William Kentridge’s upcoming exhibition Studio Life Gravures opens Saturday, Nov 19 at 10:00 at the David Krut Projects Gallery. A monumental exhibition, it is the result of three years of cross-continental collaboration between William Kentridge, David Krut Workshop, Jillian Ross Print and photogravure experts Steven Dixon in Edmonton, Canada and Zahne Warren in Cape Town, South Africa.

It comes at a time when William Kentridge is the artist of the moment – having opened a show at Royal Academy of the Arts in London (until Dec 11), and about to open at The Broad in Los Angeles (Nov 12-Apr 09). A prolific artist with more than 265v solo shows under his belt, world-renowned, and highly acclaimed as a master of many mediums, William Kentridge's world is a fascinating one.

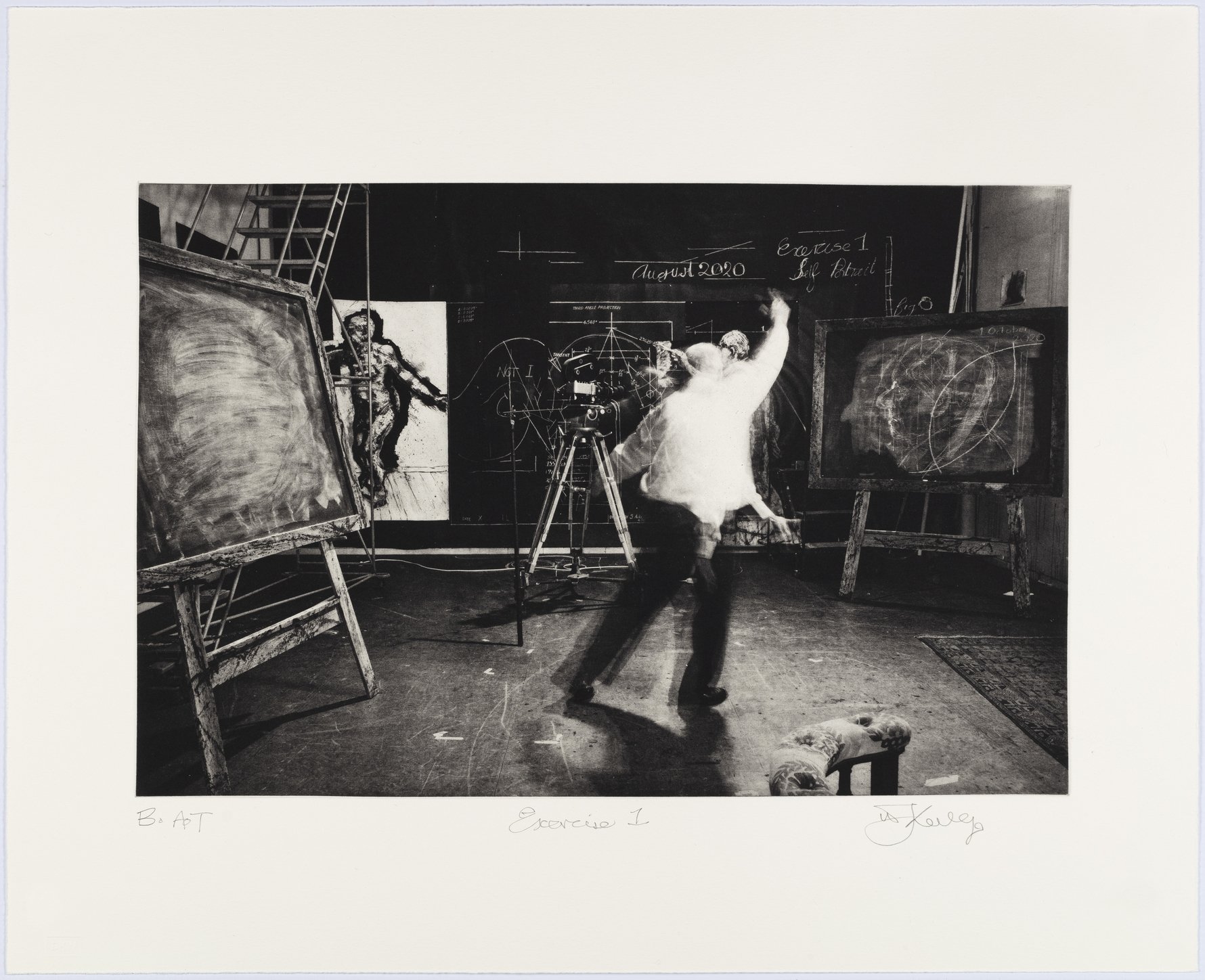

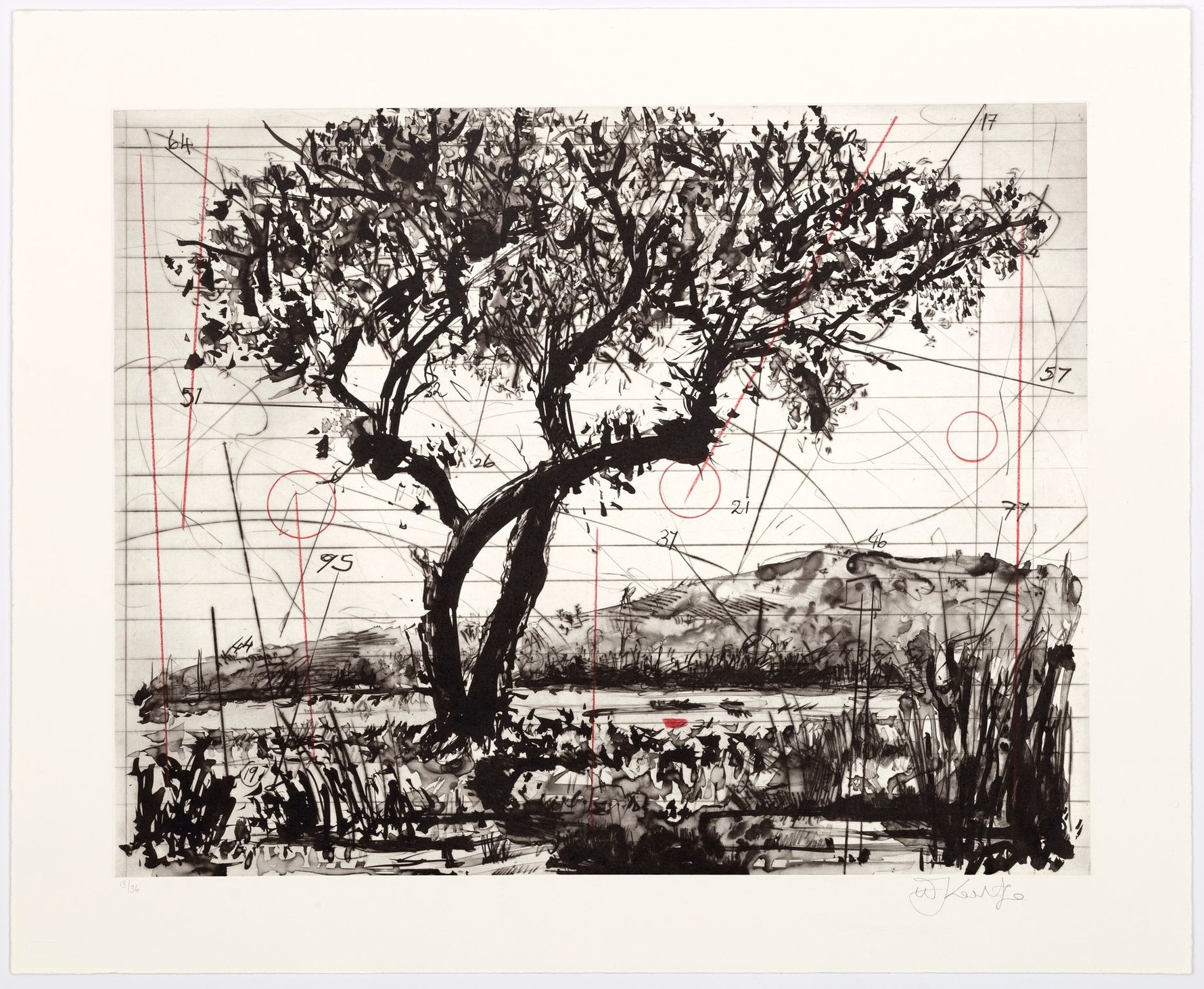

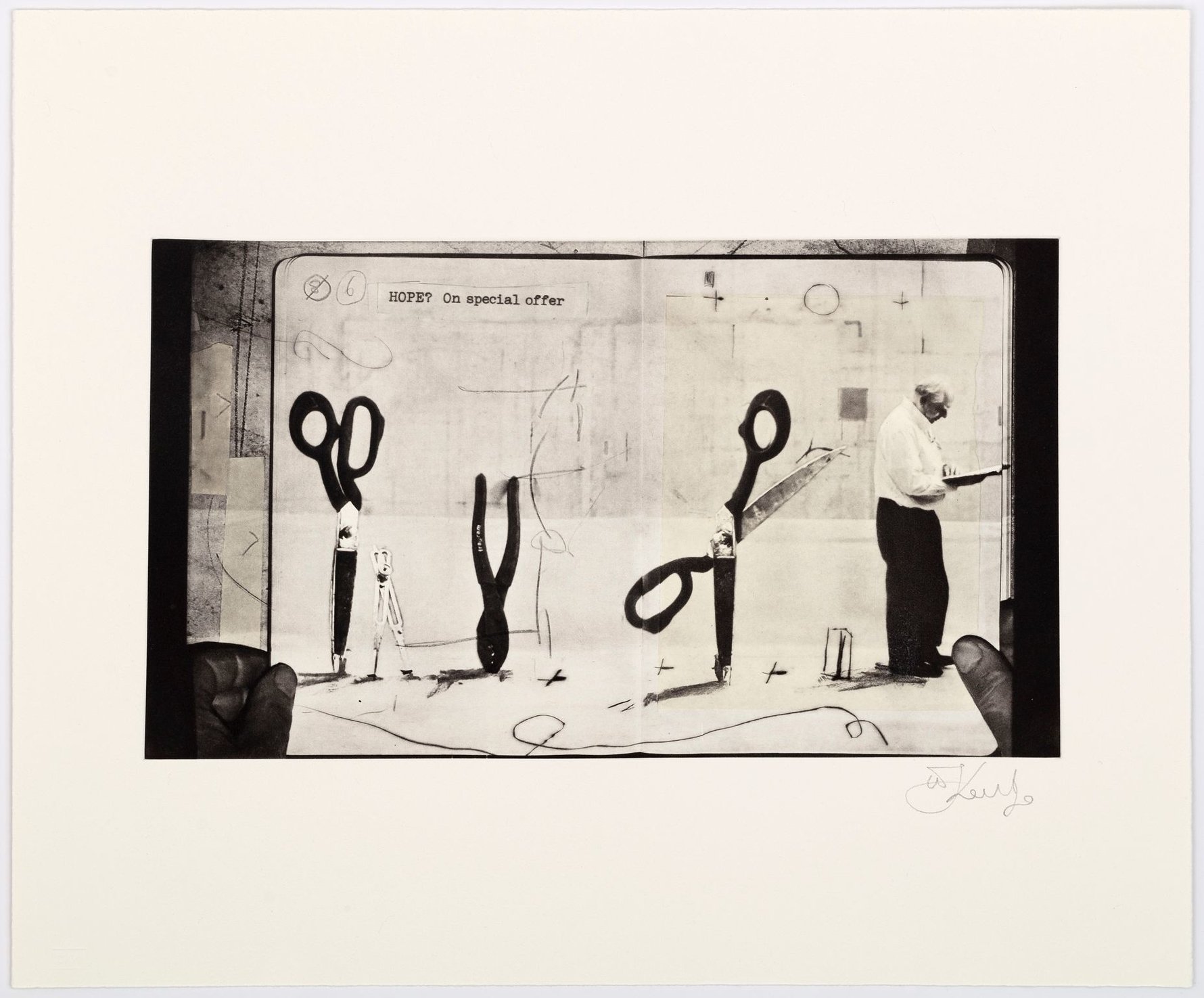

Studio Life Gravures explores the role of the studio in Kentridge’s artistic process. How does it influence meaning in his artworks? What objects are present in the studio? How is it organised? And in what ways is the studio's make-up a reflection of him and his work? It allows us to be voyeurs into this intimate and usually closed-off space. The exhibition features stills from his new nine-part film Self-Portrait as a Coffee Pot as well as cellphone and hi-res photos of his work on the Laocoön sculpture, Beckman’s Self-Portrait with Jam Jar and Scissors and The Old Gods Have Retired. The result is an operatic look at the studio and the artist where “the dance of art making becomes a riveting storyline delivered with Shakespearean precision” (David Krut Projects).

