The Polish Government were therefore determined to build a new seaport at the top of the ‘corridor’ and the place they settled on was the small fishing village of Gdynia. The development of Gdynia into a major port was seen as critical for the economic independence of the new country and the story of this development was to reflect, not just one of the most incredible building projects of all time, but also the determination of a nation and its people to survive and to flourish in a new era of European history.

The Development of Gdynia

Although Gdynia had first appeared in records in 1253 as a small Kashubian fishing village by 1789 it had only increased in size to a settlement of a mere 20 houses. About 80 years later, as the West Prussian village of Gdingen, it had developed slightly, with a recorded population of around 1200, some restaurants and accommodation for holidaymakers. But it was as part of the new Poland that a plan was put in train in 1920 to transform it utterly, a plan which was accelerated by the passing in the Polish parliament (Sejm) of the Gdynia Seaport Construction Act in 1923.

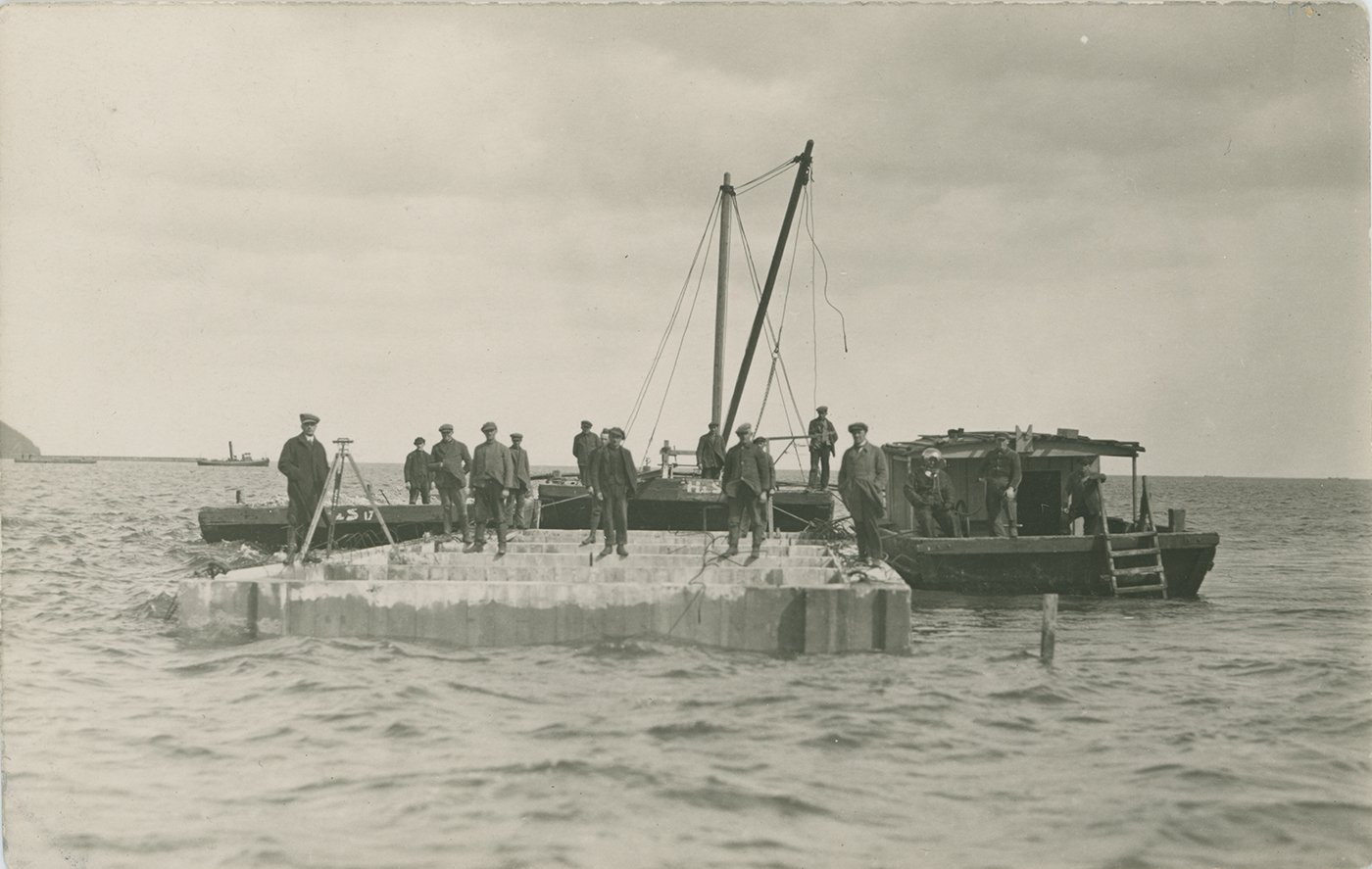

The new port to be carved out of the Baltic coast was to be located in this former fishing village: the Hel Peninsula provided protection from strong winds, the sea in the area was deep and usually free of ice in winter, and an existing railway was just 2 kilometres distant. Under chief port designer Tadeusz Wenda, building of the port began in 1921, but financial problems caused delays and, in 1922, the Polish Parliament decided to light a fire under proceedings. By 1923, Gdynia had a small harbour, a 550-metre long pier and a wooden breakwater, and the port was visited by its first major ocean-going vessel and its first foreign ship, the French Kentucky.

