"I think that the sense of things falling apart, yet holding together, that has found its way into my work mirrors the same sense of Joburg falling into disrepair, yet somehow retaining itself."

Bev Butkow is a Johannesburg-based artist whose solo exhibition, re-weaving m/other, is currently showing at Origins Centre at Wits University in Braamfontein. Alongside the exhibition is a series of Creative Gatherings taking place on Wed at 16:00 on Sep 6, 13 and 20. These are free to attend. See the programme here and reserve your seat with Tammy.Hodgskiss@wits.ac.za

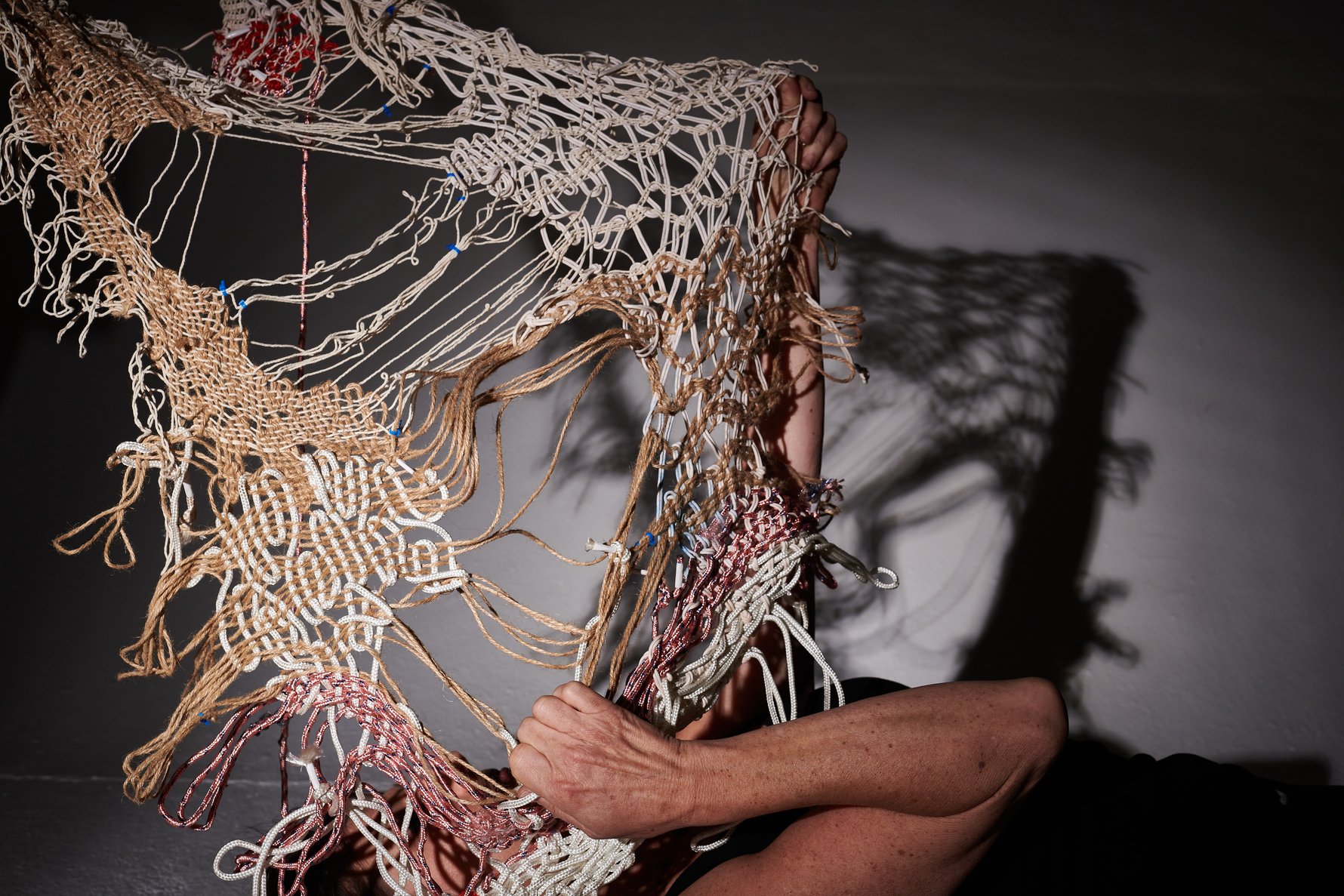

Photo: Anthea Pokroy, Guns & Rain.

