"Do not be mistaken. The mud walls we are building are not the real house but merely shelter from the sun and the rain. It is you I am building into a walking house."

Known professionally as Helen Sebidi, to know the full title of this visionary South African artist is to begin to understand her nature. Born into a Northern Sotho-speaking community in the village of Marapyane, she is Mmakgabo Mmapula Mmankgato Helen Sebidi. Mmakgabo means ‘keeper of the flame’. Her birth in 1943 marked the end of a long drought in the area, and so Mmapula, ‘mother of rain’, was given to her by the community, in the spirit of hope. The mysterious qualities of water and the pulsating energy of fire manage to coalesce in her familial name, Sebidi, which means ‘boiling’.

Sebidi grew up in what she calls “the rural”, raised by her maternal grandmother in her hometown near Hammanskraal in the then Northern Transvaal, while her mother sought a living in the city. From childhood, Sebidi swam in spiritual waters that nourished her; receiving knowledge about God and her ancestors from her grandmother’s teachings and way of life.

Yet at just 16 years old, she was out on her own in the world. There wasn’t money for her to continue schooling, so she moved from her grandmother’s house to Joburg, looking for domestic employment as her mother had done. The city wasn’t kind to her. She moved from household to household, staying with friends in secret during periods of unemployment, and even spent three weeks in prison after being falsely accused of stealing food. In the throes of the apartheid regime, it was commonplace to be ostracised, prosecuted, and worse, simply for being oneself.

"I was taught that my work should communicate; my work should meet the world."

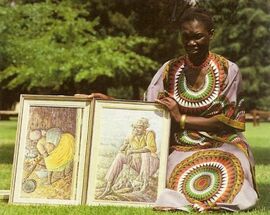

Her trajectory changed when she began working for the family of Heidi Trautmann (formerly Paetsch), an artistic woman in her own right who welcomed Sebidi as a friend. Sebidi would paint in the mornings before work and in the evenings concluding her shifts in the family’s home. “I was working as a domestic worker, but I didn’t know about art. All I knew was to work. I was taught that my work should communicate; my work should meet the world,” she reflects. At Trautmann’s encouragement, she eventually sought formal training under artist John Keonakeefe Mohl in the early 1970s. Mohl was adamant that Sebedi not paint Joburg or Soweto, but tap into her ancestral roots.