In late 1924, the Polish government engaged a French-Polish consortium to build a harbour with a depth of seven metres, and by the following year Gdynia had gained further piers, a railway and cargo-handling equipment. However, work continued at quite a slow pace until 1926 when Polish exports increased during a German-Polish trade war and as a result of a British miners’ strike. By late 1930, docks and industrial facilities had been built, and the port was finally connected to the Upper Silesian industrial and coal-producing centres by the newly constructed Polish Coal Trunk Line railway. Poland’s first passenger shipping line, from Gdynia to New York, also started up and over subsequent years famous ships like the MS Batory and MS Chrobry were to link Gdynia with transatlantic locations.

While the port was being constructed, so too was the city. City rights were granted on February 10, 1926, at which time Gdynia had around 6,000 inhabitants and the city started to expand quickly with the Polish government alone bringing about 50,000 citizens to the city. By 1939 the population had risen to over 120,000. While the port was built by the state, essentially the city was built by private investors. Small single-storey buildings were initially constructed, then these were demolished by the owners to make way for multi-storey buildings as the city grew and the inhabitants became more prosperous. The project attracted all parts of Polish society to the coast with engineers, construction workers and administrators all relocating from other Polish cities, in particular Warsaw, to take part in this vital national project.

The construction of the basic harbour was completed in 1935 and by 1938 the former fishing village had become the biggest and most modern port and shipyard on the Baltic with almost half of Poland’s trade passing through it. Yet, disaster was soon to follow.

Gdynia during WWII

Following the shelling of Westerplatte on 1st September 1939 and the start of World War Two, German troops captured Gdynia less than two weeks later. As part of the Nazi's policy of 'Germanisation', the city was renamed Gotenhafen (literaly 'Goth Port') after the ancient Germannic tribe that had inhabited the area. Among name changes to streets and other landmarks, Skwer Kosciuszki was renamed Adolf Hitler Platz. The Poles brought by their government to the city of Gdynia were expelled and worse, around 12,000, especially the more educated, were executed. The port was turned into a German naval base and the city was also used as a sub-camp of the Stutthof concentration camp near Danzig.

Photo by Hans Sönnke, Attribution - Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-E10457 / CC-BY-SA 3.0

Nazis built in 1940. After the Soviets took over in 1945, the facility was stripped of essential

materials and was abandoned.

Other German troops and civilian refugees retreated to the headland at Oxhöft (now the suburb of Oksywie), from where they were evacuated to the Hel Peninsula. The city was finally taken by the Russians on 26 March 1945, begining the Communist era of Gdynia and Poland.

Post-War history

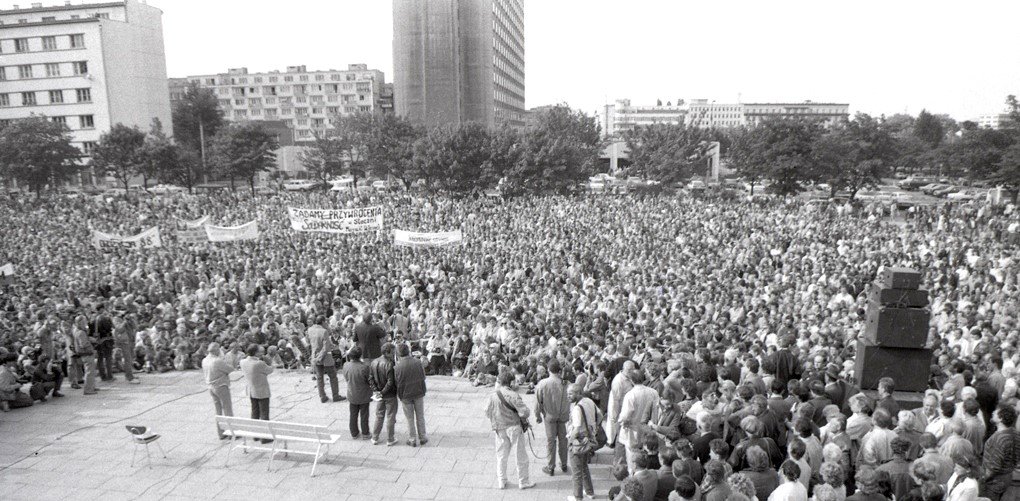

Having built this port and city from scratch, the post-war Polish state reverted the name Gotenhafen back to Gdynia and started the process of making the port once again a major location for importing and exporting. The shipyard produced a large number of ships, many of them for the Soviet Union, but is perhaps best known internationally for the role the shipyard workers played in the formation of the Solidarity trade union. An earlier event, in 1970, which left much bitterness, had seen demonstrating Polish shipyard workers fired on by the police, leaving at least 20 people dead (see our articles on Janek Wiśniewski and Monument to the Victims of December 1970). To this day this is one of the more tragic events of the fight against the communist authorities and its memory has been somewhat overlooked by the events of 1980 which saw Gdańsk recognised as the spiritual home of the anti-communist fight. This is something which still rankles to this day with the local population who feel that the major contribution and the price paid in human life by the people of Gdynia has been forgotten.