"The result is an operatic look at the studio and the artist where “the dance of art making becomes a riveting storyline delivered with Shakespearean precision”"

While the exhibition focuses on Kentridge's Houghton studio, the work has been put together globally in studios in Canada, the David Krut Workshop and Kentridge’s studio. To get a sense of the collaborative process and the roles these different spaces and people have played, we spoke with master printer and long-time Kentridge collaborator, Jillian Ross of Jillian Ross Print and the David Krut Projects team.

Jillian Ross is a leading master printer whose close collaboration with William Kentridge for over two decades has resulted in some of the world’s most astonishing artworks. Ross was based at the David Krut Workshop as the lead printer for 16 years before moving to Canada in 2020 to start her studio, Jillian Ross Print, a collaborative print studio working with Canadian and South African artists. Ross first worked with Kentridge on his project Dove in 2006. Their 16 years of working together have been incredibly productive and together they have created more than 160 prints. In 2020 at the height of the pandemic Ross and Kentridge once again found themselves working together with Kentridge’s Studio Life Gravures.

What were your thoughts the first time you found out you would be working with William Kentridge?

I was excited but very nervous. At the time I started working on his prints, I was still a novice printmaker. William was, and is, very generous with sharing his time and his knowledge, which makes him such a successful collaborator. William showed me how to work collaboratively with an artist, and how to experiment with different techniques until a print achieves an artist’s vision. Working with William in these early years was instrumental in the development of my current collaborative working practices and in building new, strong teams.

Which of the projects that you worked on with Kentridge did you enjoy the most?

I’ve always enjoyed the initial excitement of a project and the struggle to find the right way forward for each artwork. It’s rewarding to watch a project develop and then to see the final results before you. It is hard for me to choose which project I enjoyed the most. However, my interest in scale began with Kentridge’s Scribble Cat (2010). We had just opened the David Krut Workshop at Arts on Main. The new space – next door to William’s 2nd studio – allowed for easy and continuous collaboration. William had suggested making a large cat etching using six large sheets of copper; the prints would then be collaged and pinned together to make the final piece.

My logical printer’s approach was to place each overlapping sheet side-by-side in a grid format. Instead, William’s artistic approach was to choose to re-arrange and tilt each of the sheets, add red registration marks, and hand-paint each print in a slightly different way. In the end, I had to adjust the paper borders to balance the print and, as the sheets weren't straight, I had to re-make this work many times to prepare it for editioning. Figuring out the arrangement of sheets, making an instruction sheet for framing, and sharing how the prints were made with visitors in the studio started me thinking differently.

Which project has challenged you the most as a printmaker?

Many of my projects with William are works in a series. Each of his series has most often used a different printing technique and has always incorporated new team members. For each new technique, I tested and explored the mark-making possibilities and pushed boundaries. Often the challenges arrive as the series develops. For example, I found The Flood, the second print from the Triumphs and Laments Woodcuts series, very challenging. We were editioning the new, large-scale Mantegna at the same time that we were beginning The Flood. Mantegna was made from 21 sheets of overlapping paper and used four different types of woodgrains. For The Flood, we decided to add two additional timbers into the mix and carve lots of additional detail in specific areas. As I didn’t want the prints to get overly technical, it was also a challenge for the carving team of six printers. Prints need elements of spontaneity to have a soul.

The world has changed a lot since this new project was started in 2020, first with Covid and then for you with your move to Canada. Tell us about the impact on your work.

Pre-covid I was very rarely alone in the studio. Working in isolation and being physically separated from the DKW team was incredibly difficult for me. Continuously changing Covid protocols changed ways of working forever. Boundaries were pushed and pulled apart; working from different countries was difficult but possible.

Learning a new technique through trial and error while testing the process of different mark-making and technical aspects of a medium is common practice for me, but the incredible physical distance between my studio and William’s and working without the team at DKW was very hard.

Then I began to see my re-location as a sabbatical and much-needed time to find re-focus. Having time to consider printing suggestions is quite a luxury and now I had it. I would send regular videos and texts to keep communication strong. I was able to work more hands-on, albeit more slowly, but also more deliberately too. My current projects are no less complex, but I feel as if I am exploring new pathways and pushing new projects in a considered way.

What was it like working on these gravures under lockdown and having to collaborate over such large distances?

