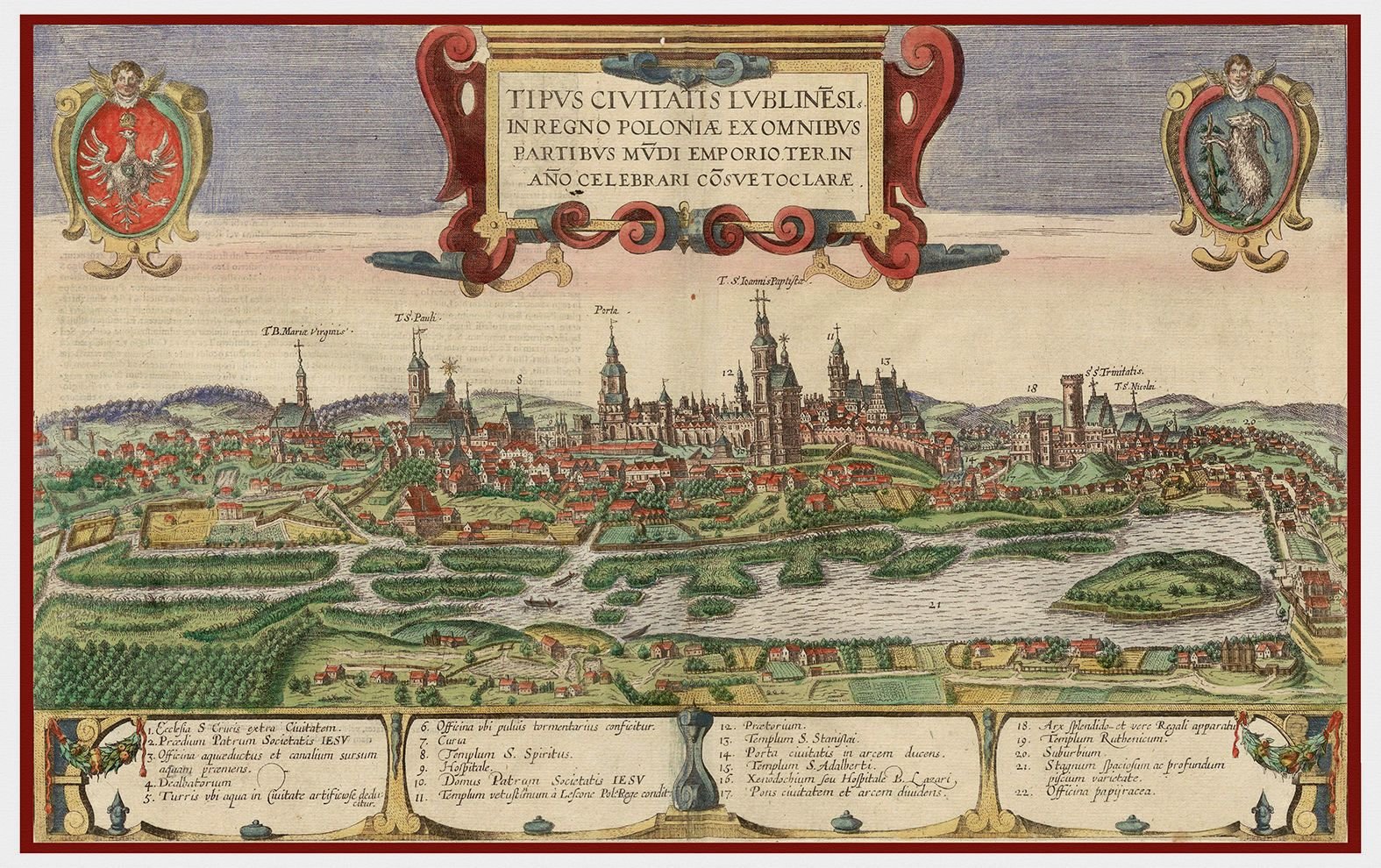

Once a frontier town on the eastern Polish border constantly having to repel attacks from its future in-laws, Lublin had finally become a city in the heart of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Former enemies now came as traders, benefiting from an exchange of commodities rather than blows. Things had been on the up and up even before the historic union, with King Kazimierz Jagiełło decreeing that a total of 4 seasonal fairs were to be held here in the calendar year. Since Lublin had become a capital of its own voivodeship in 1474, "the town of the great assembly” as it was known, drew merchants from all corners of the known world as an essential stop on the international trade route.