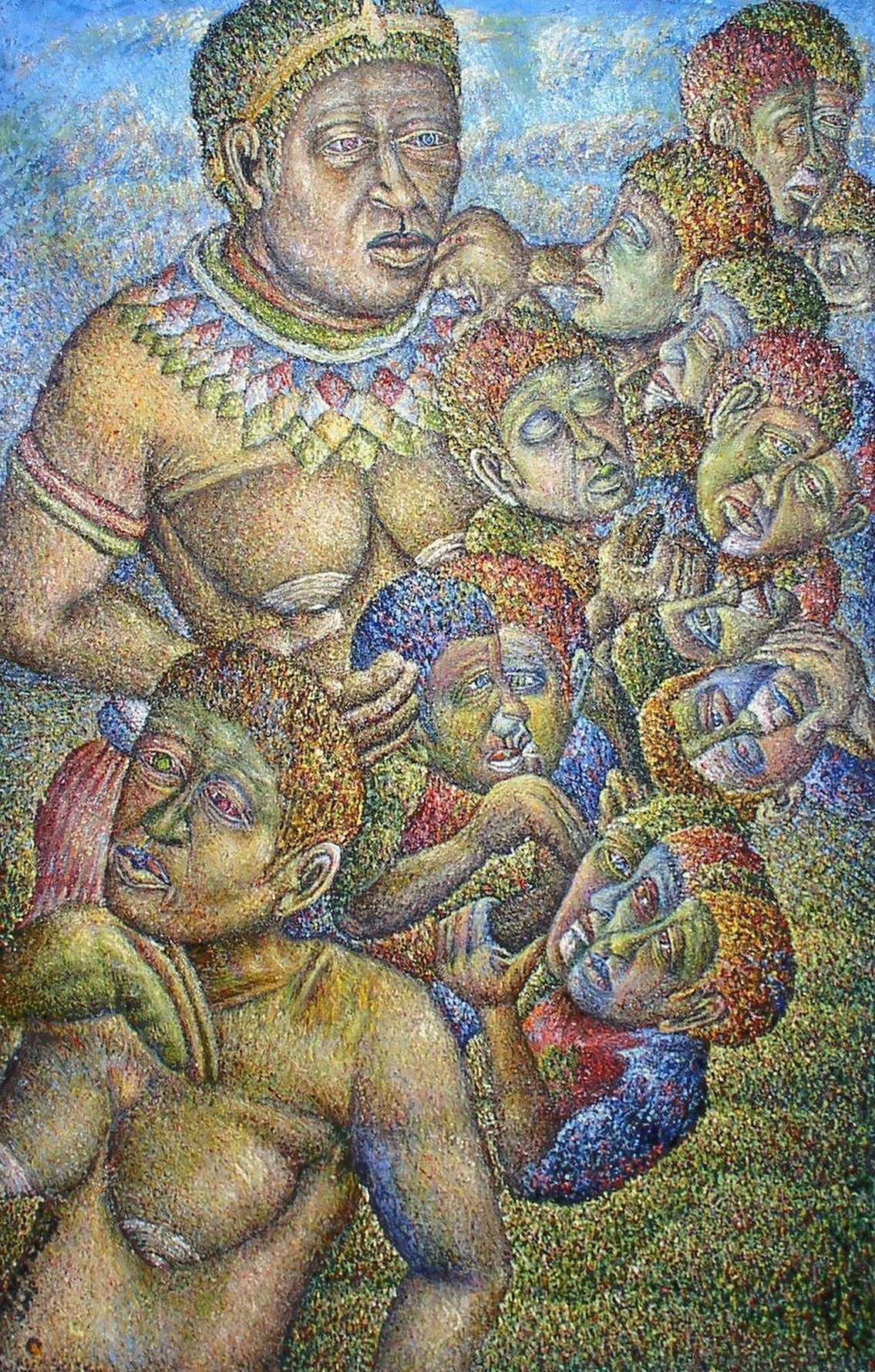

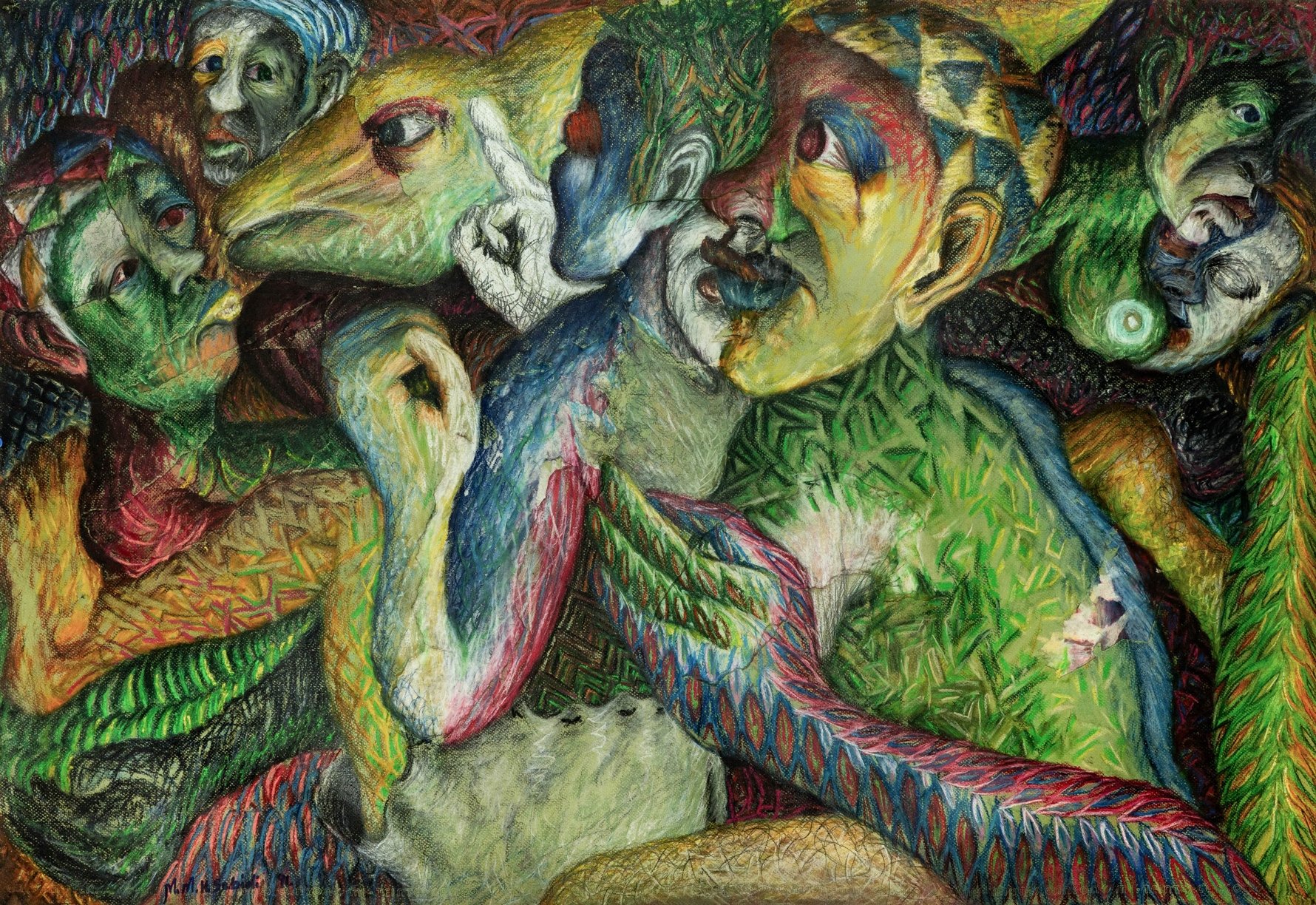

Sebidi inherited her grandmother’s vocational ethic as well as her art. She watched her grandmother build and decorate walls and floors with mud and cow dung, paying close attention to the movements her hands made. Her grandmother was a stern teacher, often undoing young Sebidi’s work. This formative, hands-on instruction found its way into her distinct visual lexicon. Through a chorus of meditative brushstrokes and roaring colours, skin expands and contracts, fires crackle, and waters sway with life in her paintings.

"I wanted to paint straight, the way other people painted, but these textures just came in. Later I said, ‘But yeah, it’s these textures we used to do onto walls and on floors’. I think it’s a blessing that they came into my paintings,” says Sebidi.

In the mid-70s to the early ‘80s, Sebidi returned to Marapyane to be with her grandmother for the final years of her life. In contrast to the relentless pace and raw danger of the city, there she was, able to work quietly without interruption. During this time, the pair shared many conversations about history and spirituality that indelibly shaped Sebidi’s artistic vision.

Sebidi’s career soared after her first solo exhibition with David Koloane’s FUBA Gallery in Newtown back in 1985. But she pays little heed to praise and accolades, regarding them as unnecessary distractions along her life’s path. She simply keeps on working. “I was born for this. I was told the hands were made to work, not to be idle. It’s in my blood. It’s in my spirit. It’s a soul that controls me,” she explains. As the artist sees it, she’s here to teach people to see their lives and understand themselves.

Sebidi lives out the names she’s been given as both a fierce guardian of ancestral wisdom and a trailblazing artist, who sees beneath the surface and has the tenacity to stand it. “We were taught about the deepness of the lake,” she says. “They said you must go deeper in the lake. I’m still searching. You keep up searching, deep down the lake." Her art is magically transformative, singing up life from our nation’s dry bones.

In 1991 Sebidi’s art took her to Sweden, where a collection of her work was to be exhibited. The pieces destined for Sweden were lost without a trace, leaving Sebidi without answers for the three decades that followed. For any artist, a loss of this magnitude would be earth-shattering. Testament to her wild patience, Sebidi was determined, but not deterred. She went on searching and kept up painting. And she absorbed the lesson.

“I was born for this. It’s in my blood. It’s in my spirit. It’s a soul that controls me.”