A photogravure is a very technical challenge and lockdown imposed physical restrictions. With travel being an impossibility in 2020, William suggested that I find a studio in Canada that worked in large-scale photogravures. This suggestion set in motion the last two years of my studio practice. Photogravure is a technique that can work from a distance as the artist need not be present when the plate is made. It is an art form in processing the plates and an entirely different art form in printing them. The range of ways to make and print the plates has been the most interesting exploration for me.

William has made photogravure images for over 20 years and documented aspects of his studio practice over this time. It was a natural way of working together during lockdown. While he suggested the series Studio Life be made and printed in SA, he also suggested the possibility of making these larger-scale works together from afar.

We travelled to Edmonton, Alberta, to make Eight Vessels over five days in the studio at the University of Alberta in September 2020. We created the plates with technician Steven Dixon and his team whom we had just met. Restrictions at the time were very intense, and it was quite a challenge making and printing these plates in the time allowed. For months thereafter, without my studio, I worked from a rented studio space and sent prints back and forth to William in the mail. The process was like writing letters back and forth. Brendan Copestake, my partner in Jillian Ross Print, solved all of the logistical puzzles of shipping and sourcing materials while William and I focused on the artistic nature of the collaboration. In early 2022, William and I met in London where much of the recent project – including direct gravures and The Old Gods Have Retired – was conceived. Plate-making began at the University of Alberta in June/July 2022 and the resulting 27 copper plates, weighing over 200 kg, were shipped to Johannesburg. Although work can be created from a distance, it is only by working side-by-side that the project grows, and all parties really align. It was an absolute pleasure returning to Johannesburg in August/September 2022 and working with William and DKW on concluding this series of works.

"Collaboration is really exciting. Open conversation is key: asking questions and listening to responses is important."

The large-scale Eight Vessels (2020) is made from four overlapping sheets of paper, during the height of the pandemic. The Old Gods Have Retired (2022) is made from 12 large overlapping sheets of paper and 67 collaged pages, many hand-painted. Both have been created as translations of drawings that William created in 2020. The way they have been re-created in print, with many layers of overlapping pieces, is reminiscent of T&L Woodcuts (2016 – 2020) and Scribble Cat (2010).

How does the nature of collaboration change when you are working with a new artist as opposed to when you are working with someone like William Kentridge with whom you have a long-standing working relationship?

Collaboration is really exciting. Open conversation is key: asking questions and listening to responses is important. It takes many conversations and shared experiences in the studio to get to know one another. With a new artist, I need to learn how to interpret their visual language, what options to provide them with as trial proofs, and how to share technical information, but also not too much, so they can explore it themselves.

I enjoy getting to know new artists, yet I love the ease of familiarity when working with long-time collaborators. William and I communicate easily as we work together; the flow is very natural. He responds very quickly to each new print that comes off the press, and I look forward to hearing which element to pursue once tests have begun. I am at my best when working on multiple projects simultaneously. Whilst working on one print project, it allows pause for the other project and problems find easy solutions. Some projects can easily take a year to take shape and find their place.

This new exhibition sees Kentridge exploring the significance of his studio, its place in the world and his practices within it. How is this reflected in the work?

I received a text message from William in April 2020 where he wrote he believed he’d found the foundation for his next big project – a series of films based on life in his studio. He sent a few photographs of drawings he was working on at the time and a newspaper article entitled ‘Solidarity – pandemic’s first victim’. Through images and videos shared by William over What’s App, I watched the film series develop and grow and eventually was able to watch many of the final episodes of the series.

"South Africa’s cultural sector is bubbling with energy, and there is a fantastic cross-over between the creative industries such as fashion, design, architecture, and contemporary arts."

The photogravure series we’ve created explores all the facets of making this series of films as it was being made in real-time. The photographic images of Studio Life (2020 – 2022) are an outsider’s look into the studio, what William is working on, and what he sees as he is making. It is a visual recording of many projects and drawings worked on over two years and includes Eight Vessels (2020) and The Old Gods Have Retired (2022); both are very large, complex pieces featured in the early episodes.

Can you explain the significance of your workshop to your printmaking process?

My studio experience is no longer limited to my own physical space. Collaborative printmaking allows me to work in different studios with different printmakers. Each studio and each printmaker has different skills, equipment, and technical approaches. These experiences have broadened my practice and my ability to work with other artists and teams that I wouldn’t previously have been able to work with due to geographical restraints. The pandemic that forced my move and the imposed isolation time also gave me time to reflect on my studio life. I now more easily carry “my studio” with me to each new physical space.