THE GOLDEN AGE OF LUBLIN

Now a regional capital as well an 'idealogical centre' in the newly formed Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, Lublin had now well-and-truly entered its golden age! In 1578, Lublin established its Crown Tribunal in the middle of the Old Town Rynek. This was just the first of numerous constructions that helped to boost the city’s prestige, and affluent nobility and other wealthy merchants contributed to the historic centre's now-iconic architecture. Notable constructions include the blue and white-ornamented Konopnica Family Tenement House at Rynek 22 and the yellow burgher house at Rynek 20. Nearby, the red tenement House at Rynek 8 was built by the very-prominent Lubomelski family, who were also responsible for the beautifully frescoed Fortuna Cellar and their own palace on Plac Litewski 3. The tenement house where Dom Rzemiosła can be found at Rynek 2 was the home of Lublin's very own jack-of-all-trades: Sebastian Fabian Klonowic (1545 - 1602) was the city's poet and composer, in addition to being the mayor of Lublin at one stage and a close friend of the Polish great Jan Kochanowski!

Klonowic wasn't the only bright star to emerge from the city of culture. A generation before him had produced Biernat of Lublin, a poet-physician would go on to publish the first book written in the Polish language - Raj duszny (ENG: Eden of the Soul). The sons of King Kazimierz Jagiełło, who resided at the castle in Lublin for a number of years in their youth, were tutored by Jan Długosz, the chronicler priest who is often considered to Polish historian. It is believed that Długosz made huge progress on a number of his works here and did extensive research in the archdeaconry of Lublin whilst biographing key members of the church.

This particular building is also the home of the Słodka Jewish restaurant on the ground level

This time of prosperity and openness also coincided with the emergence of Lublin's Jewish community, who were first mentioned in the second half of the 15th century. Poland's unique position on the European Jewish population is often attributed to the actions of King Kazimierz III Wielki, who enacted many protections for the community in 1334. This offered them asylum at a time when pogroms and other anti-semitic policies were commonplace elsewhere on the continent, and it continued well into the emergence of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. In Lublin, the community formed around the base of the castle, into what is now Plac Zamkowy and the nearby parklands. In 1578, Lublin's famous printing house was established by Kalonymos, the son of prominent Rabbi Mordechaj Jaffe, and published Hebrew literature and prayer books. In the 16th-17th century, the Council of Four Lands (Waad Arba Aracot) operated in Lublin, acting as a local authority for all Jews in Poland. At the turn of the 17th century, there were an 2,000 Jews living here, out of a total city population of 8,000. Later, in the 18th century, Jacob Isaac Horowitz, the father of Polish Hasidism, known as the ‘Seer of Lublin’, was born in Lublin, where he also taught and spent the end of his life. Such credentials and a general flourishing of the Hebrew sciences gave the city its nickname of the Jerusalem of the Polish Kingdom, as well as the Jewish Oxford.

The Order of Jesuits arrived in Lublin in the late 16th century, whose legacy can be seen in the street name ul. Jezuicka (ENG: Jesuit Street). Their bigger contribution, however, was the construction of Lublin Archcathedral between 1592 and 1617, which is also one of the first Baroque churches in Poland. It would later change hands to the Trinitarian Fathers in 1773, the order of which constructed the Trinitarian Tower, now offering stunning views of Lublin Old Town! It should be noted that Lublin Calvinists and Polish Brethren were first of all the most powerful citizens in the country, and both sides played a prominent role in the history of the Reformation in Poland. In the early 17th century, Lublin was an attractive town that tempted entrepreneurial and talented people, offering them opportunities for newfound wealth. As many as 12,000 were accounted for - Poles, Ruthenians, Jews, Germans, Scots, Italians, Hungarians and Armenians all continued to arrive.

DECLINE OF LUBLIN

Lublin's period of unprecedented economic growth would come to an end in the mid-17th century, as the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth descended into war with numerous surrounding powers. In 1655, the town was seized by Muscovite and Cossack armies, and later by Sweden during the Deluge (1655–1660) and Transylvanians. Conflicts with Moscow (until 1699) and Turkey (until 1699) hampered normal trade with eastern countries. Even after numerous conflicts had ended, regaining its economic strength seemed almost impossible. Although there was a brief period of recovery in the 1780s and a hopeful period for country reforms in 1791, foreign powers would descend upon the weakened Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and continue partitioning their territories.

The burnt-down Carmelite Church was converted into the New Classicist Town Hall, built in 1827. A year earlier, an enormous Neo-Gothic prison building was erected on the ruins of the Castle. In 1837, the wonderfully serene Saxon Park was arranged near the tollgate on the road to Warsaw. The Austrians had tickled the fancy of Poland's love of beer, with breweries popping up in Kraków, Tarnów and elsewhere. In 1844, Lublin's Browary Lubelskie was founded in the abandoned ruins of a monastery, which can still be visited today. Now one of Poland's most popular beers, the Perła brew would become the company's namesake in 2014, and their ground level operation is equally as popular with locals as it is with tourists! With the abolition of serfdom in the Russian empire, new opportunities to kick start industry in the region were taken advantage of, and a new upturn in growth saw the completion of the Vistula railway line from Warsaw to Kovel (now in north-western Ukraine) in 1877. In 1897, the city's population had exceeded just over 50,000, of which 24,000 were Jewish.

