Born in 1913 in Middelburg in South Africa's Mpumalanga province (then known as the Eastern Transvaal), Sekoto was raised in a missionary family and began creating art while a teenager. After graduating from the Diocesan Teachers Training College in Pietermaritzburg (where he also had the freedom to pursue drawing classes) he spent four brief years working as a teacher before making the brave decision to move to Joburg to pursue a career as an artist.

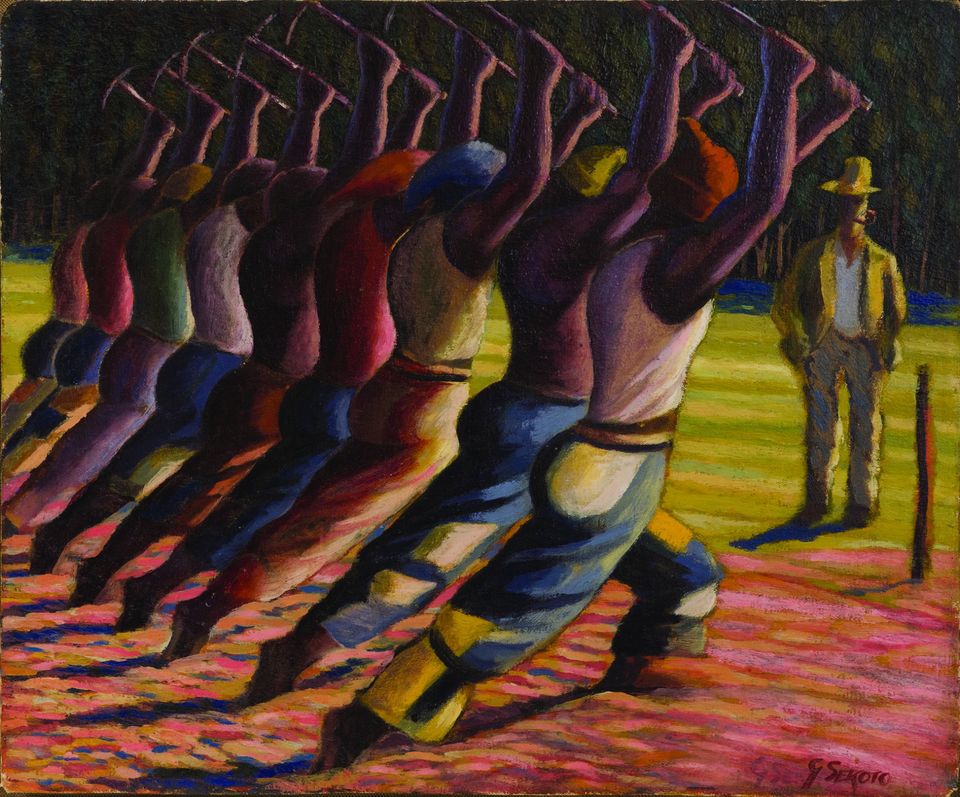

It was in Sophiatown in Johannesburg that Sekoto's career took off. He began experimenting with a graphic treatment of the landscape, juxtaposing bold colours and an expressionist style to vividly portray the street life of this diverse and rapidly changing neighbourhood.

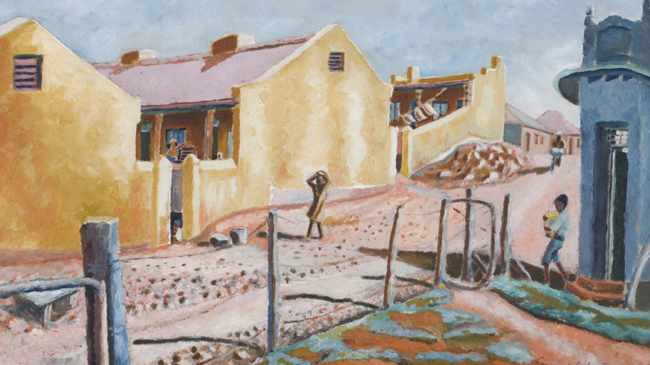

In 1942 Sekoto moved to the colourful District Six neighbourhood in Cape Town and continued to record the vibrancy of black urban life in his canvases, before returning north again in 1945 to spend his final years in South Africa with family in the rundown black township of Eastwood outside Pretoria.

The two years he spent in Eastwood before emigrating to Paris, are regarded as the peak of his career. His colour palette expanded to incorporate vibrant shades and he sharpened his skill for capturing the mood and movement of ordinary scenes. His biographer N Chabani Manganyi remarked that he possessed "a precocious inquisitiveness and wonder" and an uncanny ability to unobtrusively observe his subjects, tenderly capturing their most natural moments.

Sekoto counted among his contemporaries acclaimed painters like Alexis Preller and Walter Battiss and fellow black African artist Ernst Macoba, who left for Paris to further his career in the late 1930s, encouraging Sekoto to follow suit.

While Sekoto was seduced by the artistic opportunities that Paris represented, he also felt that he needed to stay a while longer in South Africa to develop his style. Fellow artist John Koenakeefe Mohl (1903–1985) advised Sekoto to stay in South Africa, arguing that the country needed black artists "who could paint our people, our way of life, our way of living, not speaking in the spirit of apartheid or submission", but eventually Sekoto left to chase his dream.

Sekoto moved to Paris in 1947 and spent the rest of his life there, although the subject of his art remained focused on township and urban black African life. In Paris Sekoto continued to paint these scenes from memory, leaving critics to remark that this later work lacked the immediate realism that made his art in South Africa so iconic.

The artist's first years in Paris proved devastating as he battled the cold, financial hardship, a lack of recognition and a cultural shock compounded by his poor grasp of French. When he had left South Africa he had been selling work at exhibitions but during his first two years in Paris Sekoto sold only five paintings of 25 that he created, plunging him into a deep depression. The lack of financial interest in his art forced him to take up work playing jazz and singing 'Negro spirituals' at the Jacob's Ladder jazz club and he eventually formed a successful music career that supported his artistic endeavours.

Gerard Sekoto spent the rest of his life in Paris and died in 1993, having only finally received the recognition in 1989 that he had long deserved as a pioneering black artist, when he was honored with a retrospective exhibition at Johannesburg Art Gallery and a posthumous honorary doctorate degree from the University of Witwatersrand.

Where to see Gerard Sekoto's work in South Africa

Much of Sekoto's work remains in private collections although there are a few exceptional pieces created during the peak of his career on display at leading South African art museums. Paintings by Sekoto can be admired in the collections of the Javett-UP in Pretoria, Johannesburg Art Gallery, Pretoria Art Museum and at Iziko National Art Gallery in Cape Town,

This feature is part of our ongoing series highlighting the works of South Africa's most celebrated artists. Previous features have included profiles on Alexis Preller JH Pierneef and Vladimir Tretchikoff.

Comments