In South Africa, printmaking is such an exciting and established part of the art world. How does it differ from Canada?

Collaborative print studios are flourishing in South Africa. Many established artists have been working in the medium for many years and young artists are now too exploring its many techniques, and that’s wonderful. This is due to the nurturing and supportive printmaking community and the energy generated by artists working in the long-standing studios of The Artists’ Press, David Krut Workshop, and Artist Proof Studio. This energy and passion for printmaking led to the emergence of several new studios in the last 10 to 15 years. South Africa’s cultural sector is bubbling with energy, and there is a fantastic cross-over between the creative industries such as fashion, design, architecture, and contemporary arts.

Since my relocation to Saskatchewan in 2020, I have found that passion for printmaking in the larger communities of Western Canada. Of particular note are the leaders within the Fine Arts Department at the University of Edmonton in Alberta and Emily Carr University in British Columbia who are nurturing the next generation. These printmaking studio facilities are absolutely incredible and have a lot of government support and funding opportunities.

What has the experience been like starting and running your printing studio Jillian Ross Print?

In 2020, Covid regulations made work challenging, but it also provided me time to reflect and think through new ideas. In 2021, I was artist-in-residence at both Griffin Art Projects in Vancouver and the University of Alberta in Edmonton and my husband, Brendan Copestake, and I decided to open Jillian Ross Print. We have travelled a lot as our starting point to build new projects and share existing works with a new audience. It’s only in 2022 that we have a space that allows us enough room to start making prints in our own studio space. It has taken us two years to gain momentum; many projects are now underway. The last two years have taught us that there are many ways forward with new and existing collaborative partners.

Do you see the start of this studio as a natural development from being lead printer at David Krut?

I loved leading the team at David Krut Workshop. It was and is a pleasure working with DKW printers Sbongiseni Khulu, Kim-Lee Loggenberg, Sarah Hunkin, and Roxy Kaczmarek and all of the artists I had the pleasure of working with over 16 years in SA. I now love seeing them rise to new challenges and continue to make beautiful work. In my relocation to Canada, it is natural to start my studio and train new printers and nurture and enable artists to work in the art form.

What are your goals for your studio?

To grow within my community in Canada and stay connected to South Africa.

In an interview with David Krut Projects, you speak about printmaking being like assembling different pieces of the puzzle. For those unfamiliar with printmaking what are these pieces and why do you see it as a type of puzzle?

Every print made can be made in a variety of different ways. Every artist approaches making work in a different way. Working collaboratively means there is a common thread of conversation and understanding; this too is a puzzle. Each puzzle has two components to it: a technical puzzle on how to make the print and an artistic puzzle on how to make the print as to how the artist imagines it to be. Merging those two puzzles is the real challenge as it requires both the scientific brain and the artistic brain to be in sync.

Are the printers you’re working with within the new studio printers you worked with before or is it a new team? If the latter, what has it been like getting to know their different methods and ways of working when you had been with an established team at David Krut for so long?

I have been working with two new collaborators from the University of Alberta for two years now, and I have worked with many of the printers at DKW for three to eight years. I am very lucky to be able to work with all of these great and talented people. It’s hard getting to know each other at first but with the experience of each project, it is quite natural to see where each printer’s interest and skill set lie and where to place focus. We have to work together with the artist, as a team, to draw on each other’s strengths to produce the best work possible. I love seeing how the process of a project comes to life.

What do you miss about Johannesburg?

The people.

What don’t you miss?

The daily commute.

Your studio still has clear goals of wanting to work with South African artists. What potential do you see for collaboration across continents?

I have made a home in both South Africa and Canada, and I have strong links to both. Potential comes from wanting to work in both places and from creating opportunities to share and work collaboratively. Ideas grow once there is a seed planted; we have been planting seeds and hope some of those ideas take root.

How has the Studio Life series changed your ideas about collaboration?

The Studio Life series broadened my thinking and stretched my boundaries. It made me think as big as I could think. Collaboration holds strong and working with William, the Kentridge Studio, David Krut, Amé Bell, the team at DKW, Zhané Warren, Steven Dixon, and Luke Johnson is fantastic. Every collaborator is working at their strength, and what a pleasure it is working together.

To read more about this exhibition and for our interview with the David Krut Projects team click here. Exhibition opens Sat, Nov 19 at 11:00 at David Krut Projects Gallery.

Comments