In the late 19th century Poland was suffering a little bit of a crisis: it didn’t exist. At least not on the map, anyway. The backwards-glancing oeuvre of the nation’s art establishment, in its effort to build and bolster the Polish national identity during the time of partitions had succeeded merely in lodging a national complaint, and its influence in European art circles was approximate to a bouquet of dead roses. However, when Polish artists caught ahold of the Art Nouveau wave that was sweeping across the continent in the last years of the century, a much-needed dose of modernity and style were injected into Polish culture resulting in perhaps the country’s most brilliant modern artistic epoch. Wider in scope than its European counterparts, Poland’s Młoda Polska (‘Young Poland,’ 1895-1914) movement set about revitalising all of the arts - painting, poetry and music as well as architecture and design - in a rejection of the mainstream bourgeois tastes of the day.

Despite being considered the Austrian province of Galicia’s second city at the time, to more cosmopolitan Lwów (today Ukraine’s Lviv), it should come as little surprise that Kraków was to emerge as the heart of Młoda Polska. Though perhaps most associated today with rather far afield Paris, Art Nouveau owed a lot to the vision of Alfons Mucha whose influence was strong in nearby Prague; meanwhile, in the spring of 1897, Gustav Klimt was co-founding the famous Secession Group in Vienna – a city which Kraków had close political and cultural ties to. As a Habsburg city during the period of Poland’s division, the flow of information and ideas from the Austrian capital was strong and Kraków also enjoyed a more lenient political climate than Polish cities in the Prussian and Russian zones where Polish culture was suppressed more aggressively. Though Austrian occupation was hardly a picnic, the city’s lot improved significantly after 1870 when Galicia was granted autonomy, the Jagiellonian University was again permitted to conduct courses in the Polish language, museums were opened and the Art Academy was born. With a proud patriotic tradition as the former royal capital, Kraków perhaps embodied the Polish spirit more than any other city at the end of the 19th century and artists flocked from across the divided country to contribute to its creative pulse.

As the previous generation of Jan Matejko and his contemporaries had viewed artistic expression as a necessary means of preserving Polish culture and consciousness, so too the new school believed in creative activity as a patriotic and personal responsibility. However, they had imbibed enough sobering landscapes and epic historical paintings, and in the increasingly liberal and rebellious spirit of the times they were pursuant of something a bit more intoxicating. Rejecting romanticism as inert nostalgia, the new movement was more interested in exploring the darker dream world of the unconscious, the symbolic, and both the comic and melancholic spheres of the spirit. Embracing a more bohemian brand of decadence borrowed from Parisian café culture, soon several unofficial headquarters for the movement had been established where members could be found scribbling their new imaginings and manifestos outside the pale of the established academia.

The most important of these became the Lviv Confectionary Shop (Cukiernia Lwowska) at ul. Florianska 45. Opened by Jan Michalik in 1895, the unassuming shop suffered from its close proximity to the art school on Plac Matejki whose close-knit circle of students took over its backroom, much to the irritation of the owner. The story goes that Michalik was so frustrated by their creative vandalism of his shop, he bought them paper, paints, inks and pens in order to save the surfaces of the tables and walls. The gesture only served to encourage them of course and soon Michalik’s shop was filled with paintings and drawings by the city’s most talented young artists, giving it the unshakable reputation of being Kraków’s best bohemian hangout and making Michalik an unwitting patron of the arts.

Among the regulars of Michalik’s sweets shop and café were many who would go on to become some of the most well-known Polish artists of the early 20th century, including Jan Stanisławski, Leon Wyczółkowski and Feliks Jasieński – to whom a permanent exhibit in the Manggha Arts Centre is dedicated. One of the café’s earliest patrons was Stanisław Wyspiański – the painter, playwright and designer who later came to define the movement, remembered today as Kraków’s most beloved creative mind. Apparently Wyspiański once offered to redesign and paint the entire interior of Michalik’s, but the owner turned the artist down assuming it would amount to professional suicide. He would live to deeply regret the decision later.

As the notoriety of the Młoda Polska movement grew, so too did that of Michalik’s sweets shop which became known as Jama Michalika – or ‘Michalik’s Den,’ - the same name it bears to this day. Michalik could no longer begrudge his best guests and the partnership flourished as the group essentially decorated the entire café. Ironically, the interiors were given a full art nouveau makeover years later by one of Młoda Polska’s brightest lights, Karol Frycz, out of his gratitude towards the place.

Zielony Balonik & the Birth of Polish Cabaret

After a trip to Paris in 1905, Jan Kisielewski came back to the group with the idea to start a cabaret modelled on the French capital’s famous Chat Noir. Gathering the rather immense talents at hand, they decided to go for it, naming the troupe Zielony Balonik (‘The Green Balloon’) and putting on their first official performance on October 17th, 1905. With no curtain or stage, the show went on around the same back table where regular happenings occurred, was completely spontaneous, and generally had the atmosphere of a group of friends getting together over a bottle of hard spirits. It was a huge success. Successive performances were better scripted thanks to the sketch-writing talents of Tadeusz Boy Żeleński (whose bust can be seen today in the Planty between Wawel and ul. Poselska), but were still completely unpredictable, outrageous, uncouth and often included the drunken host belittling the bourgeoisie, many of whom were gathered in the audience. In fact, few were safe and one of Zielony Balonik’s favourite targets was the grandiloquence of its own movement. The post-performance parties were always a riot of song and revelry, with the sight of women smoking cigarettes sending a shock into some members of the community. Soon conservative Kraków was a hotbed of gossip alleging orgies and other blasphemous acts were taking place inside Michalik’s; mothers wouldn’t let their daughters look in the direction of the café when passing and pensioners proclaimed the patrons were nihilists. People were paying attention.

