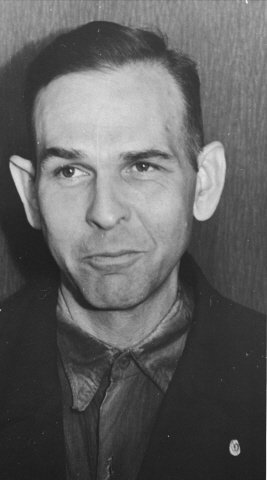

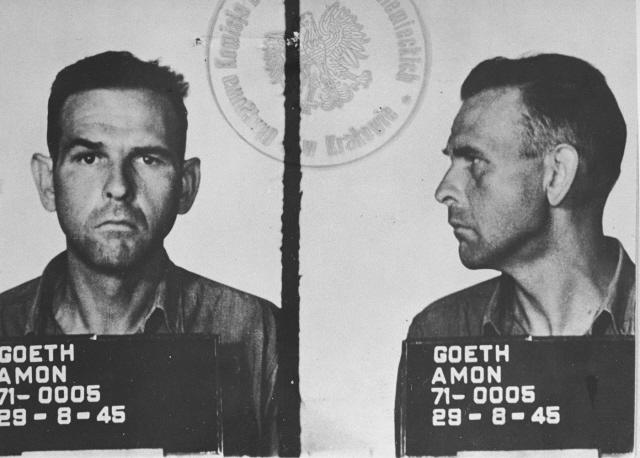

Perhaps the most internationally known icon of Nazi evil after Hitler himself, Amon Leopold Goeth (1908 – 1946) was made famous after Ralph Fiennes’ critically-acclaimed portrayal of the Kraków-Płaszów Nazi concentration camp commandant in Steven Spielberg’s highly successful film Schindler’s List. Born in Vienna, Goeth joined the Nazi party in 1932, before progressing to the ranks of the Gestapo in 1940. Originally sent to German-occupied Lublin, Goeth displayed a talent for mass slaughter during the liquidation of the Lublin Ghetto, and so impressed his superiors that he was promoted to camp commandant of Płaszów in 1943. In the same year he supervised the brutal clearing of the Kraków Ghetto in the Podgórze district, as well as the Tarnów Ghetto.

Fond of accepting bribes, Goeth used his position to steal property and valuables confiscated from Jews. Notorious for his corrupt nature, heavy drinking and bouts of extreme violence, he soon developed a reputation, even amongst his Nazi peers, as one of the most sadistic and feared men in the SS. In the words of survivor Poldek Pfefferberg, “When you saw Goeth, you saw death.” Though his characterisation in Spielberg’s film is regarded as accurate, some scenes from the film never actually occurred in real life. Goeth never murdered his stable boy (who survived the war), nor was he able to take pot shots at prisoners from his balcony, seeing that his house (which still stands today at ul. Heltmana 22) backed directly onto a hill; he did, however, exercise this apparent pleasure from a ridge overlooking the camp.

In 1944 Goeth was relieved of his position and charged with theft of Reich property, though Germany’s looming military collapse meant he was never brought to tribunal. Diagnosed with diabetes and mental illness by SS doctors he spent the remainder of the war in a sanatorium, where he was arrested by American troops in 1945. Charged with the murder of 2,000 Jews during the evacuation of the Podgórze ghetto, and 8,000 deaths during his time in Plaszów he was sentenced to death and hanged in Kraków's Montelupich prison in 1946. [Legendary footage of the execution, which depicts two failed attempts before successfully carrying out the sentence on a third try, was recently determined to not actually be of Goeth's execution, but that of Ludwig Fischer - the former Nazi Governor or Warsaw; no known footage of Goeth's execution exists.]

The legacy of the crimes committed by Goeth, who was twice married, twice divorced and the father of four children with three different women, had a significant and lasting impact not only on the lives of the families of his victims, but also his own family. Goeth’s last mistress, Ruth Irene Kalder, who had an affair with him at KL Płaszów and witnessed some of his crimes firsthand, remained loyal to him throughout her life, always keeping a portrait of Amon next to her bed and successfully applying for a name change to 'Goeth' after the war, claiming that only his death prevented their marriage. In 1983, soon after the publication of Thomas Keneally's book Schindler's Ark, Ruth Irene Goeth was interviewed by the BBC, during which she defended Amon and declared him a ‘charming man,’ even while seeing the transcript of Amon's war crimes trial for the first time. She commited suicide by overdosing on sleeping pills the following evening.

Ruth Irene had given birth to a daughter by Amon, named Monika, in November 1945; Monika never met her father but was told by her mother growing up that he was a good man and war hero. She discovered the truth as a young adult and struggled to confront it for much of her life, suffering a serious nervous breakdown after watching Spielberg's film based on Keneally's book, Schindler's List. She later participated in several book and film projects on the subject of her family history, including the 2006 film Inheritance, which documents her meeting with Płaszów survivor Helena Sternlicht, in the house where she was forced to work as Goeth's maid. In 1970, a brief relationship between Monika (today 'Monika Hertwig' after her second marriage) and a Nigerian man resulted in a daughter, Jennifer Teege. Her mother put the girl into foster care and Jennifer grew up in Germany knowing nothing of her biological family until discovering her mother's biography (Ich muss doch meinen Vater lieben, oder?/I Must Love My Father, Right?) in the Hamburg Library at age 38. Plunged into depression, she eventually processed her trauma into a memoir: My Grandfather Would Have Shot Me: A Black Woman Discovers Her Family's Nazi Past. The book was translated into several languages and the English edition became a New York Times bestseller.

Comments