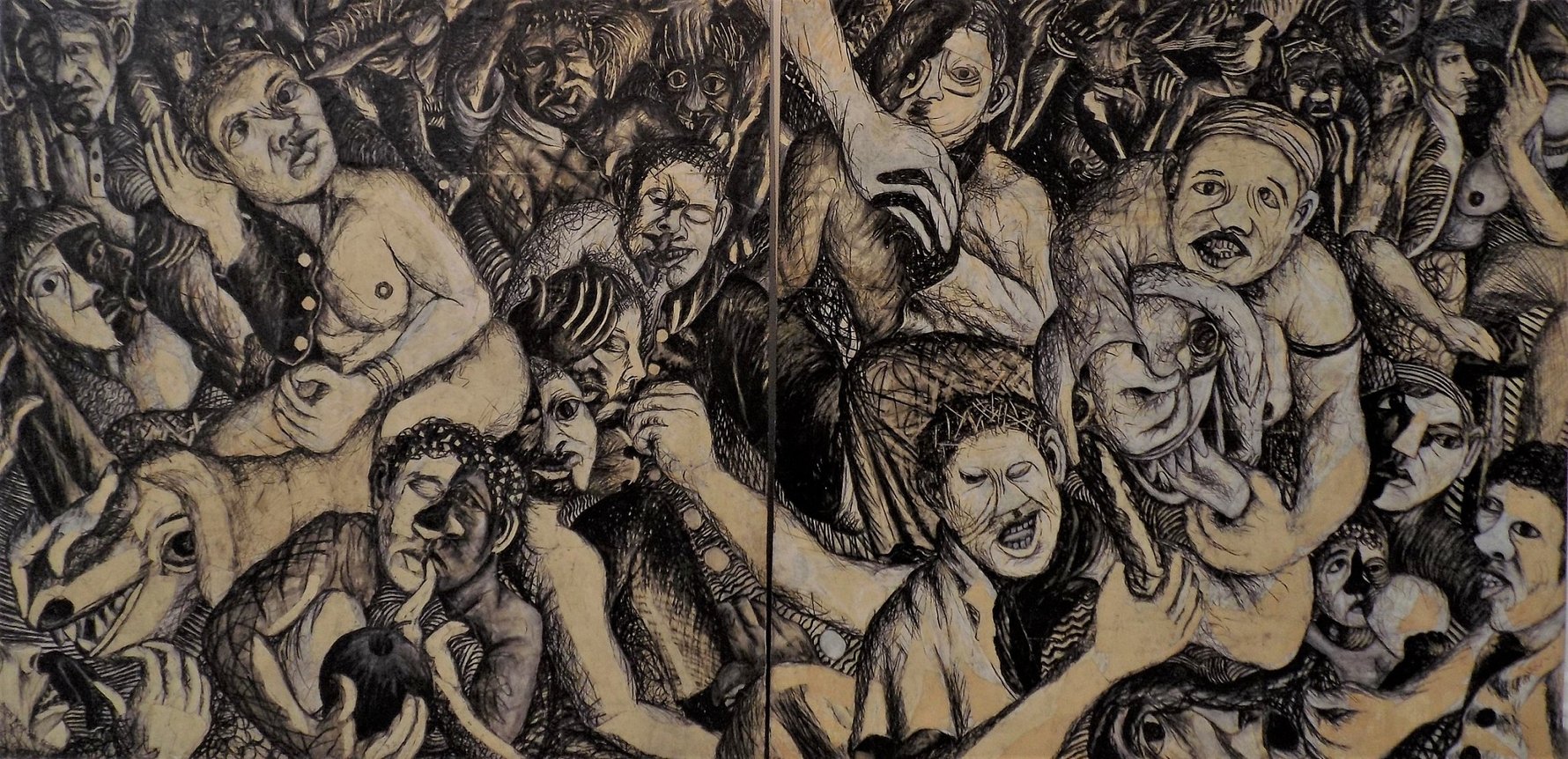

Recently 28 artworks were found in the attic of the Nyköping Folk High School where Sebidi was based during her time in Sweden, and have now been returned home. They will be shown for the first time at UJ Art Gallery in the triumphant retrospective exhibition, Ntlo E Etsamayang (The Walking House).

Speaking to the show’s co-curator, Gabriel Baard, Sebidi says “I feel that [the artworks] were hidden for this communication to be extended.” This suggests, as Baard notes, that if her works had been exhibited and returned to her in 1991, they would have been sold and the communication ended. Says Baard, "This body of work, brought into the world just before the dawn of our democracy and returned 30 years later, is a portrait of humanity in a kaleidoscopic montage of political turmoil, and lost for three decades. It represents a moment of antipodal communication frozen in time that is perhaps more poignant today than ever.”

With South Africa’s next general elections round the corner in May 2024, the profound disillusionment with the state of our nation, 30 years after our first democratic vote, is palpable. Even when she was creating at the height of apartheid, Sebidi’s work never fit the parameters of resistance or protest art. Nevertheless, her art rouses that which is most ancient and enduring and offers a vision for the future. The path is not linear. It necessitates looking back to move forward and is unique to each of us.

"Together, through sweat and blood, you will master every conceivable challenge."

Echoing the words of her grandmother, which have been a guiding light for her, Sebidi says, "Do not be mistaken. The mud walls we are building are not the real house but merely shelter from the sun and the rain. It is you I am building into a walking house destined for where our sun sets and rises to houses that, like you, are built from hard labour. It is here you will knock on the door of each house and be received. Together, through sweat and blood, you will master every conceivable challenge."

Ntlo E Etsamayang (The Walking House) shows at UJ Art Gallery (on the university’s Kingsway Campus) from Sat, Apr 6 to Fri, May 17. The UJ Art Gallery will be hosting five guided walkabouts of the exhibition on Wed, Apr 10, Sat, Apr 13, Sat, Apr 20, Sat, May 4, and Sat, May 11. Each walkabout will be accompanied by a guest. Book your spot here.

Comments