The FACTS: The History of St. Martin & Poznań

Well, the regional treat you can’t seem to get away from is an indispensable part of St. Martin’s Day festivities taking place on and around November 11th. While the rest of Poland (including Poz) is dutifully celebrating Polish Independence Day (a national bank holiday), Poznań also puts a lot of extra energy into observing St. Martin's official feast day on November 11. Also known as 'Martinmas,' the holiday is not a Polish invention; in fact, celebrations of St. Martin's feast day have been been around since the Middle Ages, spreading from France outward, and are still observed in some regions of Europe (though perhaps not with the same zeal as here in Poznań).Poznań's unique focus on the figure of St. Martin is due to the city’s long-standing association with the fine chap, which dates back to at least the 12th century. Documents from 1132 reveal that the Church of St. Martin (the exact erection date of which is unknown) was the only parish on the left bank of the Warta River at that time. A settlement soon grew around the premises, becoming known simply as St. Martin, and was absorbed into Poznań in the late 18th century; today this area is in the very centre of modern Poznań, making St. Martin's Church the most historic church not located on Poznań's Ostrów Tumski.

A reminder of downtown Poznań's days of being known as the settlement of 'St. Martin' is St. Martin Street (ul. Święty Marcin), which today stretches from the Hipolit Cegielski Monument just minutes south from the market square, all the way to Rondo Kaponiera in the west. It's along this approximately eight-block urban stretch that you'll find - aptly enough - today's iteration of St. Martin's Church still standing proudly despite a turbulent history of invasions and fires, the Imperial Castle, Poznań Philharmonic and the Adam Mickiewicz University.

The FESTIVAL: St. Martin's Day in Poznań

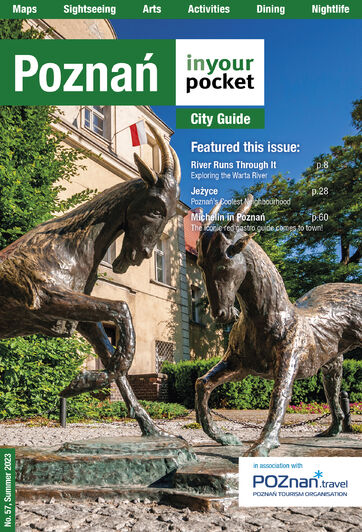

It is this street that sees a colourful annual parade celebrating Martin’s big day. Resurrected in 1994 by the Zamek Cultural Centre and officially named ‘St. Martin Street Name Day,’ the festival starts with a high mass in the aforementioned St. Martin’s Church. Afterwards, St. Martin himself, dressed in a Roman legionnaire’s costume and mounted on a horse, heads a colourful procession up ul. Św. Marcin to the square in front of the Zamek/Imperial Castle. There, the mayor of Poznań hands Marty the keys to the city, marking the start of the celebrations involving a street market with variable levels of kitsch (and critically high levels of croissants), special exhibitions, concerts, and performances inside the Zamek.

The FLAVOURS: St. Martin's Croissants

Just how old is this rogale baking tradition? Well, the oldest advertisement for rogale świętomarcińskie has been found in an 1860 newspaper, but their history should perhaps be traced to pagan times, when oxen were sacrificed during the autumn holiday to please/appease the old Slavic deities; if cattle were lacking, enterprising worshippers used horn-shaped pastries as a substitute. Meanwhile, a popular legend places the start of rogale in 1891, when the parish priest of St. Martin’s Church urged the richer parishioners to help the poor as winter approached; a baker by the name of Józef Melzer prayed to St. Martin for ideas and turning to the street was inspired as the horse carrying the saint in the annual St. Martin's parade slipped a shoe – hence their crescent shape.

On St. Martin's Day, rogale are ubiquitous around town, but if you've missed his feast day, fret not. The pastry's marvellous popularity means that it can be found year-round in certified bakeries. Look for the prominently-displayed blue PGI symbol in the windows of local 'cukiernia' or 'piekarnia' shops, but don't be surprised if they are all sold out by early afternoon. Outside of November 11, St. Martin's croissants are typically sold by weight, and you might be a bit shocked by the prices as a single one of these hefty treats can cost 10-15zł. Once you've tasted one, however, you'll be hooked. This is ain't no pigeon food, but rather one of Poland's best baked delights, bar none.

For those craving a more in-depth experience (and the chance to bake their own rogal), year-round St. Martin’s cheer is available at the city’s Croissant Museum, which has recently made a home for itself right on the Main Square.

The FELLOW: St. Martin Himself

St. Martin and the army were not a good match; having a distaste for bloodshed and violence, the young soldier refused to fight in a key battle, even volunteering to go unarmed in front of the troops when his superiors charged him with cowardice. Luckily for the suicidal conscientious objector, the battle never took place, and a kick in the pants sending him right out of the army was the most severe consequence.

Freed of his duty, Martin made his way to Tours (then known as Caesarodunum) and became a disciple of Hilary of Poitiers, a proponent of Trinitarian Christianity that was at odds with the Arianism of the day. After adventures including confronting the devil, converting most of his family and the entirety of a random Alpine brigand to Christianity, and getting expelled from Milan by the Arian archbishop, Martin finally settled down to establish a hermitage that eventually became the Ligugé Abbey.

Some years later, Martin was obligated to drop his largely hermit-like existence when the people of Tours positively insisted that he become their bishop and would not take no for an answer; according to the most probable account, the preacher was tricked into travelling to Tours to minister to a sick man, but instead was dragged into the church and consecrated. As bishop, Martin continued to sow Christianity among the Druidic heathens, destroy pagan temples, and promote the interests of the Church at the Imperial court in Trier until he passed on in 397, his grave becoming a pilgrimage site drawing throngs of devotees throughout the Middle Ages.

The FEAST: St. Martin's Goose

One particularly humorous and oft-repeated story about St. Martin tells of how he hid amongst some geese inside a barn in order to avoid those trying to press him into service as their bishop. The startled poultry betrayed him with their plucky honking and he was rather embarrassingly found out. With Christians traditionally beginning a 40-day period of fasting ahead of Christmas Eve on St. Martin’s Day, the night before - St. Martin's Eve / November 10th - sees excessive feasting, and the story of Saint Martin and the geese has been conveniently used to justify roasting the plump poultry at this time of year. Across the country you'll see 'St. Martin's goose' (Gęś św. Marcina) popping up on the menus of traditional Polish restaurants in November. Poznań does it best, of course, with their official ‘Goose for St. Martin’s Day’ food festival, during which participating restaurants serve goose dishes for an entire month beginning on the Friday before St. Martin's Day (Nov. 11th). Dig in.

Comments