But we must remember that before South Africa’s first democratic elections in 1994, black artists in general, and resistance artists in particular, in this country were barred from exhibiting their works, prevented from accessing tertiary art education, and omitted from mainstream art histories – and therefore the canon.

Thirty years into our democratic age, some of South Africa's artists are now only enjoying late but no less deserved acclaim during their lifetimes, while others are no longer around to enjoy this.

What is encouraging is that there’s a groundswell of major retrospectives of lesser-known, often repatriated works, that celebrate South Africa’s formerly unsung art heroes. To name a few of many, the import of artists like Gerard Sekoto, Mmakgabo Helen Sebidi, Moses Tladi, George Pemba, Pitika Ntuli, and Esther Mahlangu, who are relatively well-recognised within the immediate art community, is becoming part of the wider cultural conversation.

Mmakgabo Helen Sebidi is indeed one such case, with her exhibition Ntlo E Etsamayang (The Walking House) at UJ Art Gallery. The backstory to the works on show is nothing short of miraculous. Twenty-eight of Sebidi’s artworks went missing in 1991 on their way to an exhibition in Sweden. Now, after more than three decades of grief, unanswered questions, and continued searching, these lost-and-found works are being shown to the public for the first time – and on home soil (read more about this remarkable show here).

This exhibition is a landmark for Sebidi, whose last serious showcase was with Norval Foundation in 2018. Despite her status as a national treasure – she was awarded the Order of Ikhamanga in Silver in 2004 – the transformative power of Sebidi’s works is, at last, coming to the fore. She’s been nominated for an honourary doctorate from the University of Johannesburg (UJ) and, should she accept, she’ll join the company of Esther Mahlangu and Noria Mabasa.

The works in Ntlo E Etsamayang were created by Sebidi during a time of political transition in South Africa. UJ visual arts professor Kim Berman, who co-curated the exhibition, explains their significance for the artist. "This work represents a repository of pain, trauma, and hope that she felt had to be conveyed and witnessed by the world. [...] For many years, the loss of this art haunted Sebidi and contributed to her pain as unfinished business of her life’s vision and purpose. The news that the work was found and its eventual return after 33 years through a series of serendipitous connections has been life-changing for Sebidi. She cried when we told her about their discovery. [She called them:] "My babies, my babies". She was filled with extreme gratitude and determination rather than regret and bitterness. Her purpose could finally be fulfilled."

One can only imagine how Sebidi’s journey may have been different had her works reached their intended destination all those years ago, and were exhibited as planned. Seen through her spiritual framework, the artist believes these works were hidden so that the communication could be extended. Their re-emergence has indeed occurred at a pivotal time, as South Africans prepare to vote in the May 2024 general elections.

Co-curator of Ntlo E Etsamayang, Gabriel Baard writes, "As we stand on the doorstep of 30 years of democracy, many young voters feel this is their 1994. Urged to not only make a change but embody that change, and understanding the importance of these elections as a defining moment in South Africa’s history, I cannot help but see the synchronicities between these moments of change through the lens of [Sebidi's] rediscovered art."

Berman adds, "This is a very important milestone for Mme Sebidi. She has the idea that her works missing for over 33 years were meant to return at this threshold moment in South Africa. The works invite a different kind of listening and have a real potency in this moment."

Correct as Sebidi’s assessment may be, and to her credit, this is a generous viewing. The same cannot quite be said for many of South Africa’s black and resistance artists who began their careers under the apartheid regime and, like Sebidi, are in line to receive the recognition they deserve.

Following the Universities Act of 1958, which prevented artists from studying their craft, many went into exile. "As a result, several daring initiatives, or grey areas, were started, such as the Polly Street Art Centre in the 1950s and '60s and later, the Johannesburg Art Foundation [founded by Bill Ainslie] in the 1970s and '80s, providing study opportunities for those who were excluded,” explains Wilhelm van Rensburg, one of the curators at Strauss & Co doing excellent work to raise awareness around the country's under-recognised artists.

"After 1994, there was a moment in which the focus was on such neglected artists as Gerard Sekoto, Ernest Mancoba, Selby Mvusi, and so on, South Africa was welcomed back into the international arena, participating again for the first time since the late-1960s in the Venice Biennale, and included in many U.S. exhibitions in the late-1990s such as Liberated Voices: Contemporary Art from South Africa. But sadly, a trend not sustained the last couple of decades," van Rensburg tells us.