In actuality, Zielony Balonik’s weekly shows comprised of satirical sketches, humorous songs and political parodies poking fun at the establishment through the liberal use of wordplay and sarcasm, with the jokes only occasionally turning vicious or vulgar. Its reputation grew and each week Jama Michalika was a full house of merry dignitaries, artists and aristocrats, many of whom came great distances to see the show. Particularly popular were the Zielony Balonik Szopki – absurd and satirical puppet theatre shows which ran from 1906 to 1912. Zielony Balonik was the first Polish cabaret – an art form which would enjoy immense popularity in post-war PL and today - and more so than any art publication or gallery, became the main platform for Młoda Polska. Unfortunately the war would bring its glorious run to an end, but not before making a lasting impression on the intellectual and aesthetic landscape of the city and playing a major role in the national consciousness of the country after independence was restored in 1918. Regular performances came to an end in 1912 and the final performance of the original Zielony Balonik was in December 1915. Michalik was forced to sell his legendary café and moved to Poznań where he died in 1926; he was buried in Kraków’s Rakowicki Cemetery in keeping with his final wishes.

What to See

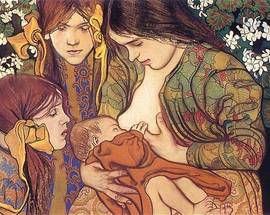

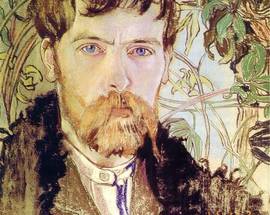

The cabaret and climate of Młoda Polska played a large role in launching the brilliant careers of two of Poland’s most important early-20th century artists, Stanisław Wyspiański and Józef Mehoffer. In fact, Mehoffer’s city-centre mansion at ul. Krupnicza 26 has been beautifully preserved as a portal into those times, full of period furnishings, sketches, and portraits, and it was there in his drawing room that the members of Młoda Polska were frequently entertained (see Józef Mehoffer House). Also of note is the Noworolski Cafe. On the ground floor of the Cloth Hall, this cafe still embodies the spirit of the late 19th century salons, and the interior is full of rich art nouveau motifs by Mehoffer.

Mehoffer and Wyspiański worked together under the supervision of elder Polish master Jan Matejko (whose monument can be found opposite the Barbican) to design 36 new stained glass windows for St. Mary’s Basilica on Kraków’s market square, before Wyspiański went on to one of his defining works, St. Francis' Basilica. The artist’s intricate interior wall paintings celebrate St. Francis’ love of nature with colourful floral patterns, but it is the imposing, almost violently energetic stained glass window entitled ‘God in the Act of Creation’ that undoubtedly makes the biggest impression. Nearby, the modern Wyspiański Pavilion (Pl. Wszystkich Świętich 2) was recently built specifically to showcase Wyspiańki’s enormous stained glass Wawel triptych, which was deemed too grotesque and controversial at the time of its creation, and therefore never installed in Wawel Cathedral. It is this work, however, that perhaps best exemplifies the visual aesthetic of the Młoda Polska movement. The three figures depicted are martyred Polish heroes St. Stanisław (on the left) and Henryk Pobożny (on the right) - shown Christ-like at the moment of their deaths, while Kazimierz the Great's bare skull bears the royal crown between them.

Almost unknown even to locals, Wyspiański designed one other large-scale stained glass window in Kraków before his premature death in 1907 at age 38, at the height of the movement and his own success. One of the city’s best kept secrets, ‘Apollo: the Copernican Solar System’ lies hidden in the Medical Society House at ul. Radziwiłłowska 4 unseen from the outside on this obscure street near the train station. Though the building is not open to the public, name-dropping the artist should be enough for the guard to let you in to have a brief look at this majestic window at the top of the stairs.

Though the subject of great attention in Kraków, particularly the collection on the top floor of the main branch of the National Museum (before which stands a huge monument to Stanisław Wyspiański) and to lesser extent the 19th Century Polish Art Gallery in the Cloth Hall, the best living museum of Młoda Polska today remains the Jama Michalika café. Though the brightly-dressed babcias and tourists that gather here today are hardly ambassadors of the avant-garde, the historic legacy of the space has been well-preserved. Hours could be spent examining the framed pre-war caricatures, paintings and illustrations that still line the walls, exclaiming over the famous (to some at least) signatures doodled in the corners. The original marionettes of the cabaret can be found in several display cases, there are some splendid stained glass pieces and you might even play a few bars on the piano that still graces the famous back room of Karol Frycz’s incomparable fin-de-siecle interior. The obligatory cloakroom (1 złoty, please) and stubborn smoking section prove that this place has made no attempt to modernise, and must be regarded as one of Kraków’s most priceless and authentic establishments.

Comments