In this exhibition, the artist has carefully crafted a space that reframes how we exist in the world, and why we should care about how we share it with others. In a room full of curious woven experimentation, Bev Butkow's networks of care have been painted, woven, installed and projected into physical pieces, that immerse the viewer into an entanglement of compassion.

From a creative perspective, the provocations in Butkow’s work allow for a much wider conversation, not only about our existence in relation to the world, how we live in it and the space we take up, but it also opens up a conversation about women’s work – in this case, weaving – as an artistic practice.

The entire exhibition invites the viewer into a space of collaboration and community. It’s thanks to the collaborative efforts of other creatives and speakers joining in on the artist's conversation that we can dive into important issues like the body and art, how materials ‘speak’, the value of women’s labour and the traces we leave upon the Earth – all topics that form part of the Creative Gatherings running in conjunction with the exhibition. As part of her art-making process, Butkow questions, “What ethical, moral and material responsibilities do I have to the traces that I leave? How do I walk upon this Earth?”

We were curious to find out more.

What drew you to create works that rely on a viewer’s somatic response to your tactile installation?

There is a strong parallel to my personal transition from being an accountant with a career in corporate finance to being an artist. I wanted to break the "stuckness" and control I felt in my body. To move from foregrounding my intellect as my primary mode of being in the world, towards a place of being more in touch with my body. This has been a journey of becoming more intuitive. It has meant trusting that my process is guided and that what I do is for a greater purpose. We are socialised to prioritise our minds ahead of our bodies. I want my work to challenge that. And to challenge the expectations of how we are “meant” to engage with artworks. re-weaving m/other reminds us to engage in the world through our bodies, senses and instincts, rather than through our head and intellect. The encounter with re-weaving m/other re-awakens the body, bringing subversive possibilities of experiencing the world in more embodied ways. Such a small proportion of the way humans communicate happens verbally. The vast majority of our interactions happen through our bodies, and increasing awareness of our bodies will help us interact with greater clarity and awareness.

There is a growing movement globally towards reconstituting the perceptive body as both a location of individual sensory experiences, so that we feel through our bodies more, and also to use the body as a tool for broader social, communal and political realignment.

Art-making inherently relies on material objects to convey a message. What were the challenges of creating an awareness of the responsibilities that come with making material objects?

I feel deeply that each of us has a responsibility to consider the traces we leave as we walk upon this beautiful Earth. We are responsible for our actions, the words we impart and their consequences. Everything we do has an impact around us, and its ripples are felt long after. I locate my sense of responsibility, as both a person and an artist, in an ethos of mothering, nurturing, caring. This presence of care pervades my making – care for my tactile human-made materials, for an ailing planet, for the body and for one another. It is from this perspective that I ask how I both nurture and expand the people and the things around me.

I’m very aware of the inherent contradiction in making material forms that aim to bring awareness to the excesses, the muchness, of our material lives. How complicit am I in building more excess – why are the forms I make worthy of being made and of cluttering our over-cluttered world even more?

How do I treat every human being I come in contact with? How do I make them feel? Why is my story important to tell? What impact can it have? Where am I covering up an uncomfortable truth? Where am I not being sufficiently honest and vulnerable?

"I wrestle constantly with these questions of my responsibility, avoiding shallow attempts to answer them. I rather sit with the discomfort of the questions... like a stone in my shoe that reminds me to ask the questions often."

You are a Joburg artist. What does that mean to you?

Since I started making art, I’ve had a studio around Newtown or the City Centre. Joburg is so deeply entwined in my making practice that they are inseparable. Being the only city I have ever lived in, the City Centre is closely linked to my life experiences, including those of my childhood and my family’s generational past. My grandfather sold eggs at the Fresh Produce Market in Newtown; my first job was in central Joburg, and I spent a lot of time in the City Centre.

How I understand myself and my past is entwined in Joburg, which is central to my make-up as a person. I think that one of the big opportunities for me is to use creative making to better understand myself as a South African. Learning about the city invariably means learning about myself too. This understanding brings a layered and nuanced understanding of the self. The city is my energy, my fuel and my inspiration and, sadly, more and more so recently, it is my shame.