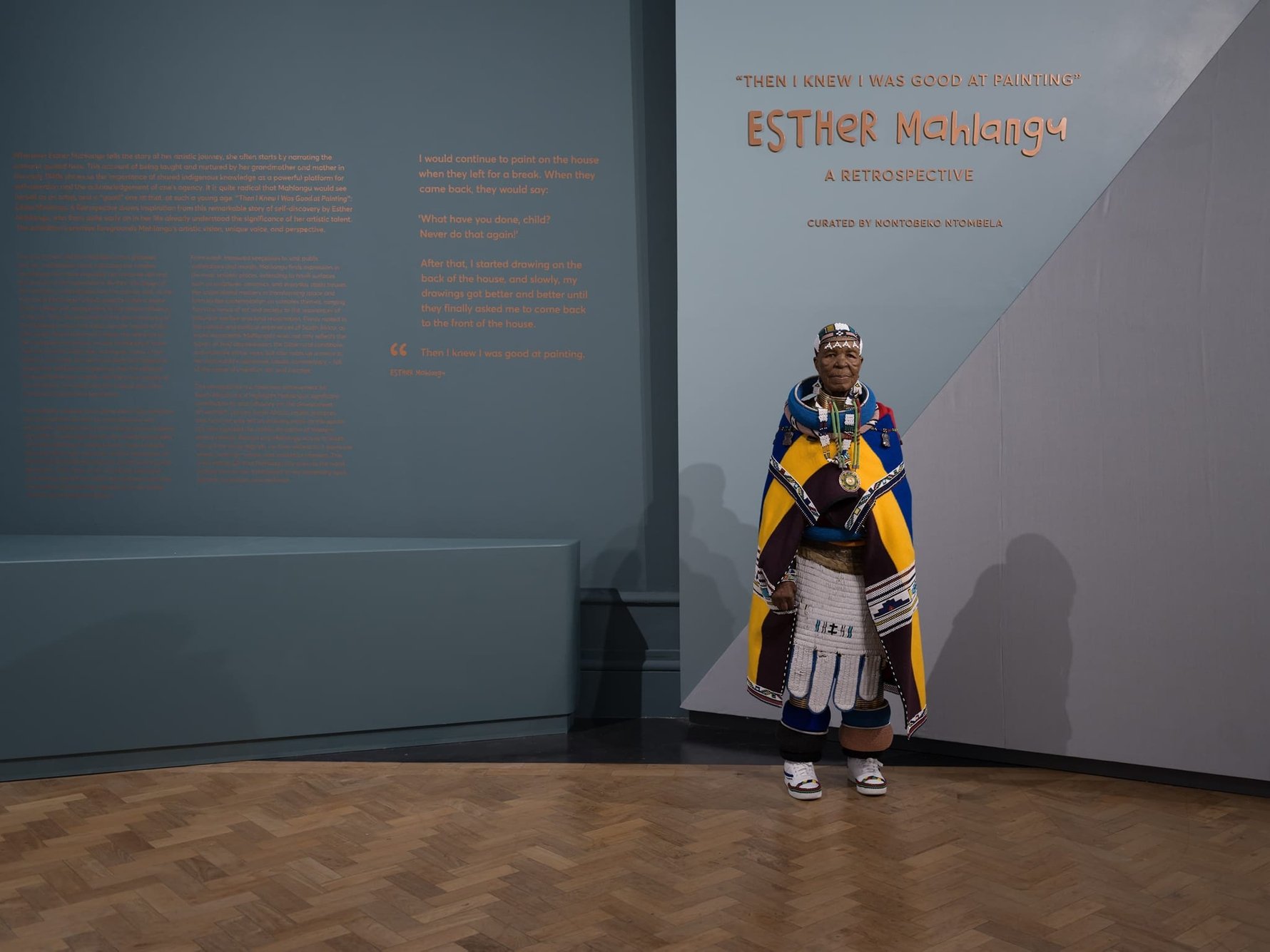

The tide seems to be turning. Alongside Sebidi’s awe-inspiring solo, a broad retrospective for Esther Mahlangu titled Then I knew I was good at painting is being shown at Cape Town's Iziko South African National Gallery, making her one of the few South African artists who’ve had an opportunity to present at a museum in this way. "Dr Mahlangu’s life, work, and vision are not more important now than they have been [previously]. She has been painting for 78 years and has worked extremely hard to achieve global success. What has possibly changed is how South Africa seems to have more recently recognised her valuable contribution as a contemporary artist, and not only as a much-loved cultural ambassador of the Ndebele nation," says Craig Mark, director of The Melrose Gallery.

This moment is ripe for the rediscovery of previously overlooked and forgotten artists. "There is a whole generation of people who are deeply interested in art, but who missed the opportunity to experience the South African art of the late-20th century, and who would look at that art without all the political baggage that sometimes accompanies it," says van Rensburg.

To this aim, Strauss & Co has hosted a series of non-selling legacy exhibitions since 2019 to showcase the work of pivotal South African artists. In 2023, van Rensburg curated a tribute exhibition for Sydney Kumalo and Ezrom Legae, who were at the centre of the Modernist movement, saying, "These two sculptors paved the way for what is known today as Contemporary African Art. Not only in form but also in subject matter, they laid the foundation for a succession of modern and contemporary artists to explore the current state of affairs of the world in and through their art."

Most recently, in collaboration with Kalashnikovv Gallery, Strauss & Co welcomed a commemorative showcase of the late-great Alfred Thoba in the 2024 exhibition True Love. While creating his seminal work 1976 Riots, Thoba had to move all around Johannesburg in search of accommodation and studio space and carried the large painting with him at night to avoid unwanted attention from the police. He's recorded in Sue Williamson's book Resistance Art in South Africa as saying, "I worked very hard on the picture. When I finished I cried a lot. Each time I looked at it I cried. The cops wanted to see it. Luckily the day they came in the picture was covered. I’m sure they were told about it. I had to take it to a certain businessman in High Point to keep it safe for me."

The continued efforts of the Javett-UP Art Centre join these ranks. The 2020 exhibition Shaping the Grain, featuring the work of black South African sculptors such as John Baloyi and Owen Ndou sparked an interesting dialogue around the notion of the unknown artist and the need to not only make the work known, but the stories and experiences of black artists too. And there are other organisations, including the Apartheid Museum and its current group exhibition Resilience and Reflection, supporting repatriation and celebrating South African artists whose work is not only a record of life during apartheid, but a roadmap for our future. It's brilliant to witness.

In Baard's estimation, "This not only seems to be a theme in South Africa but around the world as of late. I think this is a result of a closer and more caring reading of the art, which has allowed for potential gaps or under-acknowledged individuals and groups to be celebrated." South Africa's artistic inheritance isn't a simple one to navigate but, as Sebidi's exhibition so poignantly illustrates, what we stand to gain by engaging with it anew is of immeasurable value.

Ntlo E Etsamayang (The Walking House) shows at UJ Art Gallery until Fri, May 17.

Comments