The momentum of Solidarity would ultimately carry over to its neighbouring countries and, in 1991, the Soviet Union collapsed. Like the rest of the country, Gdynia has enjoyed an increase in the standard of living and the economic prosperity brought in from the European Union. The city's population, however, has tapered off in growth. It sits just shy of 250,000 souls and has barely increased in the last 10 years. The observation of many expats is that the residents of Gdynia don't want to see the city become dense and overcrowded like others in Poland. There is also a push to prevent the forest areas in Redłowo and the Tri-city Landscape Park from being developed. For this reason, many districts of Gdynia are perfectly integrated with natural surrounds.

If you choose to visit the city, take a moment to remember that had it not been for the Treaty of Versailles and the Poles’ determination to show the world, and in particular their bullying neighbours that they were worth their salt, this place might be something quite different altogether today.

What to See in Gdynia?

The city centre is considered to be very well planned, with ul. 10 Lutego/Skwer Kosciuszki and ul. Starowiejska forming the primary west-east axis and ul. Swietojanska and ul. Abrahama the north-south one. For obvious reasons, don’t expect to find an old town here, though there are still some buildings from its days as a small resort. Most notably, Domek Abrahama is a cottage built in 1904, where Kashubian activist Antoni Abraham lived and is now a restaurant. If it's history that you're interested in, the City of Gdynia Museum will give you a good grounding. The Naval Museum next door, featuring a garden full of weaponry including a rusting MiG fighter, is also worth a visit if you have children in tow. Finally, one of the Gdynia's biggest attractions is the Emigration Museum residing in the rennovated Dworzec Morski (Marine Station) in the shipyards. The exhibition is a fascinating look at how, why and to where millions of Poles have emigrated over the centuries and, in the last century, many of those individuals departed Poland from the port of Gdynia.

Young travelling families should note that there are a number of places in this demographically-young city worth visiting that your children will love! Down on the waterfront is the Aquarium, which has a collection of marine life from all over the world and features residents from the Baltic as well! Catch a train to Gdynia Redłowo and visit the Centrum Nauki Experyment, an interactive science centre which is fun for all ages. Just across the from the afore-mentioned Naval Museum is the city's the main beach, which also has an awesome kids playground right next to a cafe/restaurant.

We again emphasise that this is a young city and that means the music, arts and cultural communities are very active! The Gdynia Film Festival is the Cannes of Poland and is highly regarded internationally. The city always hosts many events during the Gdańsk Shakespeare Festival. Annual music events like Open'er Festival and Globaltica draws a crowd from all over Poland and further afield. The Red Bull Air Race World Championship, which started in 2014, packs out the waterfront every year. Keep an eye on our Events Page.

Photo By D. Nelke, Courtesy of the City of Gdynia

While the port today is no longer the biggest in the Baltic it is, along with the neighbouring port of Gdańsk, still of vital economic importance to Poland. There are a few different ways to view it. Most picturesque is to take a walk up to one of the viewing points either at the top of Kamienna Góra or in the Pogórze Górne district. The latter is about 15 minutes bus ride from the centre. Take bus 194 from outside the Hala Targowa to the last stop to enjoy majestic views over the entire city and the port. It is also recommended to take the local commuter train (SKM) to the Gdynia Stocznia stop to see the poignant memorial to workers murdered during the 1970 strikes. Finally on the port and Solidarity theme keep an eye out for another memorial to the victims of 1970 outside the City Hall building.

Do look a little deeper as well, for as much of the development of Gdynia took place during the heyday of the modernist architecture movement, there are numerous stylish buildings from that era. The short walk from the main train station to the sea along ul. 10 Lutego and Skwer Kosciuszki will provide the visitor with several examples of modernist architecture which reflect the city’s maritime role, including buildings with portholes, quarterdecks and curved facades to resemble ships. A few quick examples include the Tourist Information office (formerly the Polish Ocean Lines building) on ul. 10 Lutego (at the junction with ul. 3 Maja), the Bank Gospodarstwa Krajowego residential building around the corner on ul. 3 Maja and the Gdynia Aquarium building down near the water.

Further reading

Local photographer and historian, Sławomir Kitowski, has published a number of beautiful albums recording various parts of Gdynia and her history. For those interested in seeing more wonderful photographs of the development of Gdynia from fishing village to international port should keep an eye out for these, pick of which is Gdynia Miasto z Morza i Marzeń (Gdynia – City of the sea and dreams), which can be picked up from EMPiK on ul. Świętojańska 68. You can also access more photos of Gdynia over the years thanks to the National Archive which has made collections available online.

Comments