How has the city impacted upon your work as an artist?

As I traverse the city from the leafy green suburbs to the City Centre, the sense of Joburg and what it is changes so much, becoming grittier and more varied. Each area has its own character; its own pulse. Ever since I’ve had an accessible phone, I’ve taken photos of scenes around me: water on the road that provides a reflective glimmer; a plastic packet blowing in the wind. My daily car rides into the city imprint scenes, and flashes of someone’s daily experiences into me. Images of these scenes swim around me and are imprinted within me. The sense of these multiple traces stays with me as I work in the studio.

The process of making art accesses the worldly experiences that are embodied in me. Through my creative process, a sense, feeling, trace or energy of these scenes unwittingly make their way into my work. Even though my work is more referential than representative, I think that the sense of things falling apart, yet holding together, that has found its way into my work mirrors the same sense of Joburg falling into disrepair, yet somehow retaining itself. There is a sense within my made forms that they misbehave, and break rules and expectations, in ways that feel a lot like Joburg and her residents.

Under the double-decker section of the highway, in the entrance doorway of an abandoned building is a tumble of barbed wire that seems to explode out the doorway. Bits of trash have got stuck in the wire. It was a shock to me to recognise this form in my studio, in a sculptural wire and fabric piece that seems to expand and grow in my space.

"There is a sense within my made forms that they misbehave, break rules and expectations, in ways that feel a lot like Joburg and her residents."

Were there criteria you tried to adhere to in the making of this exhibition?

I have a small piece of paper in my studio that contains these broad ‘rules’ of engagement:

– Put the works at risk

– Transgress

– Eliminate preciousness

– Let the process feed itself

– Ask the work to find its wildness through obsessiveness

– Radically transform. And then embed more layers of transformations

– Inculcate contradiction

– Listen and sense deeply

Having completed making the work for this exhibition, my task is to now look objectively to see if I lived up to these challenges.

How did you choose your material and what is the significance?

As a child, I found scraps of materials and buttons and neatly folded, but already used, gift wrapping paper while rummaging through my grandmother’s drawers. My grandmother had escaped Lithuania and thereby survived World War II. Inside her drawers were a collection of things that others would have tossed away as trash. Plastic being the useful substance that it is, covered my grandparent’s couch. I recognise my grandmother’s frugality as coming from need. But it also comes from a recognition of the value of each material object. It stands in such contrast to the culture of excess and accumulation that is so pervasive in our world today.

My grandmother’s scraps have found their way into my forms with a nostalgic sentimentality. I create something of enduring and abiding beauty out of dressmaking scraps, threads and beads. It is apparent that my works are a homage to my grandmother’s suffering and her survival. And those of my ancestors before her. I am a witness to it, and it has become part of my rhythm of making. I am drawn to the specificity of the textures, shapes, colour and feel of mundane scraps. I turn this detritus into something with preciousness and value. Materials speak to me. I honour them and let them tell my story.

Did you choose to keep certain material out of the exhibition?

I have collected heaps of cardboard boxes and wooden beams in my studio during the course of thinking about, planning and making this exhibition. My studio looks like a scrap collection centre. I had intended to use them in the show but decided against it while I was curating. This is because the exhibition space at the Origins Centre has a very strong architectural presence – it is all concrete, with interesting angles and overhanging beams. I felt it needed softening, and not more solid, rigid materials. So my studio remains a waste collection centre, full of materials waiting for their turn to shine.

"I am drawn to the specificity of the textures, shapes, colour and feel of mundane scraps... Materials speak to me. I honour them and let them tell my story."

As an artist with a keen interest in embodied materiality, how has it felt to see people walk within your space, and engage with and interact with your work?

It’s amazing. I encourage audiences to touch and engage with my work and get excited when they do. Interestingly, many adults ask permission to touch, and I can see the liberation when they realise they can. Children are less inhibited, knowing instinctively that they can touch. In designing the exhibition, I planned for the space to be a space of exploration, discovery, reflection and contemplation. As viewers walk into the exhibition space, projected animation swims around them and multiple tactile threads [are] touching their bodies. The space signals that it requires a different type of engagement. Intimate encounters with materials and forms activate the viewer’s senses beyond sight, as they listen, engage and feel. Hands and fingers touch the tactile works; audiences bend down to examine the floor; heads crane upwards and thereby, they remember their body and its spatial connection with the space.

