Indeed, it was a mercurial rise for Katowice once the ball got rolling, and the mills and drills got churning. A relatively remote outpost of 100 homes, Katowice exploded into a prosperous industrial town when a railway link was added in 1847, receiving official city status shortly thereafter in 1897 (still some 700 years behind nearby Kraków). Following Germany’s defeat in WWI just twenty years later, Upper Silesia was left on the fence between Germany and Poland thanks to the unhappy cohabitation of an equal number of Poles and Germans in the area. With both countries vying strongly for the resource-rich region, the Treaty Of Versailles shrugged its sloped shoulders declaring it would be put to popular vote in two years’ time. That was long enough for two Silesian Uprisings to break out in favour of the area’s incorporation into the Second Polish Republic, with a third occurring just after the tardy plebiscite. The League Of Nations, scarcely reading the results, had seen enough violence and split the region down the middle, with Gliwice and Bytom falling on the German side and Katowice becoming part of Poland. Then something unprecedented in European legislation occurred (hold your breath)...

With the now-Polish half of Upper Silesia centred around Katowice constituting a new Polish province, the Polish Parliament in Warsaw passed an act on July 15th, 1920 giving the Silesian Voivodeship almost complete autonomy – a situation unique to any other province in PL. The new province would be entirely independent in its affairs, with the exception of foreign and military policy, and would have its own chief legislative body and treasury. Suddenly, having only received designation as a city 23 years prior, Katowice was promoted to the rank of Silesian capital and had its own Parliament. Boom, just like that.

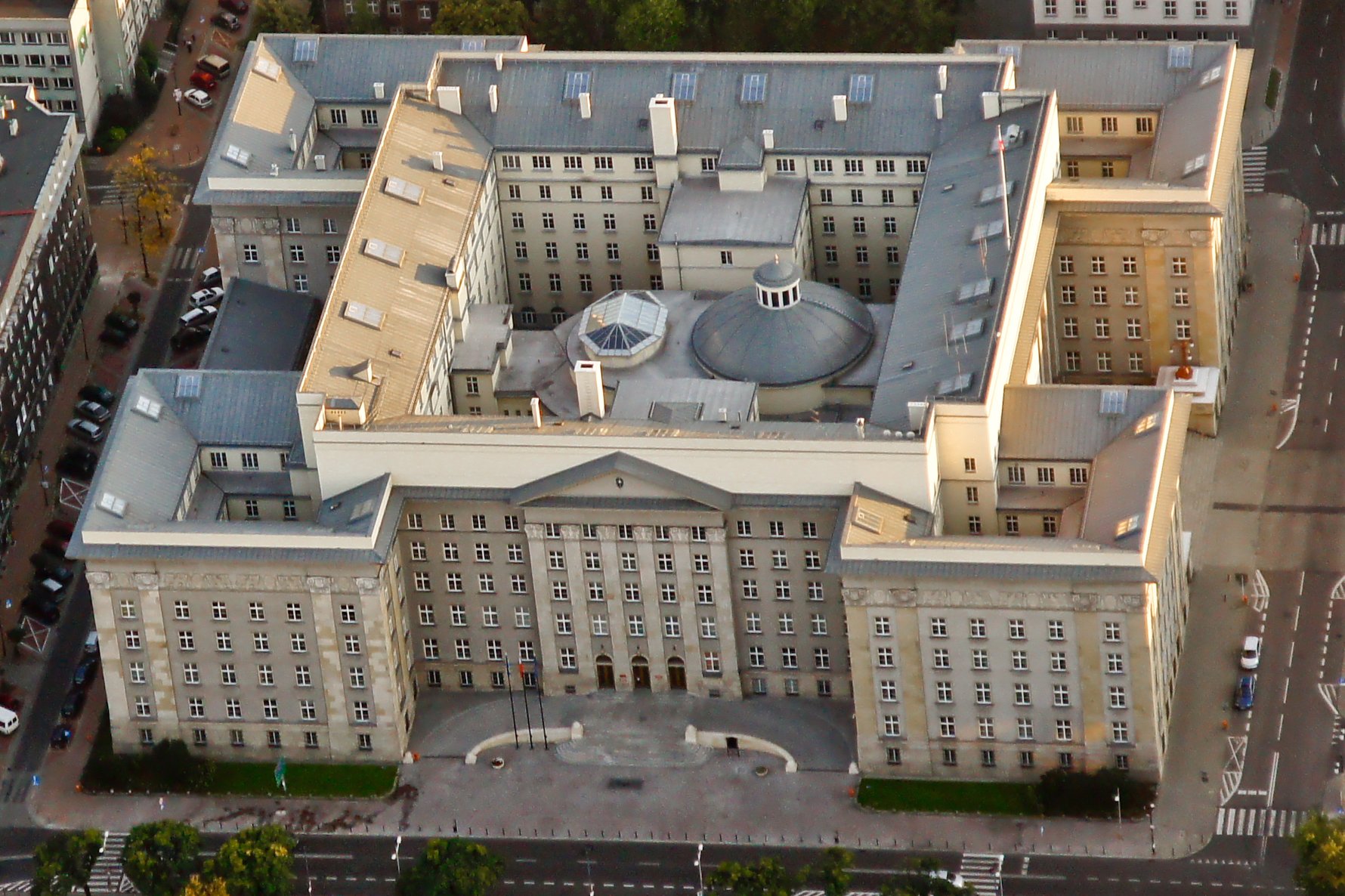

After the fireworks fizzled and the champagne was flat, one of the first resolutions of the new Silesian Parliament was to build itself a Parliament complex in Katowice’s centre where future Parliament resolutions could be passed and pizza parties held. Choosing the project of Kraków-based architects P. Jurkiewicz, L. Wojtyczno, K. Wyczynski and S. Zelenski, the Silesian Parliament building was completed in 1929 , and the government moved in after spending its first seven years in the former Royal School of Building Crafts on ul. Wojewódzka . The new complex covered an entire city block between Jagiellońska , Reymonta , Ligonia and Lompy streets, and was the largest structure in Poland until Stalin built that big thing in Warsaw in 1955.

Consisting of a monumental four-wing main body housing the classical assembly hall, the western side incorporates the main entrance leading to a grand domed vestibule reminiscent of a Renaissance palace decorated with the coats of arms of the towns represented by the autonomous Silesian province. More monumental buildings were erected alongside the Parliament building in the 1930s, emphasising Katowice’s importance as province capital. Among these were the House of Non-aggregated Offices on Silesian Parliament Square , the Syndicate of Polish Iron Works on ulica Lompy and the original building of the Silesian Museum on ulica Jagiellońska (demolished by the Nazis in 1940).

The inter-war period was a true golden age for Katowice, with the Autonomous Silesian Voivodeship clicking on all cylinders. Silesia was the wealthiest and most developed of all the Polish provinces , thanks to its rich natural resources, numerous coal mines and steelworks. Despite the province’s small size it was also one of Poland’s major food producers with a highly efficient agricultural industry. Its population density and rail density were also the highest in the country. Ironically, after all the ‘what country are we in?’ confusion following WWI, less than a decade later a 1931 census claimed 92.3% of Silesia’s population identified Polish as their mother tongue, making the province the most ‘Polish’ in Poland. Just as surprising (and suspicious) given its blue-collared, black-fingernailed workforce, Silesia had the lowest illiteracy rate in the country at just 1.5% compared to the national average of 23.1%. Further evidence of Katowice’s forward march was the erection of