WWII AND THE HOLOCAUST IN LUBLIN

Lublin began World War One on the Russian side of the eastern front, however, by 1915, the city was occupied by German and Austro-Hungarian armies. Their defeat in 1918 finally saw the city back in Polish hands, and the Provisional People's Government of the Republic of Poland - the first government of newly independent Poland - operated in Lublin for a short time, before the Second Polish Republic made Warsaw its capital in 1920. In the interwar years, the city continued to modernise and its population grew; important industrial enterprises were established, including the first aviation factory in Poland, the Plage i Laśkiewicz works, later nationalised as the LWS factory. The Catholic University of Lublin, founded in 1918 and now the third oldest in the 'modern era' of Poland, aimed to create 'a harmony between science and faith'. The School of Lublin’s Wise Men (Yeshiva), founded in 1930, was soon in turned a Jewish religious college. It occupied a big edifice on ul. Lubartowska (now Collegim Maius of the Lublin School of Medicine).

The Nazi invasion of Poland took place on 1st September 1939, starting World War Two and Lublin's darkest historic period. German forces had occupied the city by September 18, 1939, with thousands of Jews from elsewhere in Poland having already sought refuge there. Lublin in the newly formed General Government territory, one of three occupation zones, and the Intelligenzaktion operation saw the Polish population became a target of severe Nazi persecutions. This focused on both Polish intelligentsia, of which thousands of teachers, judges, lawyers, engineers, lecturers, priests and students were murdered. The Gestapo used the donżon tower as a venue for interrogation and torture. As the focus turned to the local Jewish population, things were much colder and more calculated. Aside from physical attacks, many local Jews were sent to forced labour, and their property was confiscated. From November 1939, Jews were forced to wear the Jewish badge and their movements were restricted. At one stage, the Lublin district was considered as the final destination of Jewish deportation from all points of the Reich. In the spring of 1941, the Nazis ordered the establishment of a ghetto in Lublin, housing over 34,000 Jews.

Read our article on the State Museum at Majdanek.

POST-WAR LUBLIN

Lublin had faced the worst of its history and post-war Poland still hadn't achieved full independence. Falling under the veil of the Soviet Union at the end of World War II, Poland became communist under the title of the Polska Rzeczpospolita Ludowa - PRL (ENG: Polish People's Republic) and the borders shifted significantly westward. Nevertheless, Lublin remained in Polish territory, resting 100km from the Ukrainian border. Lublin growth restarted, tripling its population and greatly expanding its area. A considerable scientific and research base was established around the newly founded Maria Curie-Sklodowska University in 1945, which saw the development of the city's Botanical Gardens and nearby Open-Air Museum. A large automotive factory, Fabryka Samochodów Ciężarowych, was built in the city. Poland's unique situation as a devoutly catholic nation with a tentatively 'atheist' system of communism gave Lublin Catholic University a unique role in resisting marxist dogma that was forced upon other educational institutions at the time. 'Radical' students who had been expelled from other universities would be readily accepted here, creating a haven for communist resistance in the 50s and 60s. Earlier, the future Pope John Paul II (then Karol Wojtyła) earned a licentiate in theology there in July 1947, and would teach philosophy part-time between 1954 an 1963. Because of this association, it was later renamed to John Paul II Catholic University of Lublin.

Democratic change was on the horizon and the formation of the Solidarity trade union on the Baltic coast garnered support from all across the country, including Lublin. A wave of strikes and labour protests in 150 workplaces across the region (91 were based in Lublin) that took place from 8-24 July 1980 are now known in Polish as Lubelski Lipiec (ENG: Lublin July). Most notably, the strike committee signed an agreement with the government to increase wages, more than a month before Lech Wałęsa signed the better-known August Accords in Gdańsk! By the time free elections had been held in 1989, Lublin's population had reached 351,400. The area was slower to benefit from economic investments further west in Poland, however, since Poland's inclusion into the EU in 2004, this has begun to change.

The city is now viewed as an attractive location for living and studying, being one of the most 'cost-effective' cities in Poland. It's no surprise that the city has been selected as the 2023 European Youth Capital, challenging the culturally conservative stereotype that many apply to eastern Poland! After decades of a ruminating idea to celebrate Lublin's unique heritage, the Centre for the Meeting of Cultures was completed in 2015, with a stunning lighting facade and numerous facilities to service the creative and socially-conscious community of the city. The historic Old Town has been listed one of Poland's national monuments tracked by the National Heritage Board of Poland.

Photo by J. Scherer / Photo by the Presidential office - Marketing of the city of Lublin.

Are you planning on visiting Lublin? If so, we strongly recommend visiting by the Tourist Inspiration Centre in Lublin Old Town and getting some advice from some fun and friendly locals. If you need food (for thought), check out our Restaurants & Cafes section for our recommendations of places to eat in Lublin. As day turns to dusk and the mood takes you, it'll be time to seek out the Pubs, Clubs and Bars section. At some stage, you might need to pick up a souvenir or have the urge to check out some local art showrooms. In that case, you should cruise over to our Shopping section!

Comments