The [audience] is invited to suspend disbelief and feel experientially and immersively through their bodies. re-weaving m/other offers a non-traditional, improvisational, transitory, intimate and vulnerable sensory experience that they must explore for themselves.

Is your aim to document the viewer’s interaction with re-weaving m/other?

It’s a great question and one I need to think about more. I haven’t specifically been documenting the viewer’s reaction to the work. But the traces of your interaction with the work remain within the work, adding another layer of energy to the networks of connection that make them up. Through the audience’s interactions with the works, richer and more resonant fields of energy or auras build around them. As a person who experienced the work, you become an integral part of it. My site-specific installation is ephemeral by nature, and when it comes down, all that will remain are the feelings in our bodies and the photos we’ve taken.

Collaboration is a big part of your art-making process. Has working with other creatives changed your message, or opened your mind to a new way of thinking?

Absolutely! Every conversation, every challenge, with another thinker and maker opens my eyes and my mind to broader perspectives, both around my practice and more generally about the world. As an example, I work with the most wonderful writer David Mann, who is a very deep thinker. Our process has been to think and write not about my work but through my work, the materials, and the messy, sticky material process of making. Our process could maybe be described as sitting patiently and slowly in messy things to see what arises.

Paradoxically, engaging over a period of time with David is teaching me to communicate more succinctly and clearly about my work, while at the same time, I’m learning to think in more complex and deeper ways about it. I have gained hugely from our ongoing conversations and writing together, and David reflects similarly that having something material to work with is deepening his engagement and writing. I love that each collaborator brings something new and generative. Each brings a new layer to my ever-deepening process.

How do you trust your hands to weave the right story?

The iterative, repetitive rhythmic, performative labour of weaving helps me reawaken my body to rediscover an innate rhythm. Weaving is a remembered action. It remembers and reclaims instinctive bodily rhythms through which I can access intuitive knowledge. For me, weaving feels like an un-learning and a re-learning of an instinctual rhythm.

Where does the process start? Do you finish where you imagined when working in a collaborative way?

My process starts on the floor, sitting amongst my materials. It starts with an exploration, experimenting, playing, forming, breaking and remaking. From there, material forms emerge. I let them grow without any expectations of what they might be... I never have an endpoint in mind, and it’s really hard to know when a work is done. Working with radical emotional honesty and vulnerability, at some point the construction starts to emit either an energy or a feeling or a sense of something. I have made some works that clearly speak of the extent of hard work and labour that has gone into them. I think maybe I stop when I can feel something through the work, something that emitted emotion.

I have a strange relationship with "finished works". I very often think a work is finished, I may even take it to be framed. And then I find that when I see it after distancing from it, I invariably start reworking it. Generally radically, maybe even violently. At one point, I unstretched a "finished" painting, cut deep gashes into it and started weaving into the cut canvas. This was my first hybrid weave-painting.

"I am hoping to create networks of support for artist-women and artist-mothers so that we can feel connection and belonging within a larger group, and can be nurtured within."

Can you tell us about the value of women’s labour in your work?

The labour that underlies weaving has become a core element of what my work speaks about. It’s foundational to everything I do in the studio. Upon installation of my work, the strong sense of women’s labour becomes a defining feature of the work. I think that this labour plays a strong role in the exhibition, becoming an active part of what audiences experience. The exhibition becomes a performance of my labour and the women who work with me that one can feel the labour viscerally, in a similar way to how you feel a live theatrical performance.

I think there’s another paradox in what emerges of women’s labour through weaving. On the one hand, women’s labour is dreary, stuck, contained, and brain-numbing in the way that cleaning a house or doing laundry endlessly can be. It is one way in which patriarchal society has trapped women to contain our power. And then, contradictorily, women’s labour is also repetitive in a meditative, restorative, calming and healing way. My creative methodology is framed within the mode of caring that defines woman/motherhood – that contradiction between nurturing and extending. It guides my way of working in my studio, guiding how I nurture my materials and listen deeply to them.

