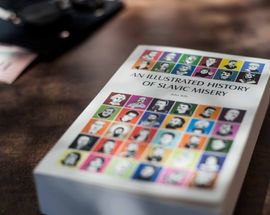

Born in the glorious city of Banja Luka, this stubborn Franciscan chap would go on to be one of the most prominent voices on Bosnia’s emancipation movement of the century. 1818 was the year of his birth, and by the age of 12 he had already been shipped off to the Franciscan monastery in Fojnica where he took on the religious name Franjo.

Franjo’s wanderings would continue through his adolescence. At the age of 17 he headed to Zagreb to study philosophy, and it was here that his future existence as Man of Bosno-Culture (not an official title) would begin to take shape, all thanks to somehow (and I’m assuming this was via internet chat forums) meeting the protagonists of the Illyrian Movement. The Illyrian Movement, if you must know, was a pan-South-Slav cultural and political campaign spearheaded by some young Croatian intellectuals. In some ways it was a pre-cursor to the Yugoslav movement. Slavic cultural revival was all the rage back then, and Franjo was sufficiently enamoured. Franjo’s involvement with them didn’t last too long though, as in 1837, aged 19, he headed to Veszprem in Hungary to study Theology.

The chance meetings continued, as a shady-sounding Bosnian trader called Jovanović presented himself to our hero, and subsequently told him that an uprising was in the works to free Bosnia from the Ottoman yoke. Franjo was pretty excited about this, so in 1840 he took his sweet 22-year-old buns back to Bosnia, only for his religious superiors to tell him that the idea was hopeless and he’d be better off swanning off to Dubrovnik for a couple of years. This he did, before returning to Bosnia in 1842 to travel the country, documenting his vagabonding as he went. After a brief return to Fojnica, Franjo penned a letter that he sent to his Croatian peer Ljudovit Gaj. In the letter, Franjo told Gaj that he planned to establish a new literary society focusing on enlightenment. Unfortunately, this never happened. As in the society never happened, we know the letter part did.

Jukić was a passionate follower of the Illyrian Movement (Ilirski pokret), and it was through this passion and correspondence with other members that he began collecting folk songs in his home nation. By 1844 Jukić’s first volume of Illyrian lyric and epic songs was ready for publication. A collection containing 40 lyric and 10 epic songs, he encountered a number of issues in publishing, not least the fact that the Austrians had begun to clamp down pretty hard on anything Illyrian-related.

When Ivan Franjo Jukić was 30, he moved to Mrkonjić Grad to become a chaplain of a school with around 30 Catholic children and 17 Orthodox kids, making it the first school in Bosnia without religious segregation. Franjo had also spent years collecting cultural treasures, as his addiction to all things Bosnian spiralled out of control. How he collected these things we’ll never know, but one thing we do know is that he was hesitant to collect songs from Muslim singers. He was quoted as saying that ‘the Turks have taken away from the Bosnians everything but their songs’, and the only Muslim songs he included were ‘neutral’ so to speak, omitting anything that glorified an Ottoman victory over a Christian army. Jukić most likely saw the Ottoman Empire with a little trepidation, feeling closer ties to his Catholic brethren in Croatia and Slovenia.

It was in Zagreb that Franjo published the literary journey called ‘Bosanski Prijatelj’ (Bosnian Friend). Only four volumes were published, but its impact shouldn’t be underestimated, as it was the very first Bosnian literary journal and was instrumental in the revival of Bosnian culture with its collection of poems, songs and historical sources. By the way, the reason it was printed in Zagreb is because there was no printing press in Bosnia at the time. I’m no expert, but that would certainly be a fairly steep hurdle to printing a journal.

1851 would see Franjo’s finest hour, but also the same hour that essentially put an end to his practical life in his home nation. In this fine year he wrote ‘Requests and pleas of the Christians in Bosnia and Herzegovina’, continuing the theme of unnecessary long titles. In it, our 33 years young Franjo demanded equality for the Christians of Bosnia, religious and cultural freedom, public schools, freedom of press and more. Basically, he wanted his people to be considered citizens of the Ottoman Empire, not the put upon second-class citizens that they were at the time. Little came of it, but what is notable here is that this was the first European-style constitution to ever be drafted in Bosnia.

It became something of an obsession for Jukić, this re-awakening so to speak of the Bosnians. He wrote poetry himself too, and whilst it was generally of the poorer variety he was more successful simultaneously lamenting and rousing the consciousness of his people, stating that the Bosniaks were seen as a ‘…head detached from the Slavic tree’ and that it was ‘time to awake from a long lasting negligence’. How, I hear you scream? Jukić felt that they needed to ‘try to cleanse our hearts from prejudice, reach for books and magazines’ in an attempt to move ‘our nation of simple people from the darkness of ignorance to the light of truth’. This was all in Bosnian of course, as I don’t think Jukić would try to awaken the national consciousness of his people in English.

Whilst this firmly put Franjo at the head of the Bosnian consciousness, it also led to him being at the head of lists of potential criminals. Jukić was arrested in 1852 after a false accusation from the Ottoman government, and his treatment in prison was less than stellar. He attempted suicide but was unsuccessful, and eventually found himself travelling from Sarajevo to a new prison in Istanbul. On horseback. To put that into some sort of perspective, a bus from Sarajevo to Istanbul in 2016 takes 26 hours. A ride on the back of a horse in 1852? Probably a little longer.

The police ran out of fun however, and eventually Jukić was banished from Bosnia, which was a shame. He took to wandering once again, moving from Istanbul to Rome to Dubrovnik and to Venice, although possibly not in that order. Maybe all this moving adversely changed his health, as in 1856 he fell pretty ill. He headed to Vienna to seek medical help, but unfortunately the only thing he found was death. He died aged 39.

Franjo had managed to cram a lot into those 39 years however, and there weren’t many as dedicated to the Slavic cause as him. His writing pseudonym goes a long way to showing this. His chosen name was Slavoljub Bošnjak, which basically translated as ‘Slavophile Bosniak’. You can’t argue with that. He was of the belief, like many others, that large portions of Bosnia’s Muslim aristocracy at the time were descendants of Christians who accepted Islam in order to protect their property. This idea still exists today, albeit in a slightly more dangerous fashion.

Despite this, Franjo didn’t really give a rat’s arse what your chosen religion was. He publicly advocated a collective Bosnian spirit and tirelessly promoted education and culture in its boundaries. This was especially true with regards to Bosnians Christians, whose culture had been neglected up until this point. Ivan Franjo Jukić can be considered the driving force of the Bosnian national renaissance in the 19th century. He was fiercely nationalistic, although this was in the progressive, liberating sense, not the ‘you aren’t like us so we’ll kill you’ kinda way. His accolades include the first secular school in the country, the first Bosnian literary journal, the first European-style political document and a really cool nom de plume. His collection of national artefacts essentially paved the way for a national museum. Good work Franjo, good work.

Comments