Kassel History

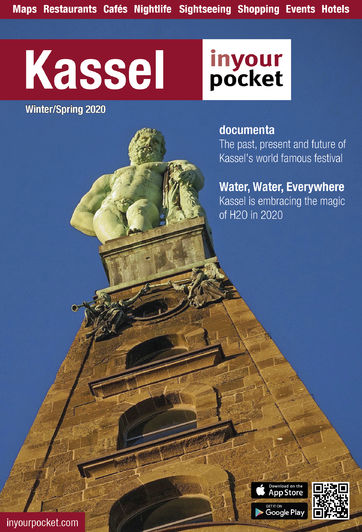

more than a year agoKassel started off in the 10th century as a fortified settlement called Chassella near the bridge across the Fulda river, documents first mention the settlement in 913. The fast-growing town was awarded city rights within the next two centuries, and surviving monuments such as the Brüderkirche, Martinskirche, Druselturm and Zwehrenturm date from this era. In 1567, with a population of around 5000, Kassel became the capital of the Hesse landgraviate. The protestant city was a refuge for fleeing French Huegenots in the 17th century, and in this period the Oberneustadt district around the Königsstrasse was built. Around 1700, under Landgrave Karl I, construction work and planting began on the Bergpark to the west of the city, with the Hercules statue erected in 1717, after a visit to a newly uncovered Hercules statue in Rome inspired the Landgrave. The grand Schloss Orangerie and the Karlsaue park by the Fulda River were built at the same time. The city's massive and modern fortifications were outdated and levelled by 1767, creating space for rapid expansion. The Landgraves built Schloss Wilhelmshöhe castle in the late 18th century, opened Germany's first theatre building and mainland Europe's first dedicated museum, and also started their valuable collections of art and scientific/technical instruments which can be admired in the city to this day. The Brothers Grimm lived in Kassel in the early 19th century and collected and wrote most of their fairy tales in the region. In 1807 Napoleon annexed Kassel, by then a city of 18,000 people, and turned it into the Kingdom of Westphalia, with present-day Germany’s very first constitution and parliament.

Industrialisation arrived in 1866, when Kassel and Hessen were part of Prussia; the famous Henschel factory east of the centre specialised in steam engines and built 12,000 of them. West of the centre, elegant residential areas were developed in this period, and Kassel soon became a city of 100,000 residents. Construction of grand state buildings took flight, and from the 1920s social housing, healthcare and sports facilities were added.

After the rise of the Nazis in the 1930s, Jews were gradually removed from public life. Kassel became a strong manufacturing and railway town, making it the base for a forced labour camps, and a prime target for Allied bombing raids. Kassel was most severely attacked on 22 October 1943, when 20 minutes of bombing completely destroyed the old city centre, killing some 10,000 people. In April 1945 Kassel was captured by the American army after heavy street battles that caused even more destruction. By the war's end in 1945, 70% of all residential buildings and 65% of industrial sites were destroyed, and only 71,000 inhabitants remained.

After the Second World War, city planners decided not to reconstruct historic old Kassel but to create a modern, accessible and car-friendly city – meaning the Altmarkt, formerly a quaint square surrounded by timber-framed houses, is now a ghastly 6-lane traffic intersection. Onthe positive side, Kassel has many well-kept and unique early 1950s buildings and projects such as the pedestrianised Treppenstrasse. Several heavily damaged but monumental buildings like the Museum Fridericianum and Orangerie were restored in the decades following the war.

Kassel was boosted further by the new university, opened in 1970, and the opening of Kassel-Wilhelmshöhe ICE station in 1991, providing fast connections to Frankfurt, Hannover and beyond.

In 1955, local painter and art teacher Arnold Bode organised the first documenta festival in order to display artworks that were considered to be ‘degenerate’ by the Nazis. Over the years, this grew to be the most important contemporary art festival in the world, and of major importance for the development of Kassel.

Comments