My work celebrates women’s labour. It puts it on display in the most magical way. It exalts in being a caring, nurturing mother.

You recently completed your MA and have exhibited in Hong Kong, Senegal, Portugal, Cape Town, Paris, London, Lisbon and New York. How has your practice changed over this time?

I am so grateful to my gallerist Julie Taylor of Guns & Rain for opening these incredible opportunities to me. Taking the global stage has made me very conscious of my voice as an African and a South African woman who stands proudly and powerfully. I think about my contribution to global conversations around art, around the place of Africa in contemporary art, and about my responsibility as an ambassador for South Africa. Am I an artist, or an African artist? Am I an African woman artist, or an artist-woman-mother-African? Being on an international stage has motivated me to raise my game. I am focusing on refining my practice, being more rigorous with myself, and asking harder questions of myself while leaving even more time for play and experimentation. Where does my work fit in, and where does it make its own unique path?

How does the venue come into play when you exhibit these tactile installations?

I had a very complex engagement with Origin’s space and installing became a real multi-faceted conversation with the space. I reinstalled the show five times before I felt that it worked. The space is so beautiful, yet so assertive and strong. I’ve had to work with the physical architectural characteristics of the space like its scale, concrete finishes, prohibition on drilling, lighting, windows, and aircon vents, but also with its spiritual and conceptual framings. At moments, I considered the space as a control structure against which my work must rebel, the university as the site of Western knowledge-making structures that must be disrupted. At others, I frame the space as a meeting point that resuscitates indigenous and spiritual knowledge and is thus to be celebrated. The Origins space could be considered as the cold, hard masculine that needs softening by the feminine. All of these framings have entered my mind while working with the space. My ending point was asking how to use the space as a friend that doesn’t overwhelm the work.

In a formal sense, I have worked to acknowledge the space, using its lines and rectangles to frame my work. And then using the rectangular forms of my work to highlight the architecture of the space. But I’ve also worked against the space, aiming to disrupt and soften it by throwing textiles over its hard, concrete overhangs, pretty wildly in places.

Another strong element of the Origins space is the play between light and dark areas, and the changing light through its windows. These had a huge impact on curating the space, and even on one’s experience in the space as the day shifts. You can really feel the passage of the day through the light in the space.

What are you hoping participants take away from the important conversations women are having at Origins Centre's Creative Gatherings this month?

My impetus for taking on this massive task came from recognising the incredible and supportive network of collaborators, mentors and friends that I have who have guided my learning and growth as an artist. The gatherings emanate from my desire to expand this support outward. I am hoping to create networks of support for artist-women and artist-mothers so that we can feel connection and belonging within a larger group, and can be nurtured within.

The response to these gatherings has been heartening. I think it shows that there is a real need for artist-women and artist-mothers to create communities that are supportive and where our interests align, even when the perspectives we each bring are different. I am hoping that exposing shared experiences will help artist-women and artist-mothers feel heard and less lonely and that they have people to turn to when they need help or advice.

The arts is a hard industry for mothers (parents) as so many opportunities require being away from home at night or on weekends for openings or having extended stays overseas. The arts industry in South Africa is also pretty ageist (for example, you must be under 35 to enter certain art prizes). So it’s easy to be overlooked and forgotten, especially if you can’t attend openings.

I’m hoping that as artist-women and artist-mothers we can stamp our mark and assert ourselves as fantastic and thoughtful artists who bring a whole range of art and life experiences with us. That we demand recognition for making work that is rich, layered, textured and thoughtful in interesting ways precisely because of the life experiences we have.

Maybe this is my rebellion against the South African cult of the shiny young thing; the flavour of the month. I think that to sustain a career in the arts, you need wisdom and experience. The gatherings are a shout-out to artist-women and artist-mothers who have both the wisdom and the experience.

Your work is exhibited at Origins Centre where we learn about the history of early humans in Africa. Additionally, you are represented by a female-led gallery for contemporary African art. It seems like re-weaving m/other has opened up a place of learning for contemporary humans, so, is there consideration of your installation to be a permanent fixture at Origins Museum?

That’s ingenious, I hadn’t thought of that and I love it! We’ll have to ask the museum...

Comments